English higher education 2020: The Office for Students annual review

Ensuring high quality teaching and learning

During the pandemic, most universities and colleges that were not already following this model switched to online learning and teaching. Many responded to the initial period of lockdown with considerable ingenuity, running academic and social activities virtually and offering students tailored support to keep them on track.

The pivot to online learning was challenging. Yet it provided greater flexibility for students, and has the potential to be more inclusive if the right infrastructure is in place. This can be particularly valuable for mature students, who are likely to be balancing their studies with caring or work commitments. Many disabled students have welcomed the more widespread use of technologies they have been advocating for some time. During the pandemic, we continued with the National Student Survey (NSS) to ensure that student views continued to be heard.

The transition has not been universally smooth and successful: students’ experiences of the quality of their courses during lockdown have varied significantly.49 The OfS is committed to ensuring that the English higher education system is providing high-quality teaching and learning. We have various mechanisms for ensuring this: baseline regulation through the B conditions, using the TEF to incentivise improvement above the baselines, and the information we publish to inform student choice.

In June 2020, the Secretary of State for Education requested that the chair of the OfS, Sir Michael Barber, conduct a review of digital teaching and learning in the higher education sector in the context of the rapid shift to scaling up online delivery during the pandemic. The Secretary of State asked the review to consider how providers could continue to enhance the quality of online delivery for the next academic year, and to examine longer-term opportunities to develop and innovate in digital and online provision.

We know that high-quality teaching and learning are among the most important things students expect from their degree. In the OfS’s survey of student perception of value for money, 94 per cent said that ‘quality of teaching’ was a very important factor when demonstrating value for money.50 The OfS regulates to ensure that students can be sure their university or college meets minimum quality requirements.

Remote and blended learning

During the early stages of the pandemic, universities and colleges suspended face-to-face teaching and moved to online teaching to limit the spread of the virus. As most higher education providers did not provide significant volumes of remote teaching, much of the early work was aimed at ensuring that teaching could be provided online. This included teaching staff shifting to online lectures and seminars, librarians providing more materials online, and support staff moving to remote support.

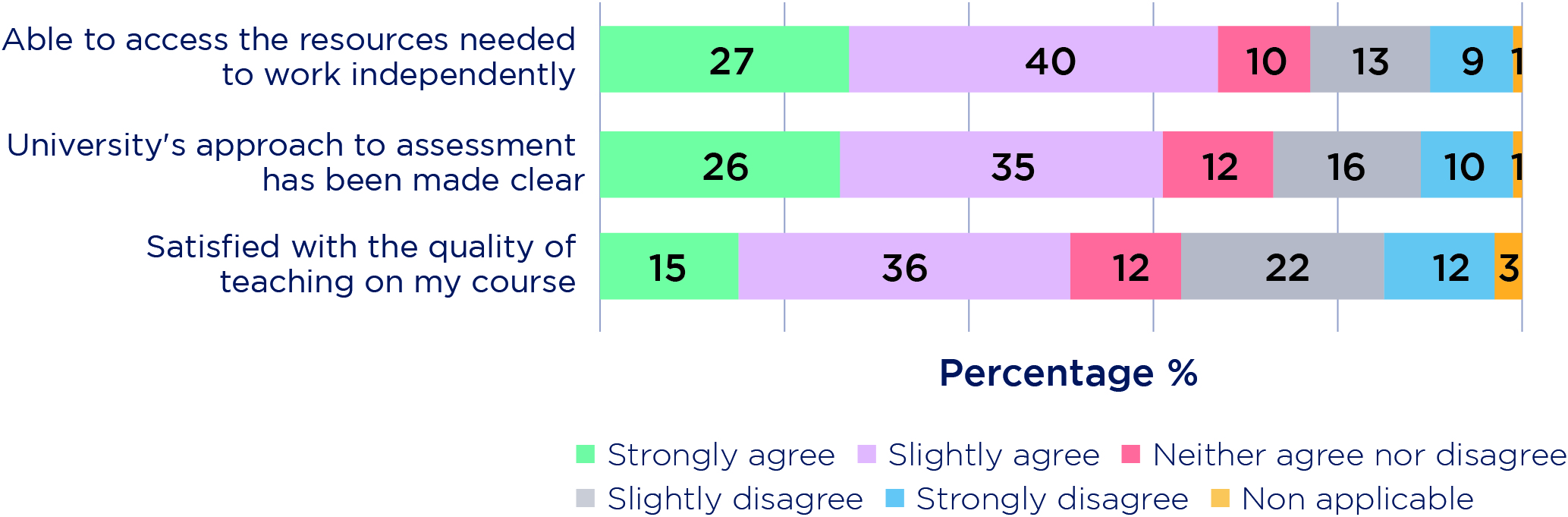

In June 2020, our polling contractor polled 1,416 students for us about the teaching, learning and assessment they had received during lockdown. 51 per cent were satisfied with the quality of this teaching, while 34 per cent were not (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Students' perceptions of course delivery during the coronavirus lockdown51

Figure 1 is a stacked bar chart showing students' perceptions of course delivery during the coronavirus lockdown.

It shows that:

- In response to the statement ‘I have been able to access the resources I need to work independently’, 27 per cent of respondents strongly agreed, 40 per cent slightly agreed, 10 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, 13 per cent slightly disagreed, 9 per cent strongly disagreed, and 1 per cent said it was not applicable.

- In response to the statement ‘The university's approach to assessment has been made clear’, 26 per cent of respondents strongly agreed, 35 per cent slightly agreed, 12 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, 16 per cent slightly disagreed, 10 per cent strongly disagreed, and 1 per cent said it was not applicable.

- In response to the statement ‘I have been satisfied with the quality of teaching on my course’, 15 per cent of respondents strongly agreed, 36 per cent slightly agreed, 12 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, 22 per cent slightly disagreed, 12 per cent strongly disagreed, and 3 per cent said it was not applicable.

A large proportion of students reported their learning was mildly, moderately or severely impacted by technological disruption and lack of study space. Over half of students said their learning was disrupted by slow or unreliable internet. Nearly a fifth said their studies had been negatively affected by lack of access to a computer or tablet. Over half did not have access to good online course materials. More than two-thirds lacked access to a quiet study area. This survey suggests that a significant number of students had their access to remote education disrupted.52

To examine the quality of teaching during the pandemic, the OfS’s chair recently launched a review of digital teaching and learning. The review is examining what worked, and what did not. It will make recommendations for how universities can ensure that the lessons from delivering learning during this period are not lost. The review is ongoing and due to be published in spring 2021.

This academic year, most universities are delivering a system of blended learning, which includes a mix of online and in-person lectures and tutorials. The challenges of this form of learning depend to a certain extent on the course of the pandemic. Local and national lockdowns may mean that providers in those areas may have to do all of their teaching remotely.

Quality and standards

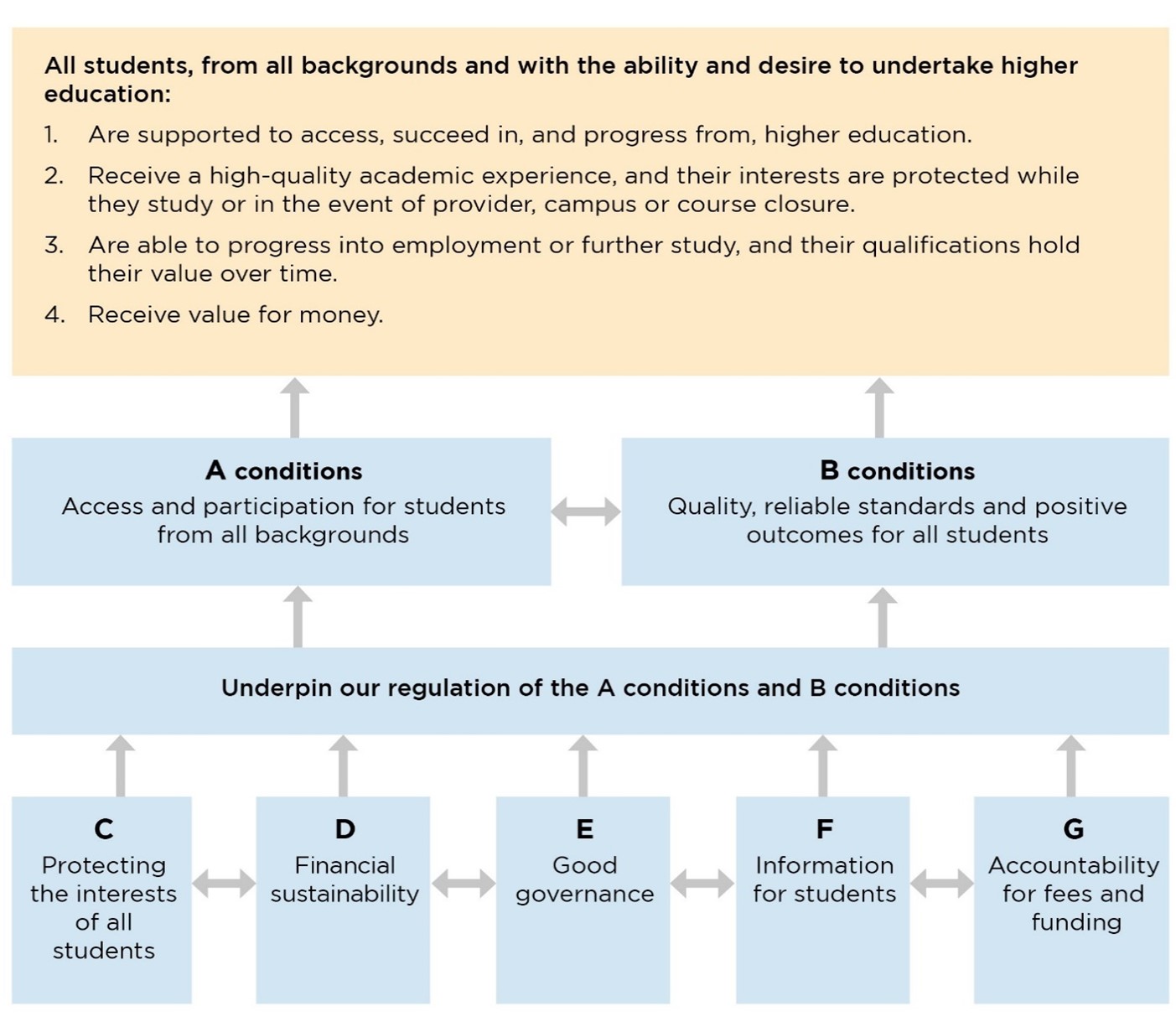

Quality and standards flow through all of our regulatory objectives. This is to ensure that all students, from all backgrounds, with the ability and desire to undertake higher education, receive a high-quality academic experience. In the regulatory framework, we committed to addressing poor-quality provision (see Figure 2). To date, we have refused registration to a number of providers because of concerns about quality.

Since April 2018, we have made assessments of providers seeking registration in relation to the initial B conditions as part of the registration process. We also imposed post-registration requirements on a number of providers because we considered the risk of a future breach of one or more of the B conditions was increased. Subsequently, we have reviewed the action plans produced by these providers and, for some of them, considered the outcomes of reviews by the designated quality body.53 We have also considered cases where our analysis suggests that there is evidence of unexplained grade inflation in the classification of undergraduate degrees.

Figure 2: OfS conditions of registration54

Figure 2 is a flow diagram showing the OfS's regulatory objectives and the conditions that underlie them.

The objectives are as follows.

All students, from all backgrounds, and with the ability and desire to undertake higher education:

- Are supported to access, succeed in, and progress from, higher education.

- Receive a high quality academic experience, and their interests are protected while they study or in the event of provider, campus or course closure.

- Are able to progress into employment or further study, and their qualifications hold their value over time.

- Receive value for money.

Immediately underpinning these, and interacting with one another, are the A and B conditions.

A conditions: Access and participation for students from all backgrounds.

B conditions: Quality, reliable standards and positive outcomes for all students.

Beneath these, underpinning our regulation of the A and B conditions, and again interacting with one another, are the C, D, E, F and G conditions.

C: Protecting the interests of all students.

D: Financial sustainability.

E: Good governance.

F: Information for students.

G: Accountability for fees and funding.

Since April 2018, we have made assessments of providers seeking registration in relation to the initial B conditions as part of the registration process. We also imposed post-registration requirements on a number of providers because we considered the risk of a future breach of one or more of the B conditions was increased. Subsequently, we have reviewed the action plans produced by these providers and, for some of them, considered the outcomes of reviews by the designated quality body. We have also considered cases where our analysis suggests that there is evidence of unexplained grade inflation in the classification of undergraduate degrees.

OfS regulatory work on teaching and learning

The OfS is committed to supporting improved quality of teaching and courses at the providers we have registered. Here, indicators such as continuation, completion and progression to employment or further study are part of our assessment of the outcomes delivered for students. We are consulting on whether our requirements for quality are sufficiently demanding to ensure that all students receive a good education and successful outcomes.

We expect universities and colleges to take all reasonable steps to improve access to higher education for the most disadvantaged, and to narrow the gaps between the outcomes achieved for these students and the most advantaged. All students are entitled to the same minimum level of quality. We do not accept that students from underrepresented groups should be expected to accept lower quality and weaker outcomes than other students. We do not bake their disadvantage into the regulatory system by setting lower minimum requirements for providers that typically recruit these types of students.

We recognise that this presents a challenge for higher education providers: if they are to recruit students from underrepresented groups, they have to commit to supporting these students to succeed. Many universities and colleges deliver on this challenge. However, other providers are not yet meeting this challenge and, while they may provide opportunities for such students to access higher education, too often we see low continuation rates and disappointing levels of progression to professional employment or further study. This is where our regulatory attention needs to focus and we commit more resources to these providers.

Requiring a minimum level of outcomes for students from all backgrounds will remain a central part of our regulatory approach. But we also need to recognise risks to quality and standards that arise from, for example, badly designed or delivered courses, or weakness in academic support, or digital poverty. We are interested in identifying those providers that represent the greatest risk to students – in other words, those that are performing below, or close to, the minimum baseline – and intervening to require improvement. This means that the highest-quality providers, those that deliver successful outcomes for students regardless of their backgrounds, should experience minimal regulatory burden arising from our quality and standards requirements. Conversely, those providers performing below the minimum baseline are likely to experience significant regulatory attention, including the use of the OfS’s enforcement powers.

In November, we launched a consultation that made preliminary policy proposals about the minimum baseline requirements we set for higher education providers, and our approach to ensuring these requirements are met.55 The proposals include:

- Defining quality and standards more clearly for the purpose of setting minimum baseline requirements.

- Defining standards to include new sector-recognised standards for the classifications awarded for undergraduate degrees.

- Expressing some initial conditions that relate to quality and standards differently from equivalent ongoing conditions, to ensure our regulatory approach reflects the context for providers that may not yet have delivered higher education.

- Clarifying the way in which our regulation of quality and standards applies to partnership arrangements and transnational education.

- Setting increased, more challenging, numerical baselines for student outcomes that apply to each indicator and all providers. We have proposed that numerical baselines will not be adjusted to take account of differences in performance between demographic groups.

- Considering a provider’s performance at a more granular level, including performance at subject level, in courses delivered through partnerships, and for students studying outside the UK.

- Improving transparency in relation to the indicators used to regulate student outcomes.

- Clarifying the indicators and other information that we should use to monitor compliance with quality and standards conditions.

- Establishing an appropriate balance between the regulatory burden that intervention places on providers and our ability to regulate effectively in the interests of students.

- Setting out how we would use a range of approaches, including where necessary our investigatory powers, in our engagement with providers to incentivise compliance.

- Indicating how we would use the full range of our enforcement powers when there is a breach of the B conditions, including, in the most serious cases, deregistration.

The consultation is taking place at an early stage of our policy development. We expect to consult again on more detailed proposals early in 2021.

National Student Survey

The NSS is an annual survey that captures students’ views on their courses. More than 300,000 students respond each year; in 2020, it had a response rate of 69 per cent.56 In gathering students’ perceptions about key aspects of the academic experience, NSS data has three main objectives: providing information for prospective students to help them understand how well different courses are run; supplying universities and colleges with data to improve their students’ experience; and supporting public accountability. The NSS provides insights at a sector level through course-, subject- and provider-level results, including through TEF metrics. The survey shows considerable variation between providers. For example, in responses to Question 15, ‘The course is well organised and running smoothly’, there is a 29 percentage point difference between the bottom 10 per cent of providers (where 49 per cent or fewer of students agree) and those in the top 10 per cent (where 78 per cent or more of students agree).57 This shows that while most students are happy with how their courses are run, there remains room for improving organisation at some providers.

The OfS is currently reviewing the NSS following a request by the Universities Minister to investigate concerns that the survey creates too much burden for providers and is driving down standards. The first stage of the review is exploring the unintended and unanticipated consequences of the NSS on providers’ behaviour, including whether it drives the lowering of academic standards and grade inflation, and how this could be prevented. It is also examining the question of burden: the appropriate level at which the NSS could continue to provide reliable data on students’ perspective on their subjects, providers and the wider system, and whether a universal annual sample is necessary. The second stage will look more widely at the role of the NSS, including which questions should be asked to support regulation and student information across all four countries of the UK. We sought to gain the views of a range of stakeholders including students at different stages of their studies; those in leadership and academic roles within universities, colleges and other providers; sector stakeholder groups; publishers of student information; and others with an interest in the results. We have worked closely with students, through multiple student workshops including a joint one with the National Union of Students, and we have also run a representative poll with students and a survey of students’ unions. Members of the student panel have also been closely involved with the review. We expect to have completed the review by the end of 2021.

Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework

The OfS incentivises excellence in teaching and outcomes beyond the minimum regulatory baseline through the TEF. The current TEF looks at the learning environment and the educational and professional outcomes achieved by students, as well as the quality of teaching, and has demonstrated its value in focusing attention on these issues across the higher education sector.

We expect to consult on our future approach to the TEF after the government has published Dame Shirley Pearce’s independent review of the TEF,58 and its response. Our proposals for this future consultation will likely be informed by these publications, and by findings from the OfS’s subject-level TEF pilots.59

We want to build on progress made through the TEF to date and develop a new version of the exercise that will further incentivise teaching excellence among universities and colleges. We want to ensure that this new version works in the best interests of students without unduly burdening providers. Our intention is to ensure that our approach to regulating the minimum baselines contained in the B conditions and the above-baseline assessment undertaken for the TEF combine to produce a coherent overall approach to quality that delivers our regulatory objectives.60

Student protection and market exit

The pandemic and the consequent government restrictions meant that (in most cases) higher education providers needed to make rapid and significant changes to the ways they delivered teaching and assessment. At the same time, all universities and colleges were expected to continue to comply with consumer protection law and to uphold their contracts with students. Recognising the difficulties of delivering courses and assessments in the same way, in June we issued guidance to providers setting out our expectations that they should give all their students clear, accessible and transparent information about what they could expect.61

Students are consumers, and consumer protection law continued to apply throughout the disruption caused by the pandemic. It was important for providers to ensure that their terms and conditions remained fair and transparent, and that students had continued access to accessible, clear and fair complaints processes. We published student and consumer protection guidance to address this issue, emphasising that universities and colleges needed to ensure that prospective students should have clear and timely information about how their courses would be delivered, and existing students should be provided with information about any adjustments to their courses and assessment.62

Students have faced significant disruption. Some caught coronavirus; others needed to self-isolate; many were unable to move from their term-time accommodation, or were less able to access and effectively participate in remote learning. Our guidance emphasised the importance of considering how providers’ approaches to the situation affected all students, particularly those who might be most vulnerable to disruption.

Given the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on higher education providers, we announced in March 2020 that we were pausing planned consultations.

Exceptions to this rule were our consultations on the stability of the sector and student protection issues, bearing in mind the potential risk to students of the market exit of a provider. We therefore launched a consultation in July 2020 that focused on student protection issues that might arise where there is a material risk of market exit. Following a consultation, we made a decision to amend the regulatory framework so that providers would be required to comply with ‘student protection directions’ issued by the OfS as a result of a new general ongoing condition of registration.

Degree value

One of our roles is to ensure that qualifications hold their value over time. In simple terms, a first-class degree awarded now should represent broadly the same level of student achievement as one awarded in five or 10 years’ time.

In 2018-19, 29.1 per cent of students were awarded a first. This represents only a slight increase from 2017-18 when 28.9 per cent of students received a first, and a substantial slowing-down of the previous year-on-year increase.63

In 2019-2020, there could well be another increase in the number of firsts, as many providers adopted more flexible approaches to assessment arrangements because of the pandemic. For example, some providers operated a range of ‘no detriment’ policies to ensure that students were not unfairly penalised by the disruption during the spring and early summer.

2021 priorities

The uncertainty relating to the delivery of teaching during this academic year means that our work as a regulator is more important than ever. To ensure that universities and colleges continue to provide quality teaching and learning, during the coming year we will:

- Conclude our online teaching and learning review.

- Publish the findings of our consultation on quality.

- Consult on our future approach to the TEF.

- Conclude our review of the NSS, and publish the findings.

49 OfS, ‘“Digital poverty” risks leaving students behind’, September 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/digital-poverty-risks-leaving-students-behind/).

50 Trendence UK, ‘Value for money: The student perspective’, March 2018 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/new-research-shines-spotlight-on-student-perceptions-of-value-for-money/), p16.

51 The responses collected have been weighted to correct for the under- and overrepresentation of some student groups. See OfS, ‘“Digital poverty” risks leaving students behind’, September 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/digital-poverty-risks-leaving-students-behind/).

52 The responses collected have been weighted to correct for the under- and overrepresentation of some student groups. See OfS, ‘“Digital poverty” risks leaving students behind’, September 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/digital-poverty-risks-leaving-students-behind/).

53 This provides a simple visual representation of the relationships between the areas we regulate through different groups of conditions. It does not represent a hierarchy in which compliance with some conditions is more important than compliance with others. All providers are required to comply with all applicable conditions of registration as set out in the regulatory framework.

54 UK Government, ‘Higher Education and Research Act 2017’, (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/29/section/23/enacted), section 23.

55 OfS, ‘Executive summary: Consultation on regulating quality and standards’, November 2020 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/consultation-on-regulating-quality-and-standards-in-higher-education/), p2.

56 OfS, ‘National Student Survey – NSS’, October 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/get-the-nss-data/). OfS analysis showed that the results had not been strongly impacted by the pandemic. OfS, ‘National Student Survey 2020: Analysis of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic’, July 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/nss-2020-analysis-of-impact-of-coronavirus/).

57 OfS, ‘National Student Survey – NSS’, October 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/get-the-nss-data/).

58 UK Government, ‘Teaching excellence framework: Independent review’ (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/teaching-excellence-framework-independent-review).

59 OfS, ‘Subject-level pilots’, July 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/teaching/future-of-the-tef/subject-level-pilots/).

60 This is set out in further detail in Annex D of our consultation on regulating quality and standards in higher education. OfS, ‘Consultation on regulating quality and standards in higher education’, November 2020 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/consultation-on-regulating-quality-and-standards-in-higher-education/), pp54-55.

61 OfS, ‘Guidance for providers about student and consumer protection during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic’, June 2020 (available at https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/guidance-for-providers-about-student-and-consumer-protection-during-the-pandemic/).

62 OfS, ‘Student and consumer protection’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/coronavirus/provider-guide-to-coronavirus/student-and-consumer-protection/).

63 OfS, ‘Official statistic: Key performance measure 18’, November 2020 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/measures-of-our-success/outcomes-performance-measures/students-achieving-1sts/).

Describe your experience of using this website