In a personal reflection, the OfS’s Director for Fair Access and Participation, Chris Millward, looks back across two decades of policy, funding and regulation – and forward, as the next chapter unfolds.

This is an abridged and edited version of a speech given at the Centre for Global Higher Education on 11 May 2021. The full version has been published by the Centre.

This is a story in five parts, reflecting the changes to funding and regulation across the period, punctuated by independent reviews, white papers and legislation.

- In the first part of the century, government grant to universities and a small student contribution helps to finance widening participation by increasing places, then is given momentum by the commitment to a 50% participation rate for young people.

- In the second part, there is an increase to the contribution made by graduates from 2006, albeit through income-contingent loans, together with a more activist approach to reaching underrepresented people and places, and a fair access regulator to avoid them being disadvantaged

- The third part, following the global banking crash and a change of government, sees more radical cost sharing with graduates from 2012, together with the strengthening of measures to support the most disadvantaged students, and to empower student choice and demand.

- In the fourth part, legislation in 2017 establishes the architecture for a student-led system. This signals a decisive change, from oversight by a funding body (HEFCE) to a regulator – the Office for Students – tasked with acting in the interests of students, and making fair access and participation a priority.

- And now, the fifth part: a potential shift in the consensus that has governed policy towards increasing participation in higher education during the century to date, with a focus on levelling up opportunities, whichever route is followed through post-compulsory education.

There are also the five features you should find in any good story:

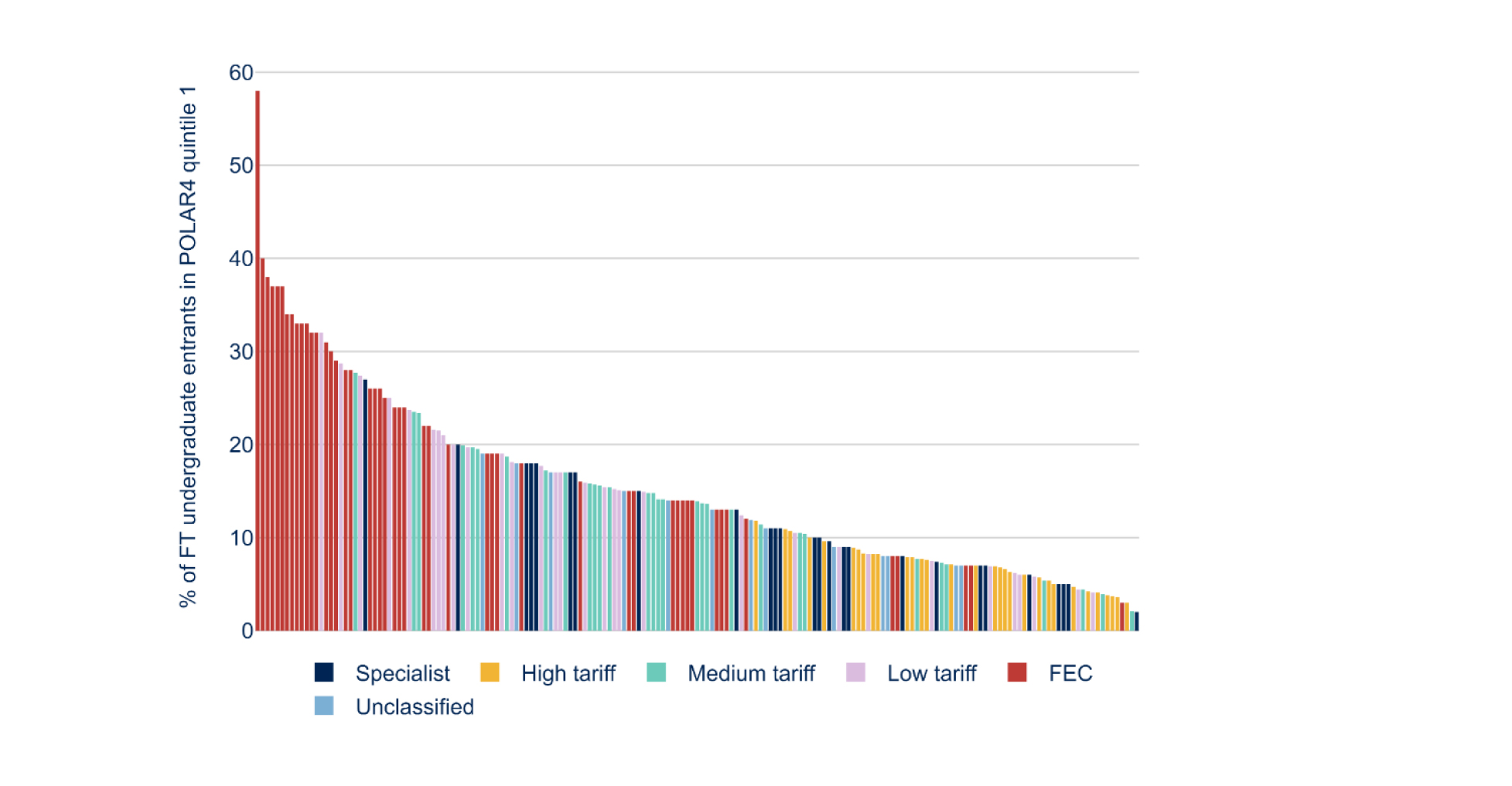

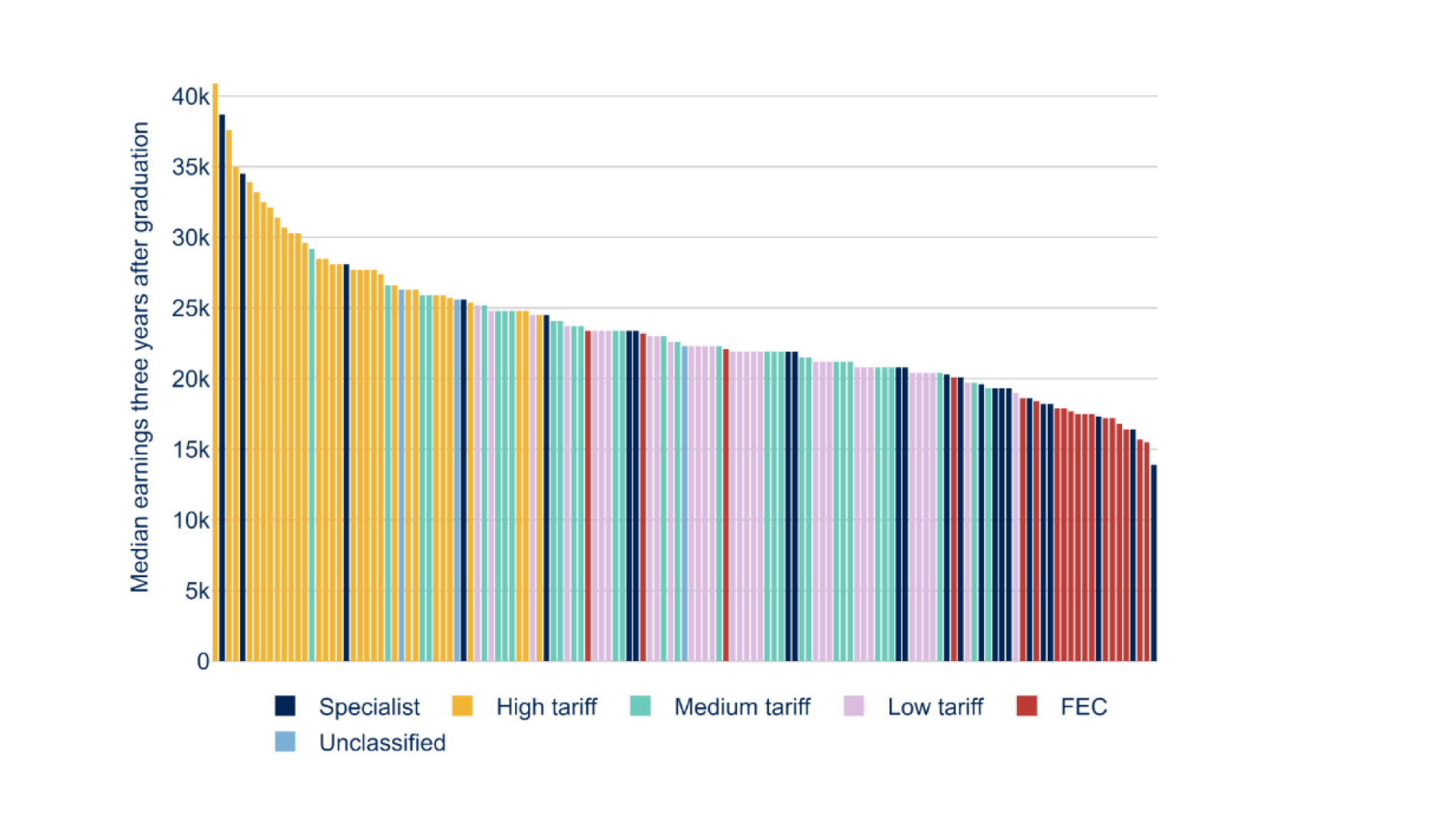

Setting – the English higher education system, fixed in the minds of the nation and the world around our ancient collegiate universities, which still channel much of our elite. Despite expansion and diversification, to the extent that more than half of current graduates now study and work where they grow up, university in England is still widely perceived as residential, academic and elite, indeed this is part of its global appeal. The young, full-time, full-degree model continues to dominate. The system is also highly stratified, with the most prestigious and research-intensive universities, which lead to the most highly paid and prestigious jobs, recruiting the lowest proportions of disadvantaged students, as shown in figures 1 and 2 below.

This itself reflects a particularly strong relationship between social background and school grades, and school grades and university admissions – an ‘efficient sorting system’ as one researcher told me. A key related factor here is place: the very low levels of higher education participation in post-industrial towns across the north and midlands, and coastal towns.

The government’s levelling up agenda provides the wider social, political and economic backdrop to this setting. It has come into even sharper focus during the coronavirus pandemic, which has hit the poorest people and communities hardest.

Figure 1 – Institutional distribution of students from low participation neighbourhoods

Figure 2 – Institutional distribution of median earnings three years after leaving a degree course

Character – politicians, vice chancellors, student unions and review bodies have all shaped the debate around the changes I am describing. But the most important characters for me are students and their families, who have increasingly aspired to go to university and get a degree, despite the increasing cost to them over time, indeed the most prosperous families and schools have done all they can to sustain their hold over the most selective universities and courses. Alongside this, people who have not been to university have become increasingly influential through the ballot box.

Conflict – between students, universities and government over fee levels, and between the identity and values of graduates and non-graduates, and the places where they tend to live.

Plot – the pursuit of increasing higher education participation in the belief that it would create a more fair and open society, an education-based meritocracy enabling social mobility, and thereby life chances to be determined by ability rather than background.

Theme – that in liberal societies like England, within which there is choice for students and families within the education system, higher education expansion will not reduce inequality and perceptions of fairness on its own. Other measures are needed to equalise opportunities, both in and beyond higher education. These measures need to bridge the divisions between higher and further education, academic and vocational education, graduates and the wider population, and the places where they live.

The next chapter…..

Earlier this week, the Queen’s Speech confirmed the government’s intention to introduce a Skills and Post-16 Education Bill as the legislative underpinning for the reforms set out in the ‘Skills for jobs’ white paper. The reforms envisage radical change to the way post-compulsory education is financed, with the aim of levelling up the incentives between further and higher education.

In order to succeed, this vision will need to meet the aspirations of young people and their families, the recruitment patterns of employers, and the needs of future jobs. It will need also to avoid entrenching the divisions between academic and vocational routes, which tend to follow attainment in school and thereby social background.

That means universities must be central to the vision, working with further education colleges and bridging between academic and vocational education, not just the route that is discouraged. If universities bring their subject expertise, their relationships with businesses and public services, and their global partnerships, students will want to take these routes and employers will want to employ them. This should enable everyone, when they are ready and they want it, to stretch their learning as far as they can.

Comments

Report this comment

Are you sure you wish to report this comment?