Susan Lapworth, the OfS’s chief executive, argues that focusing quality assessment on core academic matters means focusing on the things that matter to students.

This is an edited transcript of a speech given on 2 December 2022 by Susan Lapworth at a Universities UK members’ event.

As you know, I was recently appointed as the OfS's chief executive. At my interview I was asked the sort of questions that any interview panel would ask. So, of course, they asked why I wanted the job. That gave me pause. But my answer was that this job brings two things together for me:

I care about the higher education sector. And I enjoy being a regulator.

Our sector is important for the country and for individuals – it's a combination of public and private good. It was certainly important for me and the way my life has turned out. I wouldn't be here if I hadn't been the first in my family to go to university. I also worked in higher education institutions for many years and enjoyed that hugely. Universities and colleges are full of interesting, smart people doing important work.

But it's clear that things don't always work as they should for students. And it's hard to make change happen from within, even in the most senior jobs in an institution. I found that frustrating. So I moved to a role where I could think about the whole sector.

There's a satisfying intellectual challenge in thinking about a diverse and complex sector and debating regulatory strategy and tactics. But more importantly, this role gives me a voice to shape the sector in the interests of students and society, for the long term. I think that's what you're all trying to do too. I see that as a shared endeavour.

But my fondness for the sector doesn't mean that I can't see how it might need to change and adapt. The OfS's new strategy focuses our work for the next few years on pushing further on equality of opportunity for students who may not have had the same opportunities that I did. And on quality – the thing that matters most to students while they're studying.

I want to pick up that second theme today and talk more about quality. We're increasingly active in this area. New regulatory requirements are now in place, and earlier this year we began a first set of investigations into business and management courses – I want to describe the approach we are taking to those particular investigations. More changes in the landscape are due in the next few months as the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) steps away from its role as the designated body.

There's been lots of commentary on these various issues, not all of it well informed. I also want to put some of that straight.

The OfS quality team

I want to start by introducing some of the core team leading on quality at the OfS:

- Dr Isabel Hopwood is an education practitioner and academic developer with twenty years' experience, most recently at the University of Bristol. Her post-doctoral research interests include assessment and feedback practices in higher education.

- Professor Graeme Pedlingham is on loan to us from the University of Sussex, where he is the university's Deputy Pro Vice-Chancellor (Student Experience). He has a particular interest in student transitions and approaches to academic support.

We expect to welcome in the new year a further professorial colleague with extensive experience in senior academic posts in the UK and internationally.

The team is led by Dr Nick Holland, who has published research on renaissance philosophy which is fascinating – although perhaps less directly relevant to regulating quality! – alongside his career as an academic registrar and head of an institution – so he has experience of being on the receiving end of OfS regulation.

Others in the team have extensive experience of working in institutions, or in sector bodies such as the Office of the Independent Adjudicator, the QAA or the OfS's predecessor, the Higher Education Funding Council for England.

You would expect me to say that my colleagues are excellent. But there are two important points here:

First, this is not an inexperienced team.

Second, this is a team built around academic expertise.

An academic turn

This underlines the change we're making in how quality is assessed. The requirements in our 'B' conditions include how university curricula are designed and delivered, the academic support that particular cohorts of students need, and whether assessment is rigorous in practice. Those are all matters of academic concern. They cannot be properly understood by looking at paper trails through an institution's quality assurance processes.

That's why we also have a panel of expert academic assessors to give us independent judgements about a particular higher education provider as part of these investigations. We have recruited people able to reach robust academic judgements focused on the learning, teaching and assessment provided for students, rather than on the processes an institution follows to deliver those things.

The focus of our current investigations is therefore on academic rather than administrative matters – an 'academic turn' in quality assessment. That turn feels right to me and we shouldn't underestimate its importance.

It's something I feel strongly about because of my own experience of working in the sector. I've led quality teams well-versed in taking external expectations – the Quality Code, subject benchmark statements and so on – and turning them into systems and processes to apply across the whole institution. But those systems and processes often felt as though they were getting in the way of the ability of academic departments to shape their approaches within a particular disciplinary context and to meet the needs of their students. They also seemed to tangle academic colleagues up in red tape.

This photo, from a Guardian article in 2001 shows five economics professors from the University of Warwick making a reasonable point about the volume of paper they had generated for a subject review visit. Things have obviously moved on a lot since then – but the point bears repeating, not least because new providers have told us that this is still their experience of review visits, and that they don't think it adds value.

Pulling the focus squarely back to learning, teaching and assessment brings huge opportunities to look again at whether those complex assurance processes within institutions are needed. I can see that a new, inexperienced provider might find it helpful to have the scaffolding provided by the Quality Code. But I'd challenge more established institutions to think again about whether they need all of that internal burden.

And, of course, focusing on learning, teaching and assessment means we're all focusing on the things that matter to students and other stakeholders.

Independence

Some of those stakeholders are politicians. The OfS undertakes all its regulatory work independently of government, and does so rigorously. But there is a political backdrop to our work, including on quality, that none of us can ignore.

For example, ministers may be concerned that a peer review system means that the sector continues to 'mark its own homework'. We don't have a national curriculum, or an exams regulator, in higher education. None of us would think that was a good idea – institutions' autonomy to decide what and how they teach and assess is too important for that.

That's why we've been working with our team of academic experts to help them locate their academic judgement in our regulatory context and to take the opportunity to reset the norms for their discipline where they think that's appropriate. We're building an approach to assessment that looks credible, even to the sceptics.

Our assessors are determining their lines of enquiry and the evidence they want to look at. They'll reach their own judgements and write their own reports. Their independence is real: the people we've recruited are not the sort to toe any particular political line.

We also have an important committee – our Quality Assessment Committee – which has the statutory role of giving advice on quality assessment matters. The majority of its members are independent and they must, and do, have experience of providing higher education to students.

In short, independence flows through these current investigations – and it comes from the independent judgements of academic experts. That's more important, in my view, than focusing on which organisation – the OfS or a designated body – is making practical arrangements for the assessment visits to providers. We're concerned with academic independence, rather than simply administrative independence.

The OfS quality system

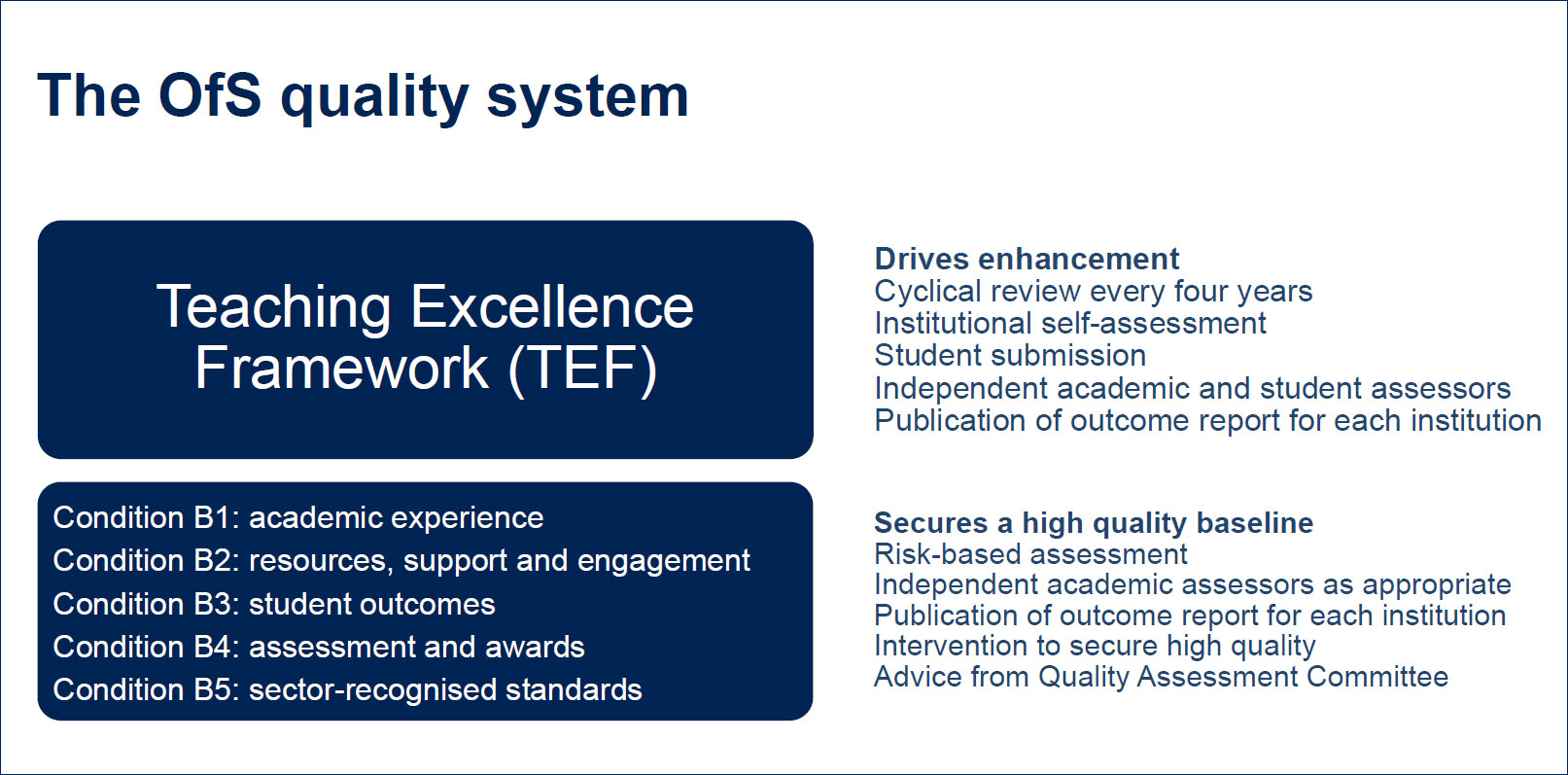

Finally, I'm going to give a quick overview of the quality system in England as a whole, and how the pieces fit together.

The bottom box in the diagram shows the B conditions of registration. These are designed to secure a high quality baseline of performance for all providers. The emphasis is on high quality – this is not a lowest common denominator baseline. It ensures that all students – from the UK and overseas – can expect a high quality course and successful outcomes wherever they choose to study. Many institutions sit comfortably above that high quality baseline: we operate a risk-based system to identify areas and institutions where further scrutiny might be appropriate. Being risk-based here is an active philosophical choice as well as a statutory requirement.

Above the high quality baseline is the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). In England, this is the mechanism we use to drive improvement, or enhancement, beyond the high quality baseline. The TEF is a cyclical process – we expect to run it every four years. Institutions make a submission, as do their students if they wish. Judgements are made by academic experts, with students integrated as full members of the TEF panel. We expect to publish, for each participating provider, the panel's judgement and reasoning.

In sum, looking at this system as a whole, in England:

- we have a cyclical enhancement mechanism

- we expect to publish assessment reports for individual institutions

- we draw on independent academic judgements

- students are fully involved as equal partners in making judgements about quality.

These aspects have featured in recent debates about European quality expectations. Our view is that the quality system, as a whole, in England is consistent with those expectations. It is credible and rigorous. We should not allow regulation in this area to be presented as an inadequate low quality set of expectations – because universities and colleges are well-regulated. It's in the interests of students, the general public and the sector that our regulation is of high quality and is well regarded in the UK and internationally.

Comments

Report this comment

Are you sure you wish to report this comment?