Chris Millward reflects on the content of his keynote presentation at the Advance HE Governance Conference: Evolving governance fit for our futures on 18 November.

Many of the most enlightening insights during my time as Director for Fair Access and Participation have come from meetings I have had with the students supported by access and participation plans agreed with the OfS. These students, who are usually the first in their family to go to university, can have a powerful influence within universities, raising the ambitions of senior leadership and governors, and holding them to account.

They demonstrate the importance of diversity to the learning experience in higher education – how a healthy and vibrant educational environment brings different identities, perspectives and backgrounds together. They also remind us how much further some students have to travel to get into university, the resilience that is needed for them to succeed whilst they are there, and the further barriers they can face at the next frontier, whether it is the graduate jobs market or postgraduate education.

This is exemplified by the pattern of differential outcomes we see in relation to race and ethnicity in higher education.

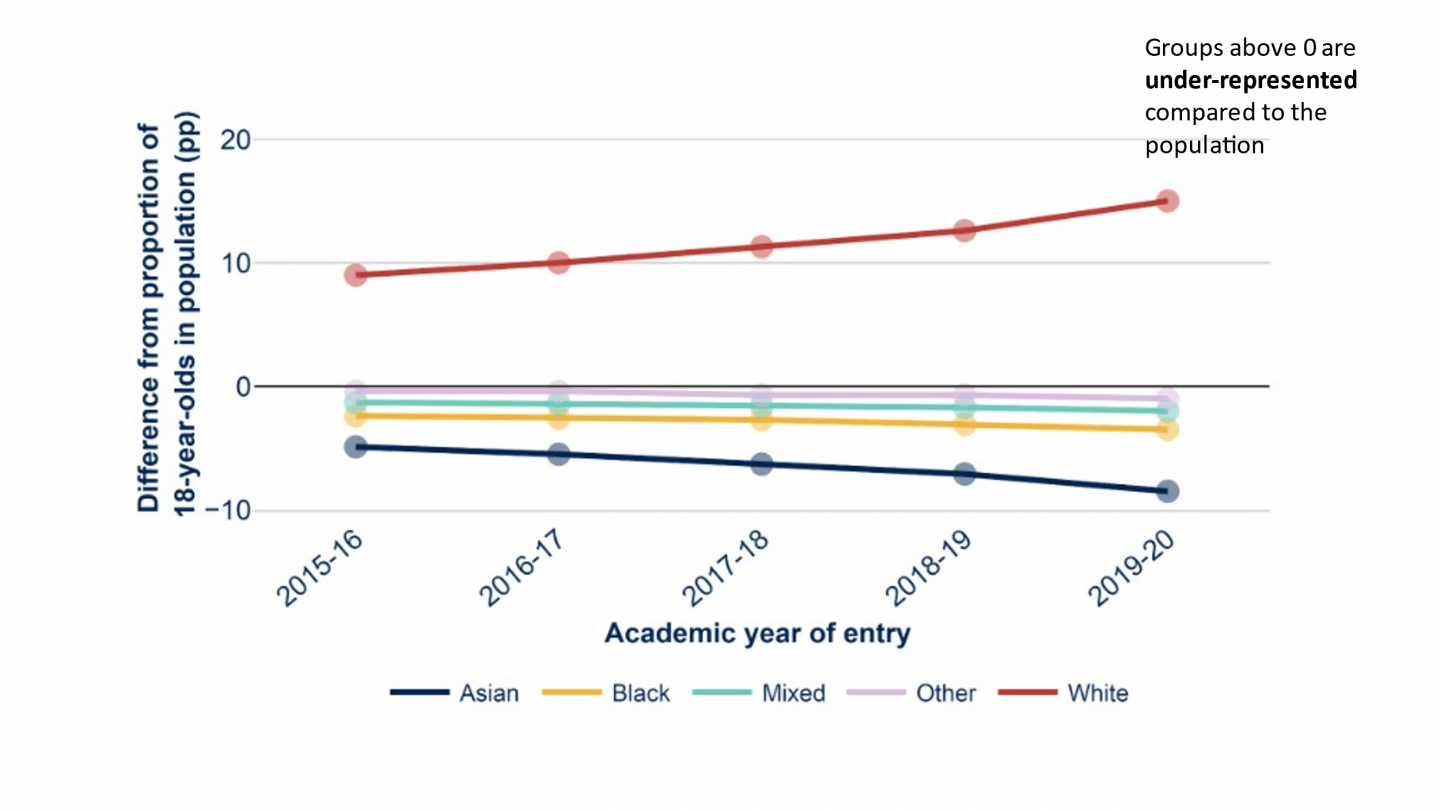

Figure 1 below shows that higher education participation for Black, Asian and minority ethnic students is higher than their representation in the wider population.

Figure 1 – Gaps in the proportion of 18 year olds entering higher education compared with the wider population

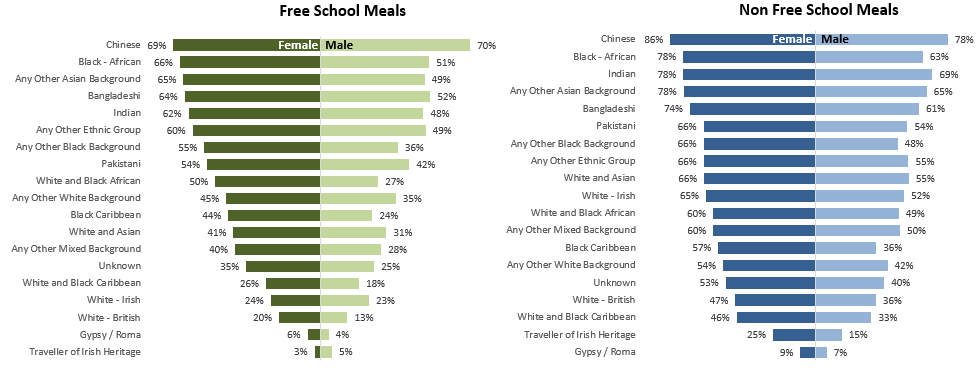

These patterns reflect the ethnic diversity of London and other cities where there are high levels of higher education participation, and they reflect the excellent work by schools, colleges and universities in these communities. They are apparent also for many of the most disadvantaged students, for example those who have been eligible for free school meals, as demonstrated in Figure 2 below. The progression rates for Black African, Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani students who have been eligible for free school meals are all high overall, and much higher than the rates for White British students.

Figure 2 – Progression to higher education by age 19 by ethnicity, gender and free school meal status

I hope we will now see the same progress in communities that have been left behind as higher education has expanded, which are mostly in post-industrial towns and parts of cities across the north and midlands, and coastal towns.

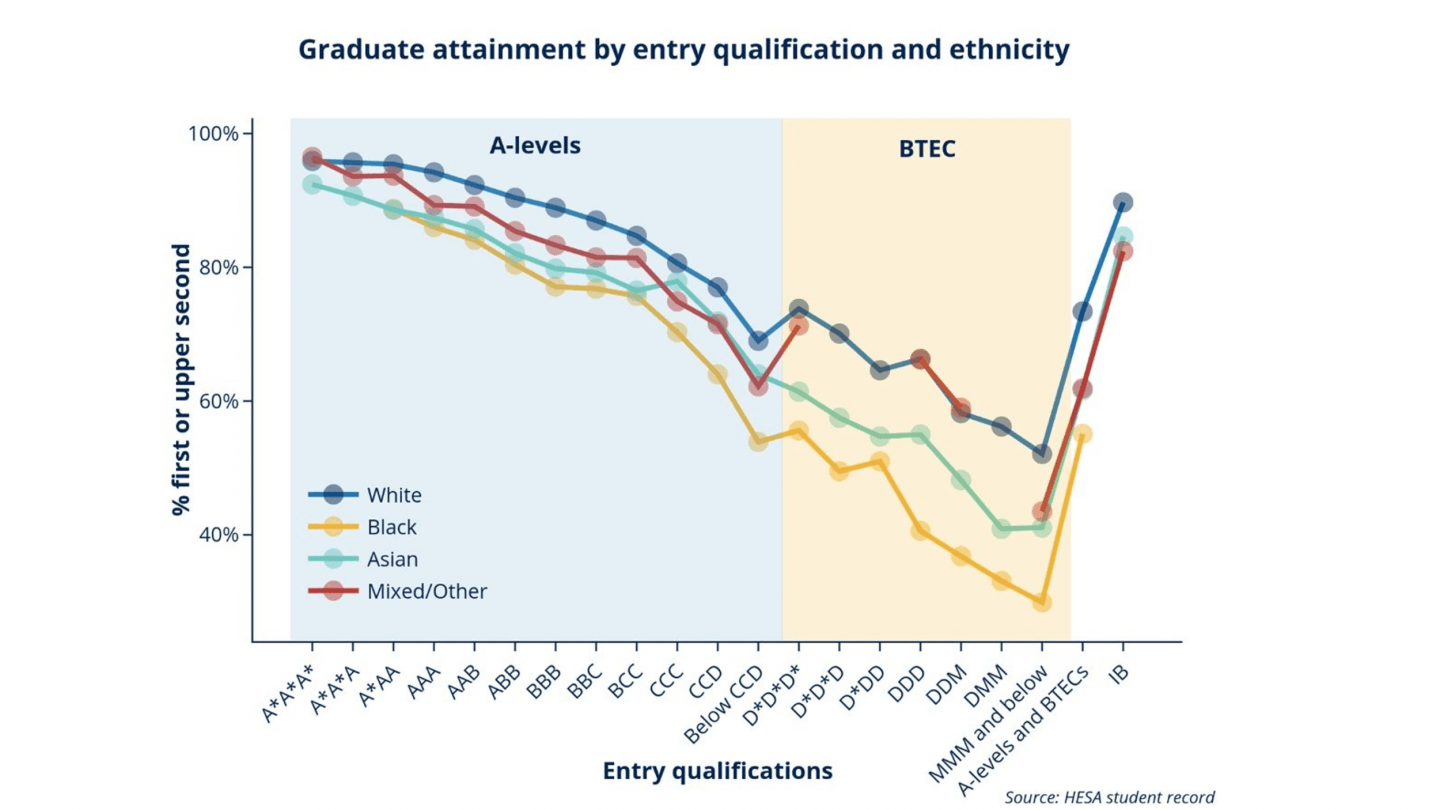

Although Black, Asian and minority ethnic students have higher rates of participation in higher education, they have lower success rates once they get there. This is most strikingly the case for the proportion of students achieving 1st or 2:1 grades, as demonstrated by Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – Proportion of students achieving first or upper second grades by entry qualification

Crucially, this is consistent across nearly all entry grades. It also, in my experience, applies across all types of universities and colleges, as is clear from the self-assessments you can see within their access and participation plans for 2020-21 onwards.

Universities and colleges have been aware of these patterns for many years, but there has been an element of distraction by data – a focus on analysing the numbers, rather than identifying the causes and the actions needed to address them.

Having published a number of reports doing exactly this, we decided during my time at HEFCE to commission a relatively simple typology of the causes of differential outcomes. This identified issues relating to: the curriculum and learning; teaching and assessment practices; relationships between staff and students, and between students; differences in how students experience higher education, how they network and draw on external support depending on their social, cultural and economic capital; and ultimately the extent to which different students feel supported and encouraged in their daily interactions - above all, whether they feel they belong.

More recent studies by the equalities regulator and universities' own representative body have been more challenging, highlighting incidents of racism on campus, a culture of ignorance and complacency, and ultimately a systemic failure to create the environment all students deserve.

Tackling this is not easy. It requires honest self-reflection and uncomfortable conversations with colleagues. It demands scrutiny and debate about core tenets of academic life, such as the nature of the curriculum, the conduct of learning and the approach to assessment, all of which can invite public criticism. It calls for universities and colleges to change established ways of working so they embrace the full diversity of their student population, rather than expecting students to change themselves.

These are the kinds of activities universities committed to deliver through the access and participation plans agreed with OfS in 2019 – publishing honest self-assessments, engaging with staff and students to understand the causes of their ethnicity awarding gaps, setting goals to reduce them and interventions to achieve this, and evaluating whether they work.

Students, for the first time, appeared to believe that progress was being made, as is clear from the statement made by the then Vice President of NUS in his foreword to the Closing the Gap report of 2019.

‘My fear on starting this process was that it would stir up some interesting conversations, articles and commentary, but ultimately have no long-lasting impact for BAME students. However, some key things have changed in relation to the BAME attainment gap. The sector now accepts that there is a problem – many more students’ unions are aware that there is an issue and have prioritised it in their campaign work; the Office for Students (OfS) in England has set new targets for institutions to close their gaps and the issue has even been given a profile by the Cabinet Office and the government’s Race Disparity Audit.’

This describes a powerful alliance against race and ethnic disparities in higher education: universities working with students, with pressure and support from the higher education regulator and the government. Simon Woolley and his colleagues working in Downing Street at that time were particularly influential, pushing all of us not just to talk about race and ethnic disparities, but to take action to address them and set measurable goals for improvement.

Two years on from the agreement of these plans, it is interesting to reflect on how discussions about race and ethnic disparities have moved on, enlightened by the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 and the response to them by students, universities and the government.

I still see leaders throughout public life saying they want to reduce race and ethnic disparities, indeed this has become a higher priority for many organisations since the Black Lives Matter protests. But the measures that are used to tackle these disparities appear to have become more contested. There is a view, for example, that individuals should take responsibility for their own destinations, so this should not be undermined by actions to advance them, least of all by positioning them within groups based on their race or ethnicity.

This, though, ignores the entrenched character of the disparities we see once students reach higher education, and the extent to which relying on opportunity for individuals has yielded no action or progress at all.

The implications of getting a first or 2:1 extend well beyond undergraduate education. This can be important for graduates to be able to compete for jobs and for progression onto postgraduate research. Research programmes are, of course, the route into academic careers, and thereby the staffing of universities themselves, so there is a loop back to the patterns at undergraduate level.

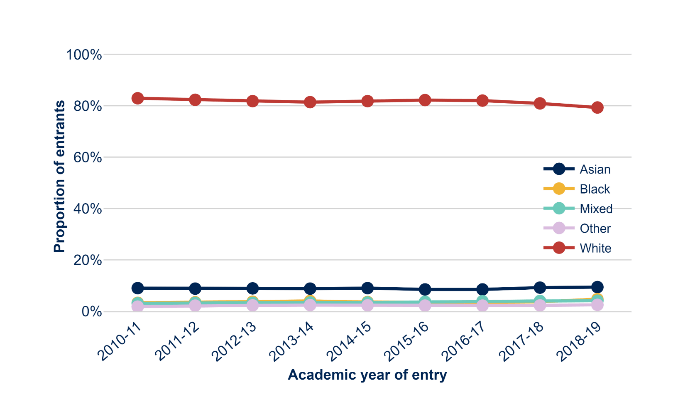

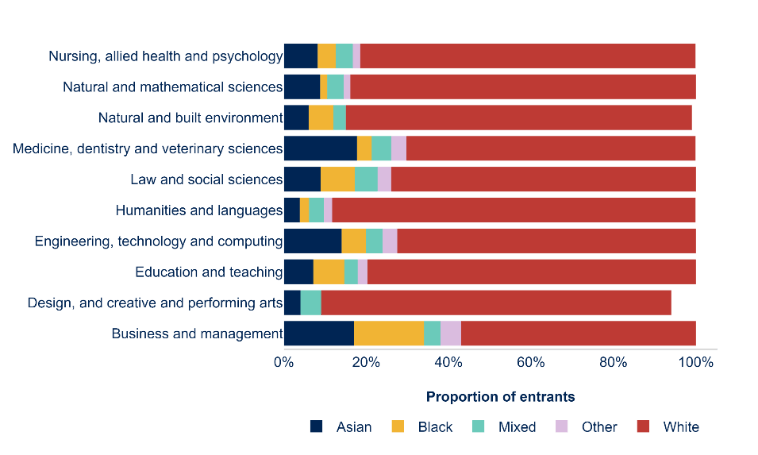

This is clear from the charts in Figure 4 below, which demonstrate the slow rate of change to the pattern of postgraduate research entrants, especially given the changing profile of the undergraduate population. Note particularly the low proportions of Black students in STEM subjects, which has been identified as a concern by the Royal Society.

Figure 4 – Entrants to postgraduate research courses

With this in mind, OfS is building on the commitments made at undergraduate level through access and participation plans by tackling, with our colleagues in Research England and UKRI, this next frontier. Earlier this week, the government confirmed the projects to be funded from an £8m programme, through which universities will work collaboratively with each other to bridge the gap between undergraduate and postgraduate education for Black, Asian and minority ethnic students, piloting changes to admissions within universities and disciplines, and creating new pathways through doctoral education and research careers.

I hope the announcement of this programme will renew the momentum for action to address race and ethnic disparities in higher education: that universities and colleges will face up to the real barriers faced by their own students - and not just by talking about the problem, analysing the data, or indeed putting the onus on individuals to change. Diagnosis of the problem demands prescription of the cure – this requires positive action.

This blog post was originally published on 25 November 2021 on the Advance HE website.

Comments

Report this comment

Are you sure you wish to report this comment?