The Office for Students (OfS) is working with universities and employers so that improvements to access in higher education lead to opportunities in the workplace.

The first OfS regulatory objective, agreed at our first board meeting in January 2018, is that all students from all backgrounds with the ability and desire should be supported to access, succeed in and progress from higher education.

This serves individual students, who want to benefit from the experiences and opportunities that flow from higher education, but also local and national businesses and public services who rely on the highest levels of knowledge and skills.

As the regulator of universities and colleges in England, the OfS has the most direct influence on the success element of our first regulatory objective – in other words what happens to students whilst they are in higher education. This is crucially affected by factors we regulate such as governance, student protection and above all the quality and standards of courses.

Whether and where you go to university, and what you do once you have left, are inevitably affected by factors beyond higher education. Patterns of access are affected by school grades and graduate employment by conditions in the labour market. Both tend to reflect wider inequalities, which seem likely to have been compounded by the pandemic, and within which location is particularly influential.

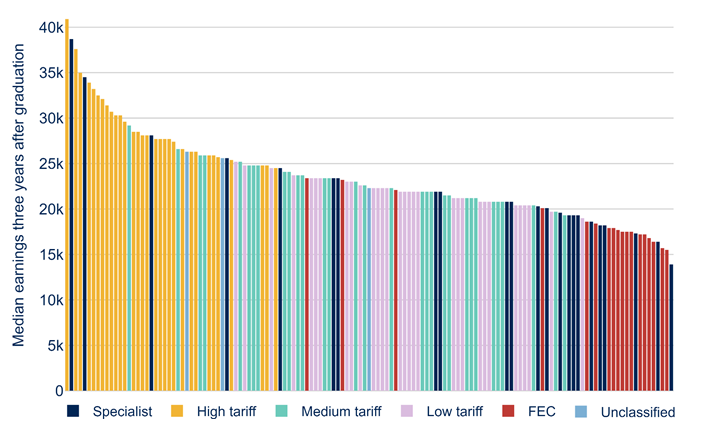

Take, for example, this cut of the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO) data measure, which is based on graduates in employment or further study three years after graduation.

Distribution of median earnings three years after qualifying from a degree course, by type of provider

Source: DfE published LEO data 2017-18]. 'FEC' is further education college. Providers with at least 100 employed graduates only, grouped using HEFCE analysis of 2014-15 entrants.

Each bar on this chart is a higher education provider, split into broad groups by tariff entry points, then specialists and further education colleges. The higher the bar, the higher the earnings three years after graduation. Graduates from the high tariff universities (shown in yellow) for the most part gain the highest earnings.

All credit to these universities and their graduates for these outcomes, but it’s worth also considering patterns of recruitment. The universities shown in yellow also have the lowest proportions of students from neighbourhoods with the lowest rates of access to higher education, which are mostly in the parts of the country with the lowest levels of productivity and growth: post-industrial towns and parts of cities across the north and midlands, and coastal towns.

They also recruit more of their students nationally, so their graduates are more likely to be mobile and ready to move for work.

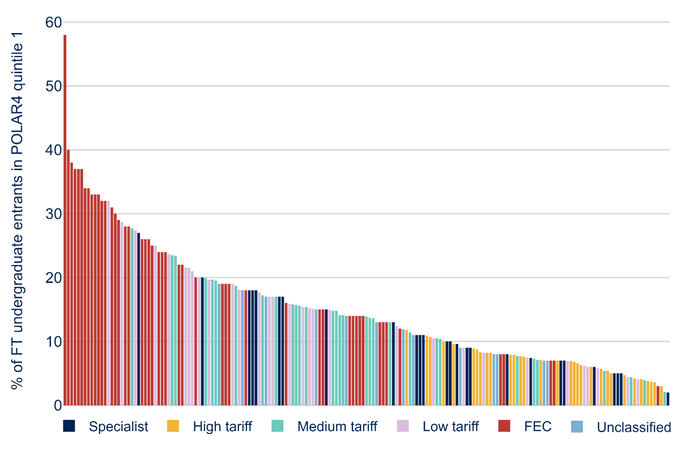

Distribution of students from low participation neighbourhoods, by type of provider

Source: OfS analysis of HESA and ILR data 2019-20. 'FEC' is further education college. See more information on this data

Further education colleges and lower tariff universities, shown in the red and pink bars above, recruit higher proportions of students from disadvantaged neighbourhoods and more students from their local area – and their graduates are more likely to stay there for work. This in itself affects their opportunities, particularly outside London and the greater south-east, as demonstrated below.

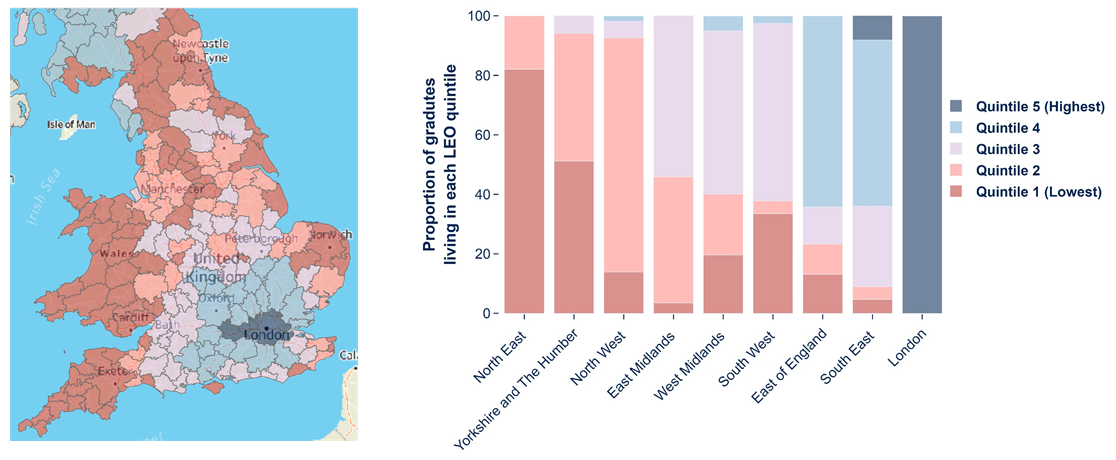

Regional variation in well-paid jobs: Distribution of LEO quintiles based on graduates earning over £23,000 or in higher study

Source: LEO quintiles based on earnings and study three years after graduation. Grouped into the regions using the closest fit. Map: Copyright Mapbox OpenStreetMap 2021

If you split the graduate population into earnings quintiles, the areas with most graduates in well-paid jobs are virtually all in London and the greater south-east. All graduates in London live in the highest quintile areas, all graduates in the north-east live in the bottom two quintiles, and this applies also to most of the graduates living elsewhere across the north of England.

So there is a strong link in England between where you come from, whether and where you go to university, and your career prospects beyond that. Can we do anything about this or is it beyond the influence of higher education? Here are two things we can do.

Firstly, we can shift the patterns of entry to courses in the highest tariff universities, which command the highest graduate earnings. Through the access and participation plans they have agreed with the OfS, these universities have committed to recruiting an additional 6,500 young people from the most underrepresented neighbourhoods each year. This is being achieved by creating pathways that cut through the academic, financial and cultural barriers to the most selective courses.

A week after 2021 results day, there were 2,500 more applicants with places in English higher education from the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods compared with last year, but 8,500 more from the most advantaged. So we are improving opportunity, but we are a long way from equality of opportunity, which is the goal for access and participation plans.

This is more important than ever, given what we know about the disruption the pandemic has caused for schools and families in the most disadvantaged communities across the country. With improved finance coming for lifelong learning, I hope we can also extend these opportunities to people who do not want to enter university directly from school and create stronger routes through further education and work.

Secondly, we can work with businesses and public services to improve the opportunities for people who want to study and work in the place where they grew up. The OfS is testing new ways of working between universities, colleges and local employers to support this.

This includes projects such as Rise in Manchester, Gateways to Growth in Norfolk and Graduate Workforce Bradford which are creating new approaches to supporting local students through their transition between graduation and work. Also Student Knowledge Exchange Re-imagined in Staffordshire and Birmingham, the Innovation Creative Exchange in Huddersfield and the Knowledge Exchange Toolbox in Plymouth which are enabling students to solve problems with local businesses and community groups during their studies, so they have better connections with and readiness for the workplace.

Through the short course trial announced last month, we will support more flexible routes for people to study whilst they are in work, improving their own career prospects and the productivity of their employers.

Returning to the OfS’s first regulatory objective, our first duty to students must be to support them to succeed whilst they are at university or college. But we are seeing a step change on access to the most selective courses and new ways of working between universities, colleges and local employers. This means that the next generation of students should have a better chance to gain the full benefits of higher education, wherever they come from.

This is an edited version of a keynote address given by Chris Millward at the Institute of Student Employment student recruitment conference on 30 June 2021.

Comments

Report this comment

Are you sure you wish to report this comment?