A matter of principles: Regulating in the student interest

In autumn and winter 2020-21 the Office for Students (OfS) will be launching a series of consultations as we review and reset our regulatory requirements. This Insight brief sets the context for this work. It explores the idea of principles-based regulation, which is the predominant approach the OfS takes in its regulatory framework. It also looks at the risk-based approach we take to making regulatory decisions and how we are continuing to reduce the administrative burden for the universities and colleges we regulate.

- Date:

- 6 October 2020

Read the brief

Download the Insight brief as a PDF

Read the Insight brief online

Introduction

How should regulators regulate? The answer depends on why regulation is needed, what is being regulated, who or what it is designed to protect, and what the regulator wants to achieve.

The Office for Students (OfS) regulates higher education in England, in the interests of students. Our aim is to ensure that English higher education is delivering positive outcomes for all students – past, current and future. In particular, we want to ensure that students from underrepresented and disadvantaged groups have the opportunity to participate in and succeed at and beyond university or college.1

The OfS is predominantly a principles-based regulator. We regulate through a set of conditions which focus on the outcomes we want to see for students. These conditions, described in our regulatory framework, set out the minimum levels, or ‘baselines’, that a higher education provider must achieve and demonstrate to be registered with the OfS.2 We adopt a risk-based approach to monitoring compliance, targeting our work where it is most needed – on those providers most at risk of breaching our conditions – and focusing on reducing burden on those that do not pose a specific regulatory risk.

As autonomous institutions, providers have the freedom to innovate and pursue excellence above these minimum baselines as they see fit, and we seek to create an environment that facilitates that. Our approach reflects the diverse nature of the sector we regulate and helps to maintain and strengthen its international reputation for innovation and excellence.

Reviewing and resetting our regulatory requirements

We are confident that our approach is the right approach for students and the sector. But we want to articulate more clearly why we think this: to step back from the detail and consider the bigger picture, drawing on our experience of registration and regulation since our establishment in 2018.

Higher education, like other sectors, is weathering a tremendous storm as it continues to navigate the uncertainties and challenges of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. In spring and summer 2020 we paused some of our regulatory requirements, adapting our approach to reduce any unnecessary burden and to support providers as they worked to support and protect their students during lockdown. We want to learn from this more recent experience.

We now plan a phased resumption of our requirements, but we do not intend to reinstate them exactly as before. This is an opportunity for us to rearticulate how and why we regulate, and how the different aspects of our regulation and regulatory objectives fit together. Returning to the purpose of our regulation in this way has prompted renewed focus on those objectives concerning the quality of higher education and equality of opportunity in higher education, which are at the heart of our work.

This Insight brief sets the scene for this work. It looks at the benefits and challenges of principles-based regulation and the rationale for our risk-based approach. We hope that it will inform and stimulate discussion, and encourage its readers to engage with the issues and questions we will be raising in the coming weeks and months.

Principles-based regulation

There is an extensive body of academic work on the development and application of principles-based regulation, and of the risk-based and outcomes-focused approaches that complement it. Much of this charts a broad shift over recent decades, across a number of sectors, from ‘rules-based’ to ‘principles-based’ approaches to regulation. However, it also emphasises that the appropriateness and potential effectiveness of a particular approach will depend on a number of factors, including the degree of complexity and innovation in a sector, the nature of the risks being regulated, and the characteristics of the community being regulated.3

The principles-based approach, now well established in the UK, was implemented in financial services regulation in the 1990s. Professor Julia Black and her co-authors, whose analysis we draw on throughout this Insight brief, define it as a set of ‘high-level, broadly stated rules or principles’ with ‘broad application to a diverse range of circumstances’.4

A principles-based approach explains the reasons behind the principle. It tends to be concerned with qualitative standards of behaviour: the skill, diligence and reasonableness with which organisations conduct their business and the fairness with which they treat their customers.5 It lends itself well to a focus on outcomes, setting out the overarching goals (for example ‘a high-quality academic experience for students’) that the regulation is there to achieve.

By contrast, a ‘rules-based’ approach broadly relies on enforcing compliance through clearly defined, specific prescriptions. It may be more concerned with processes and outputs, and generally allows more limited scope for judgement or discretion on the part of the regulator. It can provide greater certainty and reduce compliance costs, and can be a sensible and proportionate approach: a motorway speed limit restriction, for example, may be seen as a cost-effective approach that lets motorists know exactly what is and isn’t permitted.

Both approaches have their challenges and limitations. Principles-based regulation can generate uncertainty and a perceived lack of predictability. We discuss this and other issues below. Criticisms of the rules-based approach point to its propensity to foster ‘creative compliance’ – obeying the letter of a rule while undermining its spirit – and a ‘box-ticking’ mentality. It can also risk losing sight of the overall objective – in the speed limit example, road safety, including whether a driver may be driving unsafely despite complying with the rule.6

Finally, although the two approaches are conceptually distinct, it is important to note that in practice many systems combine elements of each. We discuss this in the context of the OfS’s regulation in the next section.

Applying a principles-based approach to higher education regulation

Our rationale for the adoption of a predominantly principles-based approach in higher education regulation is set out in part I of the OfS’s regulatory framework:

‘The regulatory approach is designed to be principles-based because the higher education sector is complex, and the imposition of a narrow rules-based approach would risk leading to a compliance culture that stifles diversity and innovation and prevents the sector from flourishing. This regulatory framework does not therefore set out numerical performance targets or lists of detailed requirements for providers to meet. Instead it sets out the approach that the OfS will take as it makes judgements about individual providers on the basis of data and contextual evidence.’7

We regulate a wide range of providers, from large, multi-faculty universities to small private companies offering vocational courses tailored to specific industries. Their student populations can also vary widely. The conditions in our regulatory framework apply broadly, to a diverse range of universities and colleges in a diverse range of circumstances. They are framed in a way that makes clear the reasons for the principles set out in them. So, for example, Condition E2 states that a provider’s management and governance arrangements ‘must be adequate and effective to deliver […] public interest governance principles and provide and fully deliver the higher education courses advertised’.8

A number also refer to standards of behaviour, but without stipulating that providers must do things in a particular way. They focus on the outcomes we want to see rather than specifying the ways in which those outcomes should be achieved. This gives universities and colleges the flexibility to meet them in ways they judge best for their context and their students.

Academic quality and equality of opportunity

Higher education is potentially life-transforming: it can pave the way for a rewarding career and a fulfilling life. The OfS wants all students with the desire and ability to go to university or college to have the opportunity to receive a high-quality higher education with successful outcomes regardless of their background.

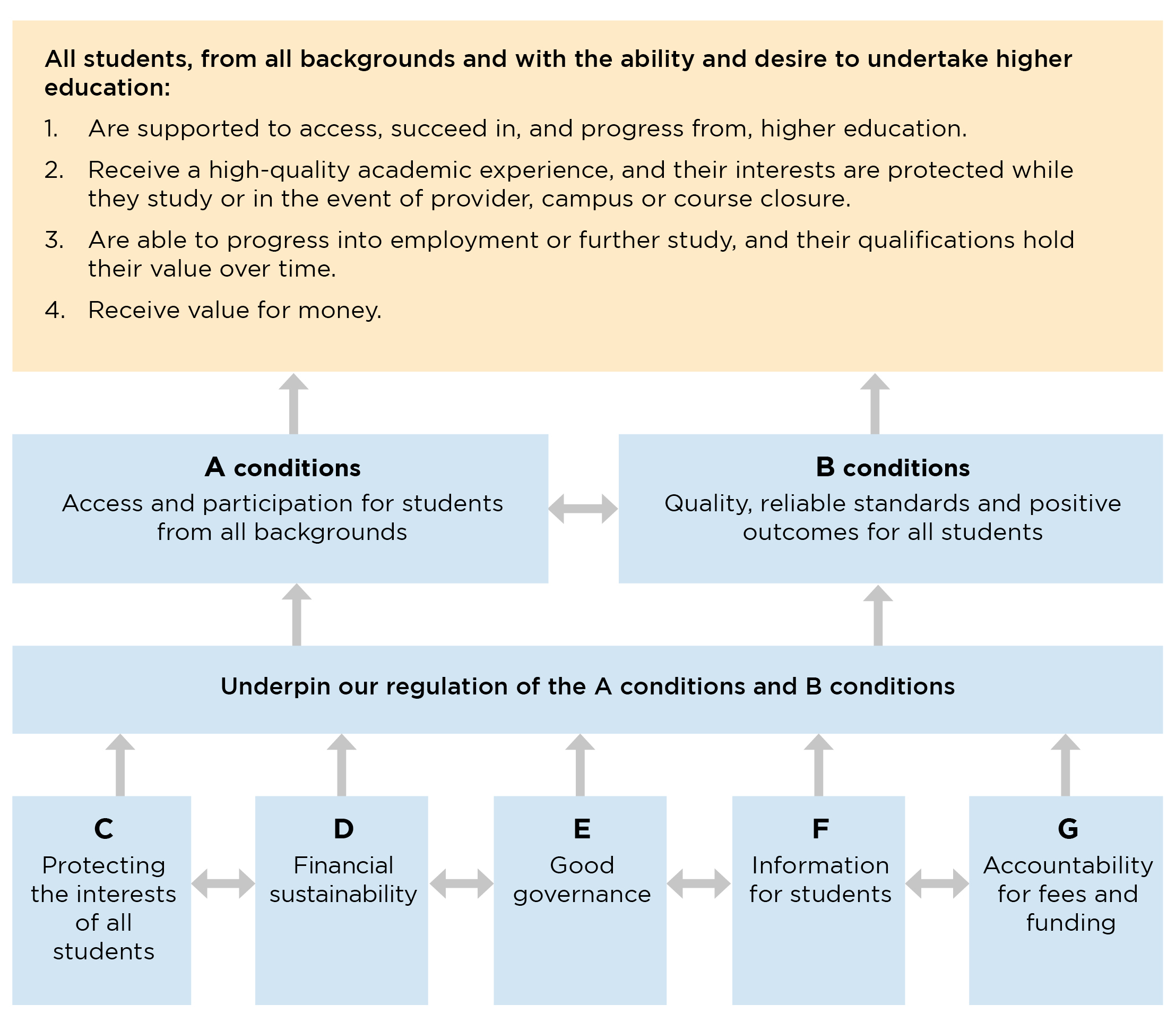

Our approach is designed to ensure that these two areas of regulation – quality and equality of opportunity – reinforce one another for the benefit of students. The ‘A conditions’ in the regulatory framework are about access and participation: how higher education providers will improve equality of opportunity for disadvantaged and underrepresented groups to access, succeed in and progress from higher education. The ‘B conditions’ are about the quality and standards of higher education provision: for example, that providers must deliver well-designed courses that meet sector-recognised academic standards (Conditions B1 and B5).9

The other requirements we impose (see Figure 110) underpin our regulation of these areas. For example, a university or college that is poorly managed or governed (the ‘E’ conditions) may not be adequately supporting students to have a high-quality educational experience. If a provider has financial difficulties (the ‘D’ conditions), this may affect the quality of the student experience and the value for money that students (and the taxpayer) receive.

Figure 1: OfS conditions of registration

Balancing principles- and rules- based approaches

A complex and innovative higher education sector is best regulated through a principles-based approach. However, we do, in some circumstances, adopt a more rules-based approach, or an approach which combines both rules-based and principles-based elements, where we are confident that this will allow us to deliver our regulatory objectives across a diverse sector in those particular circumstances.

For example, where we impose a specific condition for an individual provider because we have identified increased risk, we are more likely to use a rules-based formulation. This is because we have a particular concern and want clearly to specify whatever action is needed from the provider.

Similarly, in our condition Z3, introduced in July 2020, we took what could be characterised as a ‘hybrid’ approach. The condition, designed to protect sector stability and integrity (a principle), prohibits the use by higher education providers of ‘conditional’ unconditional offers (a rule).11 As we noted at the time, however, it was a response to the unprecedented circumstances of the coronavirus pandemic, and the need to give providers as much certainty as possible. The approach we took is not an indication of the approach that we would be likely to take in more normal circumstances, in large part because such a tightly specified rule makes it more difficult for providers and the OfS to respond to evolving business practices in a changing environment.

Risk-based regulation

Throughout the regulatory framework, we refer to ‘risk’ and to ‘risk-based’ regulation. These terms are often used in conjunction with principles-based regulation. The two approaches are mutually reinforcing, although they describe different things.12

The OfS regulates universities and colleges on the basis of the regulatory risks they pose, not on the basis of their size, what type of organisation they are or the length of time they have been providing higher education (although we will consider those factors where they are relevant to an assessment of risk). In this context, ‘regulatory risk’ means the risk of the university or college breaching one or more of its conditions of registration. We will assess both the likelihood of something happening and the severity of the impact (on students in particular) if it does happen.

Risks may arise from issues within the provider itself, or from the environment in which it is operating. An obvious example of the latter is the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on higher education in England.

Our primary focus is on the conditions relating to access and participation (the A conditions) and quality and standards (the B conditions). In practice, this means we want to identify universities and colleges performing below, or close to, the minimum baselines set out in our conditions of registration: in other words, those that pose the greatest risk to students. We then decide whether and how to intervene, depending upon the risks posed. For example, high-quality providers that deliver successful outcomes for students from all backgrounds should experience reduced regulatory burden as a result of our regulation of quality.

Developing our approach

No system is without its flaws, and a number of commentators have examined the challenges as well as the benefits of a principles-based approach. We look briefly at three broad themes requiring our particular attention as we review and rearticulate our regulatory requirements.

Clarity and transparency

As discussed, principles are flexible and adaptable, and can apply across a diverse range of contexts and circumstances. However, they may also be less precise, and less easy to set out in a definitive way, than detailed, prescriptive rules. Those being regulated may be unsure about what they need to do to ensure compliance. They may adopt an overly cautious approach, seeking guidance or reassurance from the regulator about what they ‘have to do’ instead of having the confidence to apply judgement and innovation in their own context. The regulator, in turn, may respond with a proliferation of guidance that tries to clarify and assist, but risks creating further confusion and uncertainty. These challenges may be particularly present in a newly established regulatory regime.

We know that we need to get this balance – between too much and too little guidance – right as we rearticulate, develop and consult on our approach over the coming months. We also recognise the importance of consulting students, universities and colleges, representative bodies and other stakeholders in the development of our regulatory approach. We are taking a phased approach to consultation, to minimise the burden that consultations create for stakeholders.

Communications and engagement

This theme has close links with the first one. Good principles-based regulation requires respectful, constructive relationships between the regulator and the regulated. We want to foster honest and open dialogue with providers based on a shared understanding of our expectations. In a letter to providers in July 2020 we undertook to embed the model of engagement we operated during the pandemic, to help providers to navigate our regulatory requirements.13

Reducing burden

A principles-based approach can increase burden, since the regulated must use their own judgement to determine how best to comply with the principles. Smaller regulated entities may lack the resources and expertise to do this.

In our July 2020 letter we restated our intention to target attention where it is needed and reduce burden for providers that do not pose increased risk. Linked to this, we announced our expectation that there would be less need for enhanced monitoring now we are in a more established regulatory environment. We will also be taking forward other actions to reduce bureaucratic burden, including those set out in the September 2020 strategic guidance letter from the Universities Minister.14

Conclusion

A practical, evidence-based application of the principles-based approach to regulation provides us all with the opportunity to respond actively and creatively to support and protect the interests of students at this time. We look forward to working with students, providers and everyone else with an interest in higher education as we review and reset our regulatory requirements over the coming months.

1 In this Insight brief we use the terms ‘university and college’, ‘provider’ and ‘higher education provider’ to refer to the range of institutions we regulate.

2 Available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/regulation/the-regulatory-framework-for-higher-education-in-england/. The framework sets out a number of conditions providers wishing to register with the OfS will need to satisfy. Registration means a provider can apply for government funding for research and teaching, and that their students can apply for government tuition fee and maintenance loans and visas to study in the UK if they need them (OfS regulatory framework, pp28-30).

3 Decker, C, ‘Goals-based and rules-based approaches to regulation’, Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy research paper 8, 2018, p5 (available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulation-goals-based-and-rules-based-approaches).

4 Black, J, Hopper M and Band, C, 2007, ‘Making a success of principles-based regulation’, Law and Financial Markets Review, p192, available at LSE Research Online (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/23106/).

5 Black et al, ‘Making a success of principles-based regulation’, p192 and passim.

6 For a discussion of this point see Decker, ‘Goals-based and rules-based approaches to regulation’, p16.

7 OfS regulatory framework, p15.

8 OfS regulatory framework, p112.

9 OfS regulatory framework, pp83-95.

10 Figure 1 provides a simple visual representation of the relationships between the areas we regulate through different groups of conditions. It does not represent a hierarchy in which compliance with some conditions is more important than compliance with others. All providers are required to comply with all applicable conditions of registration as set out in the regulatory framework.

11 See ‘Regulatory notice 5: Condition Z3 – Temporary provisions for sector stability and integrity’ (OfS 2020.33, available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/regulatory-notice-5-condition-z3-temporary-provisions-for-sector-stability-and-integrity/).

12 For a discussion of risk-based regulation, see Black, J, and Baldwin, R, ‘Really responsive risk-based regulation’, Law and Policy 32(2), spring 2010, available at LSE Research Online (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27632/).

13 See ‘Update on the Office for Students’ approach to regulation and information about deadlines for data returns’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/update-on-the-office-for-students-approach-to-regulation-and-information-about-deadlines-for-data-returns/).

14 Available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/regulation/guidance-from-government/.

Describe your experience of using this website