Student accommodation

Working with universities, colleges and other stakeholders, the Office for Students (OfS) is producing a series of briefing notes on the steps universities and colleges are taking to support their students during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The notes do not represent regulatory advice or guidance – their focus is on sharing ideas and responses, and signposting to further information. They reflect current information as at date of publication in a rapidly evolving situation.

This briefing note looks at the ways in which universities, colleges and others are supporting the accommodation needs of their students during the outbreak, and signposts to sources of advice and information.

- Date:

- 22 April 2020

Read the briefing note

Download the briefing note as a PDF

Read the briefing note online

Student accommodation has emerged as a pressing concern for large numbers of students during the coronavirus pandemic. Their concerns are many and varied. Students still living in their term-time accommodation may be worrying about whether their tenancy will be extended if they need it to be. They may be anxious about falling into rent arrears. They may be fearful about whether they will be able to get help if they become ill. Those who have returned to their family home may be unsure how and when they will be able to retrieve their belongings, whether their belongings are safe in an unoccupied house or hall of residence, or if they will have to pay rent for accommodation they are now not using.

The problems range from the immediate – such as how students who are self-isolating can share communal kitchens and bathrooms safely – to the longer term – such as whether students will be held to tenancies due to commence in summer 2020 in the event of continuing uncertainty about the impact of the virus on learning, teaching and research activity.

This briefing note looks at the ways in which universities, colleges and others are supporting the accommodation needs of their students during the outbreak, and signposts to sources of advice and information. We are acutely aware of the importance to students of accommodation issues, the confusion and uncertainty that many of them are currently experiencing, and their concern that disruption and financial loss be minimised wherever possible.

We are also aware of the implications for universities and colleges of loss of income from campus-based accommodation as a result of the pandemic. Universities UK has estimated that the UK sector is facing losses of around £790 million from accommodation, catering and conference income in the final 2019-20 term, and for the 2020 Easter and summer vacations.1

The note does not constitute regulatory guidance – the OfS has no remit to regulate providers of private accommodation directly. Nor do we have a role in resolving individual disputes between students and their universities or colleges. The aim is, rather, to disseminate ideas, approaches and practice. In so doing, we are not stipulating particular approaches or in any way endorsing the actions of specific institutions. Even where we are highlighting an action that may be beneficial to students, this should not be taken as a wider endorsement of that institution or of their approach to accommodation during the coronavirus pandemic.

The note’s main focus is on students who normally live away from home, although we also want to acknowledge the large proportion of students who commute to their university or college from their own home, or the home they grew up in, and who will be facing their own challenges in continuing their studies at this time.2

Student accommodation: an overview

Student accommodation comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. In 2018-19, of the full-time and sandwich students studying in the UK, only 19.4 per cent of undergraduates and 15.5 per cent of postgraduates lived in provider-maintained property, or in student halls owned by a university or college.3 Most students who live away from home are in accommodation that is not directly owned by universities and colleges. Many students rent purpose-built student accommodation from one of a number of major UK student housing management and development companies. Others live in houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) rented from smaller private landlords. This diversity of accommodation type and ownership means that there is a similar lack of uniformity in rental arrangements and the support that students can expect.4

In the period before ‘lockdown’, which started on 23 March 2020, the government advised students to return to their out-of-term homes if possible (although only if they were able to do so without using public transport).5 The latest government advice is that any students who have not gone home should now stay where they are and not attempt to travel while the current restrictions are in force. This advice applies whether they are living in student halls or private rented accommodation.6

We do not, at present, know exactly how many students are still living in term-time accommodation. But the indications are that large numbers of students, both domestic and international, did not (or could not) return to their home address before the lockdown. A Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) poll of 1,000 undergraduate students found that around 45 per cent of respondents were still living at their term-time address at the end of March 2020.7

The government has published guidance on isolation in university and college halls of residence and HMOs. The guidance states that universities and building managers of private halls will need to ensure that self-isolating students can receive the food and medicines they need for the duration of their isolation. It also advises students in HMOs to discuss their circumstances with their landlord and their institution, who should then work together to ensure necessary support is in place.8

The government has stressed that there should be no evictions from university-owned halls during this period. It has also encouraged universities and colleges to make clear to the managers of any privately owned halls of residence in their area that evictions would be unacceptable. If a housing provider is unable to accommodate a student, work must be done with the local authority, letting agencies and other local partners to prevent students being made homeless.9 In the private rental sector, new government guidance in response to the coronavirus pandemic has extended the notice period for evictions to three months for certain types of tenancy.10

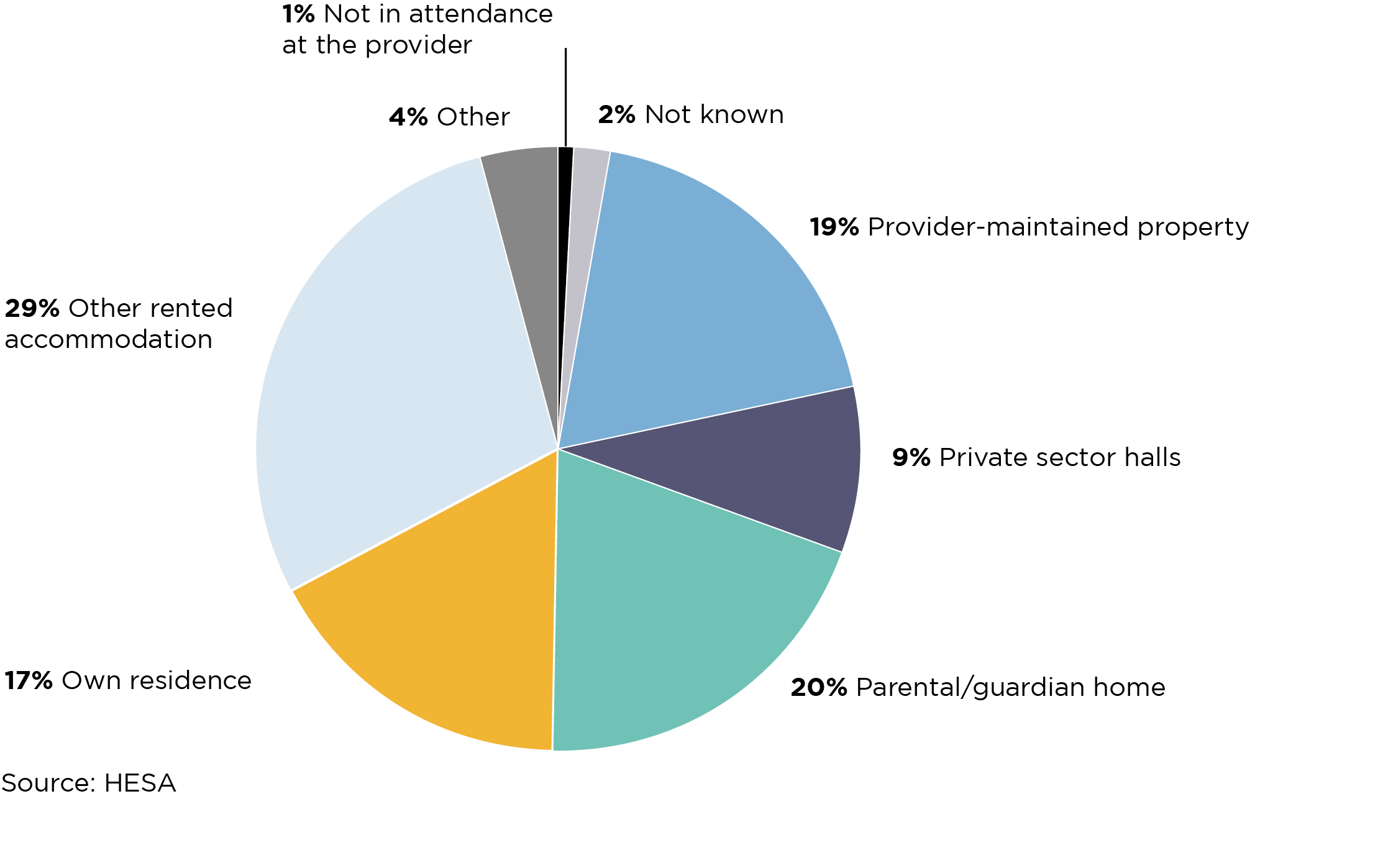

Figure 1: Full-time and sandwich students studying in the UK by term-time accommodation, 2018-19

Figure 1 is a pie chart showing the type of term-time accommodation lived by full-time and sandwich students who are studying in the UK, 2018-19.

It shows that there is a wide variation in the type of accommodation these students live in. Specifically:

- 19 per cent lived in a provider-maintained property

- 9 per cent lived in private sector halls

- 20 per cent lived in their parental or guardian home

- 17 per cent lived in their own residence

- 29 per cent lived in other rented accommodation

- 4 per cent selected ‘other’

- 1 per cent were not in attendance at the provider

- For 2 per cent of students, it is not known what their accommodation was.

Vulnerable students

Many students remaining in student accommodation may face particular issues and difficulties in the circumstances. These include:

- International students: many intended or may still want to return to their home countries but have been prevented by borders being closed or difficulties in finding a flight.

- Care experienced students (students who have been in the care of a local authority, such as a children’s home or foster care): local authorities have a legal responsibility to support care leavers with the costs of out-of-term accommodation, although a number have extended this support to in-term accommodation costs during the pandemic.

- Students who are estranged from their families: this group does not have the same legal status as care leavers, but these students may have similar needs.

- Mature students, especially those in university or private sector family accommodation, may have additional caring and childcare responsibilities.

The government guidance stresses the particular importance of ensuring that international students, care leavers and estranged students are not required to leave their halls of residence, regardless of whether their contract is up or does not cover holiday periods, or if they are unable to pay their rent. In a similar vein, it emphasises the need for higher education providers to make sure that self-isolating disabled students, along with non-disabled students, are receiving the food and medicines they need.

Universities and colleges are thinking carefully about the needs of these and other groups of vulnerable students. Many have contacted their vulnerable students to reassure them that they will not be evicted, and that their needs will be met.

Student wellbeing

For all students left on a near-deserted campus, concerns about mental and physical health are especially pressing. Student halls often do not have gardens, balconies or other contained outdoor spaces. This limits students’ opportunities for outdoor exercise and relaxation, with knock-on implications for access to sunlight, physical health, and mental wellbeing.

Maintaining social connection remotely is paramount to ensure good mental health. Many higher education providers and private halls are using social media and other online technologies to keep in touch and help students socialise safely, and a number have already moved their mental health support online. The Department for Education and the OfS are working with the sector to consider how universities and colleges might offer additional support.

University of Hull: support services

The university’s student services team is providing support to all students – whether on or off campus – through telephone calls, live chat and video conferencing. This includes support relating to mental health, academic issues, financial issues, and immigration and visa compliance. Tutorial support is offered to students with specific learning differences such as dyslexia and dyspraxia. All the university’s vulnerable students have been proactively contacted to ascertain any issues and provide support as required.

The university has launched a new ‘Exceptional Circumstances Fund’ to support students who have lost an income stream on which they rely and that cannot be obtained from any other source – for example, as a result of lost or reduced income from employment.

Separate rooms are available for students needing to self-isolate along with a package of support which includes daily check-ins from the student welfare team, who also ensure that they have food and other essential items.

Physical distancing in student accommodation

Student accommodation presents challenges for physical distancing if students need to self-isolate. Shared spaces such as kitchens, bathrooms and living rooms are common across a range of accommodation types, and can increase the risk of cross-infection. Government guidance emphasises the need for universities and colleges to consult with local Public Health England protection teams in making decisions about self-isolation where a student has symptoms of coronavirus, and to ensure that self-isolating students have the food and medicines they need for the duration of their isolation.

Some universities are housing students in self-contained units in order to stop the spread of the virus in communal areas. It is particularly important to protect those students who are at greater risk of becoming seriously unwell with coronavirus (such as those with underlying health conditions). Moving these students to ensuite accommodation or self-contained flats - so that they do not have to share a kitchen or other facilities - will help to keep them safe.

Providers are also dealing with the task of ensuring students’ security, especially in large purpose-built accommodation, at a time when they may be experiencing staff shortages.

Landlords’ repair obligations have not changed. It is in the best interests of both tenants and landlords to ensure that properties are kept in good repair and free from hazards, and that urgent health and safety issues are swiftly addressed.11

University of Greenwich: Maintaining student wellbeing

The students’ union and the university are organising a range of virtual events, games and other interventions for students remaining in halls. These include virtual language-learning, volunteering opportunities, fitness sessions, study groups, mindfulness activities, quiz sessions, book and poetry discussions, and ‘Netflix parties’. There is an active Facebook student community group. The students’ union and the university’s accommodation services have arranged pastoral phone calls to check in with residents, assist with any queries, provide assurance and offer help if needed. Additional student wellbeing support, including via Big White Wall, a mental health support community, is available online and by phone.

Rent and arrears

Many students who have returned to their family home are worried about paying rent for accommodation they are no longer using. By mid-April over 60,000 people had signed a petition calling on student accommodation providers to waive rent for the third term for those who have returned home.12 Some students are organising rent strikes and have gained concessions.13

Many universities and colleges are cancelling rent for the third term for students who have vacated their rooms. Some have waived rent for all students, regardless of whether they are still in their accommodation.14

As of 11 April 2020, according to Unipol, the student housing charity, 60 universities in England had ‘confirmed that they would refund, waive, or terminate contracts’. A further 52 had stated that ‘they would continue with current contracts…or were yet to make a decision’.15

A number of student accommodation management companies have waived fees for the third term of the current academic year if a student has vacated their accommodation.16 Some private student rental agencies and landlords have reduced rents substantially. We understand that other student accommodation companies are expecting students to continue to fulfil their contracts, and to pay full rent.17

The government has reassured students that they will be paid their maintenance loan as usual for the third term.18 However, the National Union of Students (NUS) has expressed concerns that this will still not be enough to allow some students to cover their rent.19 A 2018 NUS and Unipol accommodation cost survey showed that, on average, rents accounted for 73 per cent of the maximum student finance maintenance loan.20 Many undergraduate students studying in England are not eligible for the maximum loan and rely on their parents and/or part-time work to help meet their living costs.

With thousands of shops and businesses closed until further notice, and the prospect of an uncertain job market for some time to come, many students have lost the part-time work they often undertake over the holidays and during term time, and will not be eligible for universal credit or housing benefit. Their parents may also have experienced a loss in income.

In these circumstances, and as the quotes below suggest, rent arrears may be, or become, a pressing problem for many students. The NUS has asked, among other things, that ‘all [student] renters who are financially impacted by the coronavirus must have their rents subsidised, significantly reduced or waived entirely for six months’.21 We understand that some universities and colleges have written to private student landlords encouraging them to be flexible in the current unprecedented circumstances.

There has also been recognition, in the press and elsewhere, that landlords may themselves be facing financial pressures. The government has published details of a package of measures ‘to ensure support is available where it is needed for landlords’.22

Beyond the summer term, many students will have already signed tenancy agreements for the next academic year. With uncertainty about when government restrictions will be lifted and providers can begin face-to-face teaching, many will be worried about whether they will be paying for accommodation they may not live in. Universities and colleges will also potentially suffer further loss of income from their student halls if this does happen, as may other accommodation providers. This could have wider implications for local economies and communities that universities, working with the local authority and other partners, will be attempting to identify and mitigate.

Student accommodation management companies: Supporting students during the pandemic

Certain student accommodation management companies have allowed students who have moved out to cancel their rent for the third term. They have also produced regular updates, FAQs and other communications, discussed payment plans with individual students, and collated information about university-specific hardship and financial support schemes for residents in difficulty.

Some companies are assisting with shopping and other services, and helping to support students’ mental and physical health and wellbeing – for example, providing details of university-specific and national online mental wellbeing and health services, setting up residents’ online chat groups, and providing access to online fitness classes.

Student perspectives

These quotations are from students and students’ unions responding to an invitation from the NUS to contact us about their experiences of accommodation during the coronavirus crisis. They have been anonymised to protect identities.

‘The universities in this city have been very good with cancelling contracts and waiving final term rent payments.’

‘I asked for my contract to be terminated early….The answer was ‘no’ and the company said it would get my guarantor involved.’ [Student in accommodation managed and owned by a private company]

‘Overall I feel let down and ignored by my letting agency. I emailed them regarding concerns around the lack of information regarding rent reduction and payment options...[and] was met with a generic email…which did not answer my questions and frankly felt distant and uninterested….I understand that it is a complicated and chaotic time but it is confusing when some measures are being taken with certain companies and not others.’

‘The students’ union and the university have written a joint letter to private landlords, with input from the local landlords’ association.’

‘Some private halls have offered cancellation policies… [with] very short deadlines and specific terms that make it difficult for students to cancel their tenancies, such as the need to travel to collect belongings even though it directly contradicts government advice. One is demanding pages of personal, medical and financial information…before they consider cancelling contracts.’

Staffordshire University and Students’ Union: working together to support private sector student tenants

Staffordshire University and Staffordshire University’s Students’ Union are working together to help students in private accommodation, as well as those in university accommodation, to access food, cleaning and sanitary products, and health and wellbeing support. During the first week of the lockdown, the Students’ Union contacted student tenants through Greenpad, its accommodation service, to find out whether they intended to remain in their accommodation, identify any immediate support required, and signpost relevant advice and support services.

The Students’ Union is working closely with contractors to manage essential repairs and maintenance and to ensure compliance; liaising with private landlords to deal with queries related to student finances, and working to agree payment plans as required; and providing students living in private sector accommodation with template letters to refer to when contacting their landlords with rent queries.

The university and the Students’ Union are also working together to organise events and activities for all students still living on or near the university, including video game tournaments, cookery demonstrations, fitness classes and a virtual ‘One Staffs Café’ designed to bring together Staffordshire University students from across the globe.

Conclusion

Higher education providers are facing considerable challenges in providing safe accommodation for their students. Many if not most are taking a fair and balanced approach to decisions concerning accommodation charges. They are also working in partnership with their student unions and other partners to support their students’ wider welfare and wellbeing.

The complexities and uncertainties surrounding the pandemic make clear, transparent communications with students even more important. In relation to accommodation, this might include the following (this list is not exhaustive):

- Clear, up-to-date information about how accommodation is being maintained, cleaned and kept safe.

- Detailed information about how to self-isolate in a house with communal areas, and the support available to students.

- What students can expect to pay for the summer term, whether they are using the accommodation or not.

- Regular contact with vulnerable students, tailored to their particular needs.

- Regular dialogue with students’ unions to identify student accommodation issues and initiatives.

- How the university or college is working with private landlords and student accommodation companies to try to ensure students are fairly treated.

- How students will be helped if they are unable to pay their rent.

- How students can maintain their wellbeing, physical health and mental health during physical distancing.

- Ensuring that students are aware of the new protections against evictions.

Student accommodation: information and resources

The government has published guidance on isolation in educational residential settings, including student halls of residence and houses in multiple occupation (HMOs).

The government has published advice for households whose members may be infected with coronavirus.

The Department for Education has published frequently asked questions from university students on how the coronavirus might impact higher education. There is a section on accommodation.

Universities UK has published answers to common questions relating to COVID-19 and students who continue to live on campus, as well as those living in privately rented accommodation.

Citizens Advice has information on what to do if you can’t pay your rent. There is a range of tenancy types and rental arrangements, and the laws and regulations governing them may differ accordingly. In general, payment of rent is a contractual obligation – students should seek advice if they are considering withholding payment of rent or struggling to keep up with payments.

The National Code website has information and advice on coronavirus in student accommodation for housing suppliers.

Help for students with accommodation issues

Government changes to eviction

New government guidance has extended the notice period for evictions to three months for certain types of tenancy. Court proceedings for eviction are on hold until at least 25 June 2020, regardless of when the landlord in question applied to the court. In practice, these protections mean that students benefitting from those types of tenancy agreements cannot be evicted before the end of June.

If they are threatened with eviction during the pandemic, students should contact the housing officer at their provider and/or student union, if there is one. Shelter, the housing and homelessness charity, also has advice on their website.

Report concerns to the Competition and Markets Authority

If students believe their accommodation provider is behaving unfairly during the pandemic, they can report them to the Competition and Markets Authority.

Students may also consider speaking with their local Trading Standards office about any concerns they have as regards their accommodation provider’s behaviour.

Complaints under accommodation codes

If a student’s landlord has signed up to an accommodation code of good practice, such as that run by Universities UK and GuildHE, or Unipol and ANUK, and they are having problems with the property or landlord, they can make a complaint:

Complaints to the Office of the Independent Adjudicator (OIA)

The OIA has published a briefing note for providers on possible complaints arising from the coronavirus situation which includes accommodation issues. There are also FAQs for students.

We thank those universities and companies that provided case studies. We are also grateful to Universities UK and to the National Union of Students (NUS) for their assistance.

The case studies and interventions described in these notes have been developed at pace. They are offered in the spirit of sharing practice that others may find useful and applicable to their own contexts.

1 See https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/news/Pages/Package-of-measures-proposed-to-enable-universities-to-play-a-critical-role-in-rebuilding-the-nation-.aspx Note: this link is no longer available on the Universities UK website.

2 As Figure 1 shows, a significant proportion of students – over one-third in 2018-19 – continue to live with their parents or guardians, or in their own homes, for some or all of their university course.

3 See https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-study

4 For the sake of brevity, this note provides information specifically on students in tenancy arrangements. The law may apply differently to other types of arrangement.

5 Government guidance, 21 March 2020 (now superseded). This text was amended 6 August 2021 to clarify the government’s guidance on isolation for residential educational settings at the time.

6 See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-isolation-for-residential-educational-settings/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-isolation-for-residential-educational-settings. This advice was repeated in a letter of 27 March 2020 from the Minister of State for Universities to students: see https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/coronavirus/letters-from-the-minister-of-state-for-universities/

9 See ‘Stay home’ section of the government residential educational settings guidance.

13 See https://thebristolcable.org/2020/04/bristol-coronavirus-students-letting-agents-rent-strike/ and https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/15/hundreds-of-students-in-uk-sign-up-to-rent-strike

14 See https://www.burnleyexpress.net/health/coronavirus/uclan-waives-student-accommodation-fees-2525064

16 See https://www.unitestudents.com/the-common-room/health-and-wellbeing/coronavirus-student-faqs and https://www.iqstudentaccommodation.com/an-update-from-us-on-covid-19

17 See, for example, ‘Students forced to keep paying for abandoned term-time flats’, The Times, 11 April 2020 (paywall).

18 See https://www.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-for-current-students

19 See https://wonkhe.com/blogs/we-can-avert-a-crisis-for-student-renters-but-only-if-we-act-fast/

20 See https://www.unipol.org.uk/acs2018, p11.

21 See https://www.nus.org.uk/en/news/press-releases/nus-demands-for-student-renters--open-letters-to-providers-of-student-rented-accommodation/ [no longer available]

Briefing note published on student accommodation during pandemic

Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Describe your experience of using this website