Findings from OfS quality assessments

Our recent quality assessments identified some common factors that can affect the quality of the higher education students receive. This brief examines the main risks to quality emerging from our published reports, under four headings: risks to delivery of courses and resources, risks to academic support and student engagement, risks to assessment of learning, and risks to academic leadership and oversight.

This brief does not constitute legal or regulatory advice, nor does it explain our regulatory decisions.

- Date:

- 22 October 2024

Read the brief

Download the Insight brief as a PDF

Read the Insight brief online

Introduction and background

Quality is at the heart of what students want and expect from higher education. The consistent delivery of high quality courses is a priority universities and colleges share with the Office for Students (OfS), the regulator for higher education in England.1

The recent Public Bodies Review report on the OfS identifies quality as one of the four areas where we should focus our efforts.2 We intend to bring together our work over recent years into an integrated approach to quality, drawing together quantitative and qualitative approaches and refocusing on regulating to secure continuous improvement across the sector.

Extending equality of opportunity and high quality courses go hand in hand. Improving equality without ensuring quality and standards will not lead to positive student outcomes, while ensuring quality and standards without improving equality of opportunity means that some students who could benefit will not.

Any university or college we register must meet our conditions of registration, including a set of requirements for quality and standards called the ‘B conditions’.3 This means that all students entering higher education can expect their course to meet or exceed our requirements for high quality.

As well as assessing institutions that are seeking registration or degree awarding powers, we assess whether institutions that are already registered are continuing to comply with our regulatory requirements.4

This Insight brief relates to our recent assessments of the quality of courses at a small number of institutions, in business and management and in computing. It explains the approaches and types of evidence used in these assessments and summarises the main risks we have seen to quality, to support universities and colleges to reflect on their own approaches in these areas. The more detailed individual reports are published on our website.5

The brief is not an exhaustive list of the ways universities and colleges might comply with the OfS’s conditions of registration, nor does it look at everything the conditions require in terms of quality. While these assessments focus on the minimum requirements for quality set out in conditions B1, B2 and B4 (summarised in Figure 1), institutions will want to consider how they can continue to improve their courses beyond those requirements, bearing in mind that appropriate practice in one institution may not be appropriate in another.

Most higher education courses delivered by universities and colleges in England are of high quality, and we know that universities and colleges undertake significant and continuous work to ensure that students receive high quality education. For them and others, we hope that this brief will shine a light on some recent outcomes from the quality work we do at the OfS.

Figure 1: Summary of conditions B1, B2 and B4

Condition B1: Academic experience

The provider must ensure that the students registered on each higher education course receive a high quality academic experience. This includes ensuring that each course:

- is up to date

- provides educational challenge

- is coherent

- is effectively delivered

- requires students to develop relevant skills, as appropriate to the subject matter of the course.

Condition B2: Resources, support and student engagement

The provider must take all reasonable steps to ensure:

- students receive resources and support to ensure:

- a high quality academic experience for those students

- those students succeed in and beyond higher education - effective engagement with each cohort of students to ensure:

- a high quality academic experience for those students

- those students succeed in and beyond higher education.

Condition B4: Assessment and awards

The provider must ensure that:

- students are assessed effectively

- each assessment is valid and reliable

- academic regulations are designed to ensure that relevant awards are credible

- academic regulations are designed to ensure the effective assessment of technical proficiency in the English language, in a way that appropriately reflects the level and content of the course

- relevant awards granted to students are credible at the point of being granted and when compared with those granted previously.

Note: For the full wording and requirements of these conditions, see OfS, ‘Securing student success: Regulatory framework for higher education in England’ (OfS 2022.69), November 2022.6

Background to the recent quality assessments

In 2022, we commissioned teams of assessors that included academic experts drawn from the higher education sector in England. We asked them to assess the quality of business and management or computing courses at a number of institutions, in relation to conditions B1 (academic experience), B2 (resources, support and student engagement) and B4 (assessment and awards).

Our assessors

Our assessors are current or recent members of academic staff from a range of institutions, with a range of relevant subject-specific and wider expertise. Applicants for the role are invited to an online assessment process and, if they are being considered as a lead assessor, to an interview. Assessors are trained by the OfS before undertaking their assessments. For the recent quality assessments, each team comprised a lead assessor, two other assessors, and a member of OfS staff to act as assessment coordinator.

Choosing where to look

We chose these subject areas because they are studied by large numbers of students. Business and management and computing are respectively the first and third largest subject areas in terms of the number of students registering each academic year.7 In addition, our data and intelligence suggested a risk that some courses in these subject areas were not complying with our quality conditions.

This kind of quality assessment lets us focus on the pockets of provision where students may not be doing as well, or where there may be an issue with quality.8 After choosing to look at business and management and computing courses in this cycle of assessments, we selected the institutions to assess based on the risk indicators we use in our general monitoring.

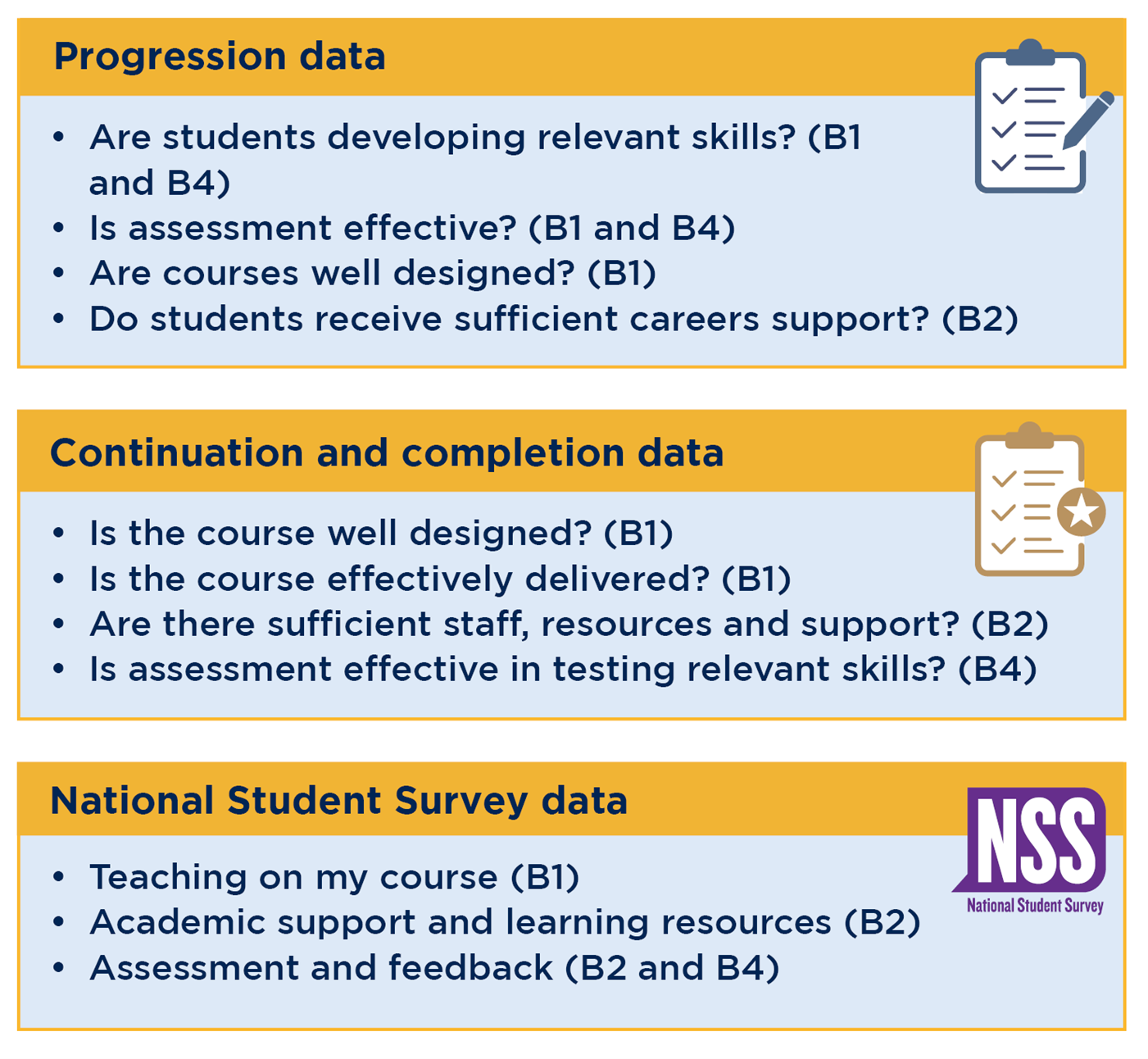

These included data on the outcomes for students at these institutions – how many continue in and complete their courses, and how many progress to appropriate employment or further study. In other areas of our work, we look specifically at performance in our student outcomes indicators. Here, we used the student outcome indicators to pose questions about the quality of courses. More detail is set out in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The use of data in scoping quality assessments, 2022-23

Progression data

- Are students developing relevant skills? (B1 and B4)

- Is assessment effective? (B1 and B4)

- Are courses well designed? (B1)

- Do students receive sufficient careers support? (B2)

Continuation and completion data

- Is the course well designed? (B1)

- Is the course effectively delivered? (B1)

- Are there sufficient staff, resources and support? (B2)

- Is assessment effective in testing relevant skills? (B4)

National Student Survey data

- Teaching on my course (B1)

- Academic support and learning resources (B2)

- Assessment and feedback (B2 and B4)

Note: B1, B2 and B4 refer to conditions of registration in our regulatory framework.9 Condition B3, relating directly to student outcomes, did not form part of these assessments.

We also looked at data about students’ experiences from the National Student Survey (NSS), which gathers students’ perspectives on the quality of their courses.10

We took a broad approach. When we looked at performance in the indicators across the sector, we considered those institutions falling into the bottom quartile of performance, though we did not use this as a hard threshold.

For this first cycle of assessments we focused on institutions with larger populations, both of students studying the subjects in question, and in terms of overall student numbers. This was because more students would be at risk from any issues with quality.

The choice of institutions was therefore based on a combination of the size of their student population, the number of indicators where performance indicated a potential concern, and their performance within those indicators compared with others.

We also checked whether third parties had notified us about any relevant issues.11 This was a final step to determine whether we should select one institution over another.

Student outcomes data

The performance of an institution in our student outcomes indicators – showing the proportions of students who continue in their studies, complete their studies, and progress to further study or appropriate employment – was not directly assessed as part of these quality assessments. Nor did we use the numerical thresholds for these outcomes set under condition B3 to select institutions, as these were still subject to consultation.

At present an institution’s performance in relation to student outcomes is assessed through our separate assessment of condition B3, though we intend to move towards a more integrated approach to assessments in future.12 The teams did, however, explore whether any underlying issues relating to conditions B1, B2 or B4 – for example, with the delivery of a course or the support available to students – were leading to problems with these outcomes.

Assessment method

We asked assessment teams to submit their findings to us in a report.13 All 11 of these reports have now been published on our website.

Because the assessment method was designed to identify particular risks, it did not test comprehensively whether an institution was complying with all of our quality requirements. Instead, each assessment team developed lines of enquiry specific to the university or college it was assessing. They explored these through site visits and meetings with a range of staff and students. The teams looked at the approaches in place to ensure high quality delivery, and how these worked in practice. They also looked at how an institution tested whether what it was doing was having the expected impact.

Student input was important throughout the assessment process, with the teams guided by information from NSS submissions and meetings with students and student representatives. The teams reviewed the published quantitative data available from the NSS, and comments submitted by students, which are not publicly available.14

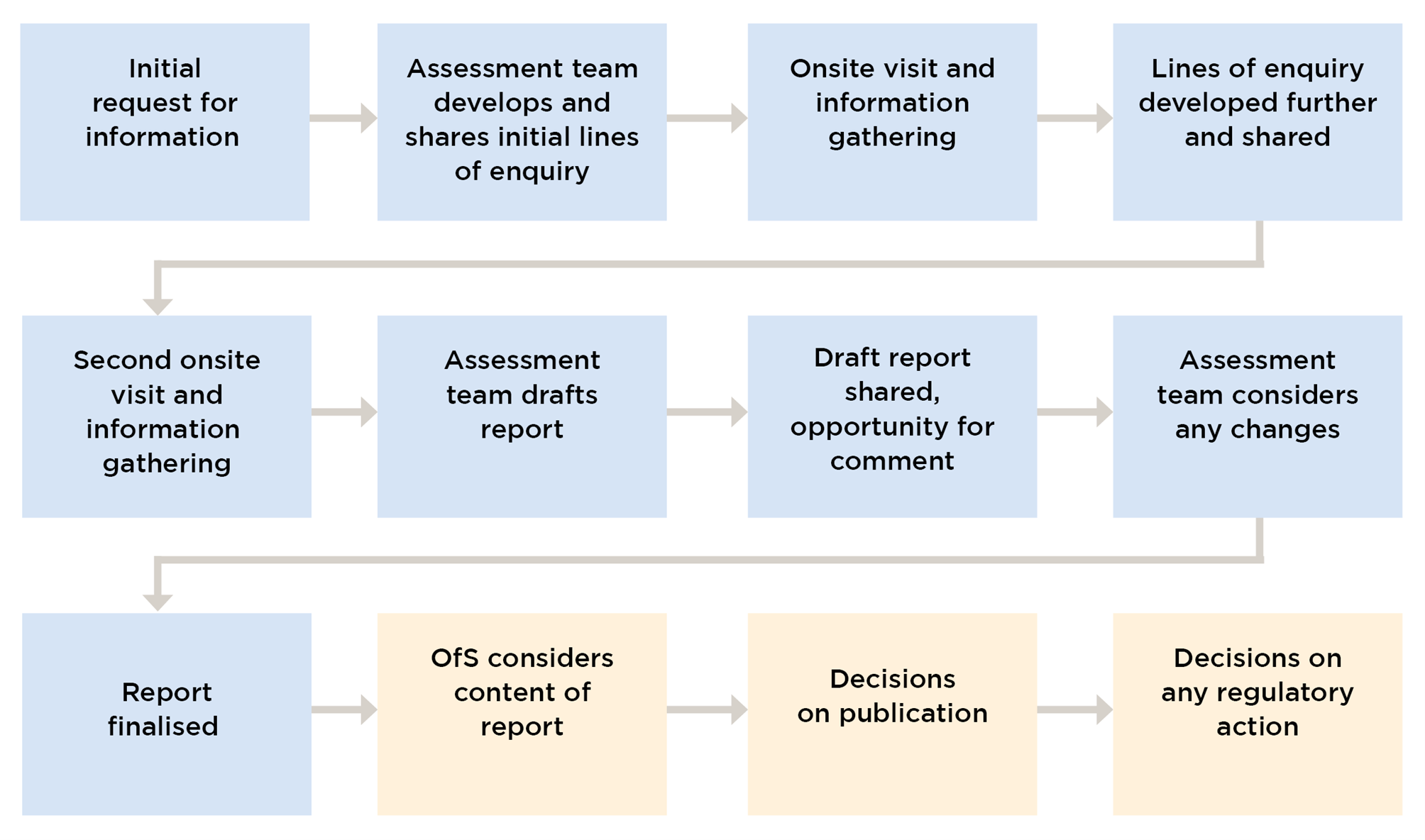

Figure 3 shows the process for the 2022-23 cycle of quality assessments. We are reviewing and developing this process, including to respond to the recommendations of the recent OfS Public Bodies Review and as a result of feedback from sector stakeholders.

Figure 3: Process for OfS quality assessments, 2022-23

Flow diagram showing the process for OfS quality assessments in 2022-23. It shows the following stages:

Initial request for information

Assessment team develops and shares initial lines of enquiry

Onsite visit and information gathering

Lines of enquiry developed further and shared

Second onsite visit and information gathering

Assessment team drafts report

Draft report shared, opportunity for comment

Assessment team considers any changes

Report finalised

OfS considers content of report

Decisions on publication

Decisions on any regulatory action

Assessment outcomes

Four assessments have now been closed because no quality concerns were identified. Where an assessment team did identify concerns, we are engaging with the institution and considering whether we should take further steps.

The assessment teams’ reports are advisory, and the decisions about whether the OfS intervenes to regulate a particular course are made separately.

Key findings from recent assessments

The 11 published reports from the 2022-23 cycle highlight four main areas that can affect the quality of higher education that students receive:

- delivery of courses and resources

- academic support and student engagement with courses

- assessment of learning

- academic leadership and oversight.

Delivery of courses and resources

Effectiveness of delivery and continued relevance of resources

The assessment reports highlighted some examples of effective teaching practice. These included encouraging students to share ideas, clear summaries of discussions that highlighted essential learning, and appropriate academic explanations of the subject.

However, the assessment teams also identified concerns, including that some institutions did not provide students with enough opportunities to interact with each other or to develop their ideas and knowledge. This had a negative impact on their engagement with their learning, their student experience, their grades and how many of them continued with the course. There were also occasions where course content was outdated or ineffectively delivered, for example delivery styles that were not engaging for students, or not enough explanation of the material on slides even when this was requested by students.

Variability in the skills of teaching staff and the use of associate lecturers

The reports include examples of robust and effective systems to ensure teaching staff had the knowledge and skills needed to design and deliver courses effectively, and to support them in developing their teaching practice. There were many examples of continuing professional development, relevant in-house training and support for staff. These included sharing good practice, sessions to challenge staff and develop teaching skills, and support for staff to achieve relevant qualifications. In some institutions, there were significant resources and support for staff in setting out expectations for course design and delivery.

However, some staff members were not sufficiently up to date in discipline-specific or teaching skills, or did not have adequate relevant academic experience. In some instances, modules with poorer outcomes were linked to associate lecturers.15 These staff generally had useful experience of working in relevant industries, but lacked the necessary teaching skills, and the quality of feedback they gave to students varied.

Where associate lecturers were fully included in staff development and training opportunities, there were more positive examples of their contributions to the effective delivery of courses.

Quality of the virtual learning environment

Where it was used well as part of an approach to learning, an institution’s virtual learning environment (VLE) was a core resource that enabled support to be easily accessed. However, the quality of resources varied. In positive examples, there was often an agreed approach to the use of the VLE, with content arranged in a clear and consistent way that helped students access what they needed, and clear oversight by senior staff to ensure this was applied in practice.

In some of the institutions assessed, concerns about VLEs included:

- module resources lacking signposting to learning materials or clear ways to support students to engage in independent study

- resources not covering the whole of the module content, or demonstrating the necessary subject depth and breadth

- inadequate engagement with appropriate academic literature, such as insufficient academic referencing on slides or insufficient content from relevant texts

- students being enrolled on modules too late to access the information they needed.

Suitability of the delivery model

Some reports reflected on the delivery models for the higher education courses, and particularly how well institutions understood their particular students and tailored course delivery effectively to meet their needs.

In some cases, information gathered during recruitment had shown that students would find it difficult to engage with timetabled sessions during a typical working week. Some institutions demonstrated how this had been considered in timetable design. For example, some had concentrated in-person teaching and supervision into longer blocks focused on specific days, rather than shorter sessions distributed throughout the week. In another example, teaching staff had a workload model that ensured they had enough time allocated to meet with all their students, but also that they could do this at flexible times that worked for students, including outside a typical working day.

However, in some institutions there was no indication that alternative approaches such as evening or weekend teaching had been considered, even where conventional teaching provision was a significant barrier to some students being able to engage with their studies. There were also examples of limited opportunities for students who did not attend in-person sessions to catch up on missed activities outside their classes.

Students highlighted how late changes to timetables, and a lack of flexibility about which seminar groups they could join, were particular challenges when balancing study with paid employment.

Points for universities and colleges to consider: Delivery of courses and resources

How do you ensure that:

- Course content remains up to date?

- Students are encouraged to interact in course delivery?

- All staff members are up to date in discipline-specific and teaching skills?

- VLE resources cover the whole of course content and effectively support independent learning?

- Courses are effectively delivered to meet the particular needs of your students?

Academic support and student engagement with courses

Capacity of staff and number of staff vacancies

The teams identified concerns relating to the capacity of existing staff, or the number of staff vacancies. Where staff had heavy workloads and there were many vacancies, this led to additional pressure on them with a direct negative impact on students.

For example, some courses had insufficient staff available to meet the advertised sessions with personal tutors or the expected deadlines for marking and feedback. One report noted that staff resource for student support on a course had not increased at the same rate as student numbers, leading to concerns about reduced capacity to support students effectively.

There were also positive examples of staff capacity and how it was used. These included:

- effective allocation of time for teaching staff to complete personal tutoring activity

- clear expectations of what personal tutoring activity should entail

- clear and robust processes to ensure sufficient staff resources were allocated to each module

- the opportunity to ensure that the particular interests of staff (including their research interests and expertise) could be considered in work allocation

- effective use of centralised support teams to support teaching staff, for instance in monitoring student engagement

- roles and responsibilities split across teaching staff and other support teams

- good record keeping and reporting that enabled information to be effectively shared.

Methods of monitoring student engagement and attainment

The institutions used various methods to gather information about how well students were engaging with their teaching and learning, and the outcomes of the assessments they were set. These included collecting data on access to VLEs, recording attendance data from in-person sessions, monitoring the submission of work and engagement with personal tutors, and tracking library usage. Some institutions used more than one of these, sometimes alongside other methods to look at a range of indicators.

In particular, the teams wanted to understand how institutions used information and indicators from this monitoring to identify students who might need additional support, and whether and how they then provided this support. Where institutions lacked established ways of gathering or (equally importantly) reviewing information, opportunities to intervene and offer support could not be identified.

There were, however, positive examples of central support and non-teaching staff playing a role in effectively monitoring and acting on student engagement information, often with teaching staff maintaining clear oversight. This included instances where relevant information was used to ensure students were more engaged with their courses, and evaluate the impact of different approaches to supporting them.

Several of the teams explored how institutions considered the ways their students were being supported to engage with study, and how information was used to ensure their needs were met in practice. They found positives examples of approaches to this issue, and of changes implemented after considering the needs of students. These included:

- specific support for students progressing from a foundation year

- changes to timetabling to better suit the student demographic

- specific staff roles with responsibility for identifying and actively contacting students who showed signs of starting to disengage from their learning.

However, at some institutions it was unclear how the information held about students and their needs was being considered.

Points for universities and colleges to consider: Academic support and student engagement with courses

How do you ensure that:

- There is sufficient staff capacity to deliver the courses as advertised?

- There is effective allocation of time for teaching staff to complete personal tutoring activity?

- There is effective monitoring of how engaged students are in their learning and how they are performing in assessments?

- There is effective use of this information to identify students who might need additional support and then provide it?

Assessment of learning

Rigour and consistency

Some teams explored the rigour and consistency of assessment, including how institutions ensured courses were testing relevant skills. Positive examples of approaches to this included:

- effective use of links to industry groups and employers

- techniques to ensure assessments were marked consistently

- effecting testing of processes to ensure consistency in marking (for example, marking teams meeting in advance to compare samples, or independent marking by two or more examiners)

- development of approaches involving a range of assessment types across the whole course, with well planned (for instance, staggered) timings.

However, the teams also identified concerns in this area. In one report, an inconsistent approach to assessment attempts meant that the way students were required to demonstrate knowledge and skills varied depending on when in the year they began the course. The number of assessment attempts allowed at this institution (without a clear pedagogic rationale) raised concerns about the rigour of the assessment and the level of challenge.

In another report, high volumes of non-technical assignments led to a concern about the effectiveness of assessment in a technical subject. In this example, the assessment type was not always an effective way to assess the relevant skills, or to provide stretch and rigour consistent with the level of the course. The criteria set for students to earn grades were too low and not rigorously applied. This led to concerns about students at this institution not being effectively assessed, and doubt about how far their qualifications could be trusted.

A further report identified concerns about students’ opportunities to receive feedback on drafts of their work before submitting it for assessment. This team also considered that too much teaching time was used to prepare students for assessments, including in some instances sharing exam questions in advance. These examples led to concerns about the academic integrity of assessment.

Feedback for students

Several teams looked at the feedback given to students, including formative feedback whereby students are given information after an assessment to help them improve their work, and may be given resubmission options.

There were examples where this was inadequate for some students, for instance where the basis on which marks were being awarded, and how these could be improved in the future, were not clear to students. In other instances students were not provided with feedback within agreed timelines, preventing them from learning from that feedback in time to apply it to their next assessment. In some cases, formative feedback was given in inadequate ways, sometimes being couched in inaccessible language or given only in the context of meetings rather than in written form.

The teams also reported on good practice in this area. This was often seen where student feedback was routinely provided in a variety of formats, including writing, voice notes, and videos. There were good examples of well planned timing meaning that students could get feedback on one assessment, module or study year before starting the next one. In some cases, staff oversaw the giving of feedback by agreed deadlines. This helped the delivery of consistent feedback in a timeframe that enabled students to make best use of it.

Support to avoid academic misconduct

Some concerns related to assessment feedback that lacked consistent information on avoiding academic misconduct such as plagiarism or collusion. Some students were not consistently directed to support that would help them understand and avoid misconduct in the future. There were examples of students not receiving consistent information even when policies and procedures identified ways they could access this kind of support. One team found students being encouraged to paraphrase content in their assessed work, to reduce a similarity score in software designed to identify plagiarism, rather than supporting them to improve their academic practice.

However, the teams also saw positive examples of this type of support. In a particular example, when teaching staff identified an issue such as the failure to reference a source, discussions were held with each student to make sure they understood what constituted plagiarism. The institution was able to show how this had led to a reduction in its occurrence.

Points for universities and colleges to consider: Assessment of learning

How do you ensure that:

- Formative feedback is timely and given in formats that students find useful?

- Assessment is appropriately rigorous and tests relevant skills?

- Links with industry contacts are used effectively to inform assessment approaches?

- Marking and assessment processes are tested to ensure consistency and rigour?

- Students are given consistent information on avoiding academic misconduct?

Academic leadership and oversight

Clarity in roles and responsibilities

Some assessment teams explored how responsibilities for student support were shared between teaching staff and their professional service colleagues. In some cases, there was no shared understanding about how such responsibilities were distributed, including responsibility for considering information about whether students were continuing to engage with their education. In one report, the team identified failings in educational leadership and academic governance that contributed to inadequate academic experiences for some students. This included poor oversight and management of quality.

Assessment teams found that clear specific roles, and clear responsibilities within them, together with oversight by senior staff, were more likely to lead to positive experiences and outcomes for students.

Revalidation processes and changes in approach

In the cases where the teams did not identify concerns about academic leadership and oversight, they often found that there had recently been an effective revalidation, or reapproval, process – a cyclical internal review of academic courses – informing changes in approach. Some institutions had already acted on relevant data and feedback to make improvements.

In one revalidation process, data had highlighted an issue with students’ levels of progress to employment or further study, and the institution then adopted a conscious and coordinated approach to ensuring the curriculum prepared students for employment. This included engaging with businesses to help ensure courses were up to date. Revalidation was used to ensure courses offered greater flexibility, efficiency and focus on the business practices students might expect to find at future employers. There was evidence of staff and students being involved and engaged in the revalidation process, which is likely to have had a positive impact on the outcomes.

In some cases, there had been review activity relating to courses and their delivery, but no evidence of how any issues identified had been addressed; in others, there was a lack of alignment between the review outcomes and subsequent plans and actions. In these instances, the teams were less likely to be assured of the effectiveness of the review activity. They were also less likely to find that outcomes from the review were having a positive impact on the quality of the courses or the experiences of students.

The teams noted positive examples relating to how feedback from students was used in practice. In particular, they saw specific examples where feedback had been gathered and institutions could demonstrate how they had considered it, whether they made changes as a result, and if not, why not. The teams were more likely to be reassured about how the student voice was considered when students had a good understanding of how their comments and feedback were taken into account, and when students felt listened and responded to (even when their suggestions were not implemented).

Points for universities and colleges to consider: Academic leadership and oversight

How do you ensure that:

- There is a clear shared understanding of staff roles and responsibilities on different courses?

- There are effective revalidation processes for your academic programmes that inform any subsequent changes in delivery?

- You continue to monitor risks to quality in between revalidation events?

- Student voices are adequately and appropriately included in any review of academic programmes?

Conclusion

Ensuring that quality remains high is a shared goal for universities and colleges and the OfS. It is essential to the reputation of higher education in England, to establishing equality of opportunity, and to the future of all the students undertaking these courses.

A central part of the OfS’s work is ensuring that students can be confident in the quality of courses across the higher education sector, and we are continuing to prioritise and develop our approach to regulation in this important area.

We are gathering views and feedback on the 2022-23 cycle of quality assessments and our approach to quality assessments in general, including how we select institutions for assessment. We will continue to engage with institutions and students as we develop our approach towards the integrated model set out in the OfS Public Bodies Review.

Our recent round of quality assessments, carried out by teams including experts from the sector itself, focused on a small number of courses in specific subjects, but the published reports identify common areas where risks to course quality can occur.

In the assessment reports we analysed, the main risks for delivery and resources include not keeping materials up to date, with a need for virtual learning environments in particular to be rigorous and thorough in their approach. Others are that teaching staff and lecturers may not be equipped to deliver courses to a consistently high standard, or that delivery models may not remain well suited to the students undertaking the course.

Also highlighted in the assessment reports were risks in terms of academic support and student engagement to avoid academic misconduct. Risks for oversight include a lack of clarity in staff roles and responsibilities, or of an effective revalidation process for courses.

We know that universities and colleges work assiduously to ensure that they provide a good education to their students, and we hope that the information in this brief, and the much greater detail given in the reports themselves, will be useful in fulfilling these essential aspects of that work. We expect to publish further information about any regulatory interventions that draw on the findings in these assessment reports.

Notes

- For the sake of readability in this brief we may use ‘universities and colleges’, or just ‘universities’ or ‘institutions’, to refer to what our regulatory framework and other more formal documents call ‘higher education providers’.

- See Gov.UK, ‘Fit for the future: Independent review of the Office for Students’, July 2024. The four priorities identified are the quality of higher education, the financial sustainability of higher education providers, protecting how public money is spent, and acting in the student interest.

- OfS, ‘Securing student success: Regulatory framework for higher education in England’ (OfS 2022.69), November 2022.

- For information on what it means for a university or college to register with the OfS, see OfS, ‘Registration with the OfS’. For information on degree awarding powers, see OfS, ‘Degree awarding powers’.

- OfS, ‘Quality assessments: Assessment reports’, last updated October 2024.

- OfS, ‘Securing student success: Regulatory framework for higher education in England’ (OfS 2022.69), November 2022, pp89-140.

- See OfS, ‘Business and management studies: Subjects in profile’ (2023.47), September 2023; OfS, ‘Computing: Subjects in profile’ (2023.61), November 2023.

- OfS, ‘Regulatory advice 15: Monitoring and intervention – Guidance for providers registered with the Office for Students’ (OfS 2020.60), last updated November 2022.

- For more information about the ‘B conditions’, see OfS, ‘Securing student success: Regulatory framework for higher education in England’ (OfS 2022.69), November 2022, pp89-140.

- See OfS, ‘National Student Survey’, last updated January 2024.

- If students, staff or members of the public believe that a university or college is not meeting regulatory requirements, they can send us a notification. See OfS, ‘Notifications’, last updated September 2023.

- See OfS, ‘How we regulate student outcomes: Assessment reports’, last updated July 2024.

- OfS, ‘Assessment reports’, last updated October 2024. We consider whether to publish each assessment report individually and engage with the institution in question about these considerations.

- See OfS, ‘National Student Survey’, last updated January 2024.

- This role varies between universities and colleges, but often refers to staff employed on a short- or fixed-term basis, or those who have less academic experience.

Describe your experience of using this website