Gravity assist: propelling higher education towards a brighter future

Last updated: 01 March 2021

Executive summary

The first national lockdown in March 2020 sparked a rush of activity in universities and colleges to transition from in-person teaching to online delivery. This was done at great speed under intense pressure. By the time this review was commissioned in June, there was already a wealth of expertise and innovative practice to explore.

This report attempts to capture the lessons from an extraordinary phase of change. We conducted 52 interviews with digital teaching and learning experts and higher education professionals from around the world, received 145 responses to our call for evidence and surveyed 1,285 students and 567 teachers.

What follows is built on a vast array of learning and expertise and we are grateful to all those who contributed. Most importantly it offers a roadmap for the future. The review establishes what we take as the essential components of successful digital teaching and learning, and recommends core practices that all universities and colleges can use to improve for the benefit of generations of students to come.

The report does not represent regulatory advice or guidance. Instead, we are focused on sharing what we have learned, supporting reflection, and prompting further action, research and exploration of the ideas presented here. It is independent from the Office for Students’ (OfS's) regulatory functions and the recommendations should not be interpreted as regulatory requirements.

Adapting under pressure

Universities and colleges across the country shifted at great speed, under great pressure, often into uncharted territory. 58 per cent of students and 47 per cent of teaching staff we polled had no experience of digital teaching and learning before the pandemic.[i] By December 2020, 92 per cent of students of students surveyed were learning either fully or mostly online.

Video seminars, live and recorded online lectures, and lecture slides covered the bulk of digital teaching, with students also taught in digital labs, placements, and online performance and portfolio reviews. But these broad categories only scratch the surface.

Case studies in this review highlight the innovation on show. Digitally simulated scenarios for paramedic training, science experiments conducted with remote-controlled lab equipment, online master classes for music students, digital exhibitions connecting final-year portfolio students with industry experts and employers, virtual writing cafés – the speed and scope of adaption was extraordinary.

Universities and colleges were also forced to address issues of digital access. Previous polling by the Office for Students (OfS) found students impacted by unreliable internet connections, lack of access to appropriate hardware and software, and unsuitable home study spaces.[ii] Universities responded in a range of ways. Some delivered 4G dongles to students and expanded existing laptop loan schemes for students in need. Other initiatives included making learning resources available on mobile apps and developing alternative modes of assessment.

What did staff and students say?

A range of polls and surveys have sought to capture student experience during the pandemic with varied results.[iii] Most students responding to our polling (67 per cent) told us they were content with their digital teaching. A similar proportion (61 per cent) said teaching was in line with their expectations, although 29 per cent said it was worse than expected. Almost half of students (48 per cent) said they were not asked for feedback on the teaching they have received.

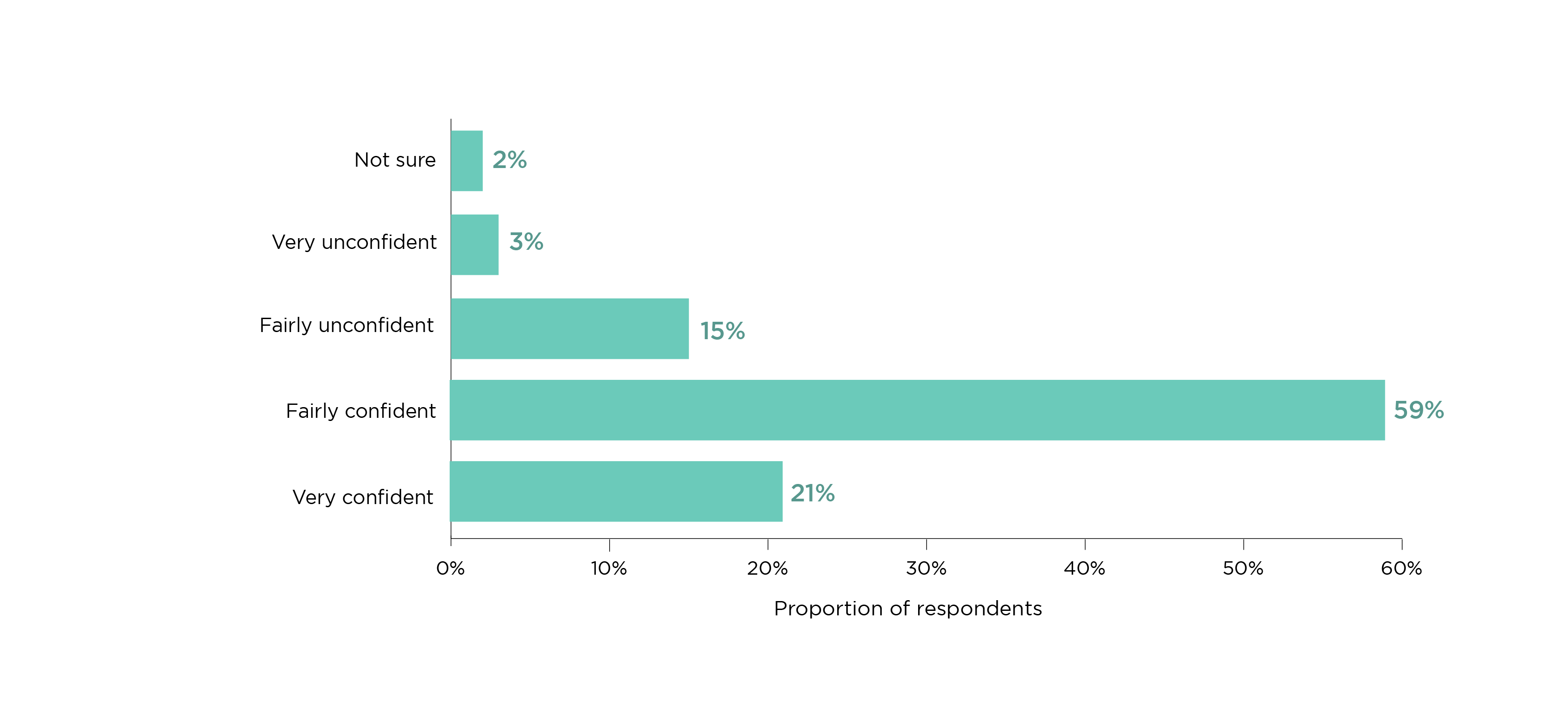

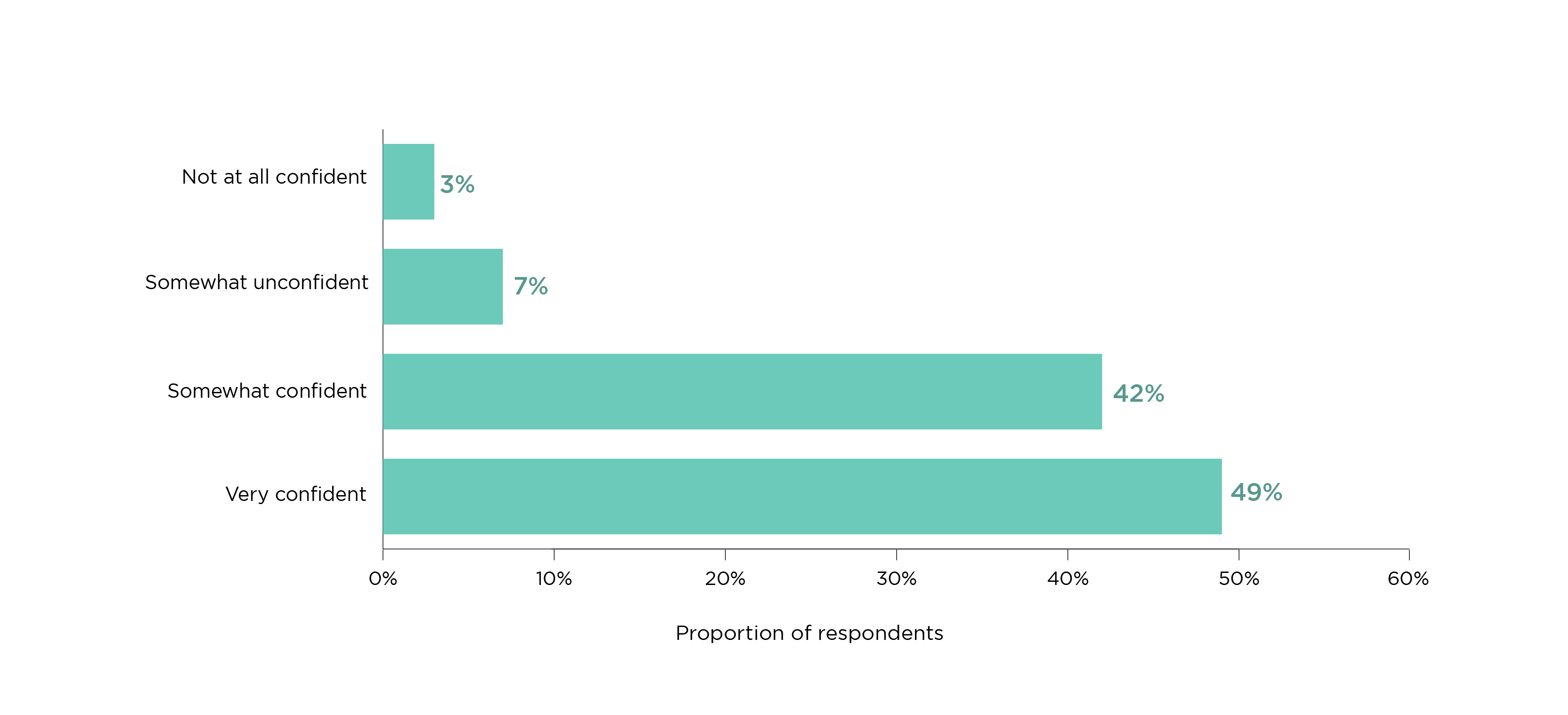

Polling also highlighted the need for increased support for teaching staff. Only 21 per cent of teachers said they were ‘very confident’ that they had the skills to design and deliver digital teaching and learning. Almost half of students (49 per cent) were very confident that they had the skills to benefit from online learning (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: How confident or not are you that you have the knowledge and skills necessary to design and deliver digital teaching and learning? (teaching staff)

Figure 2: How confident or not are you that you have the digital skills necessary to successfully engage with the digital teaching and learning you are receiving? (students)

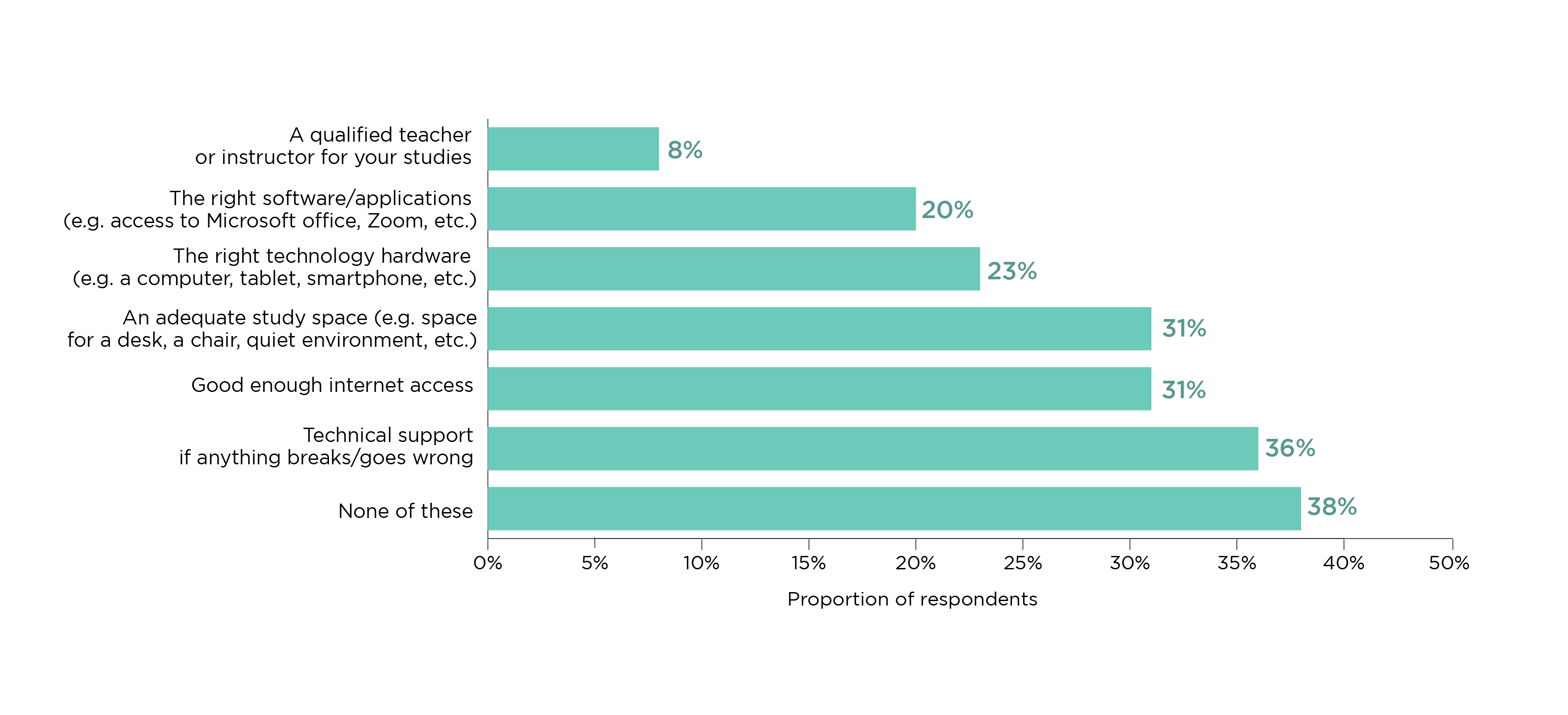

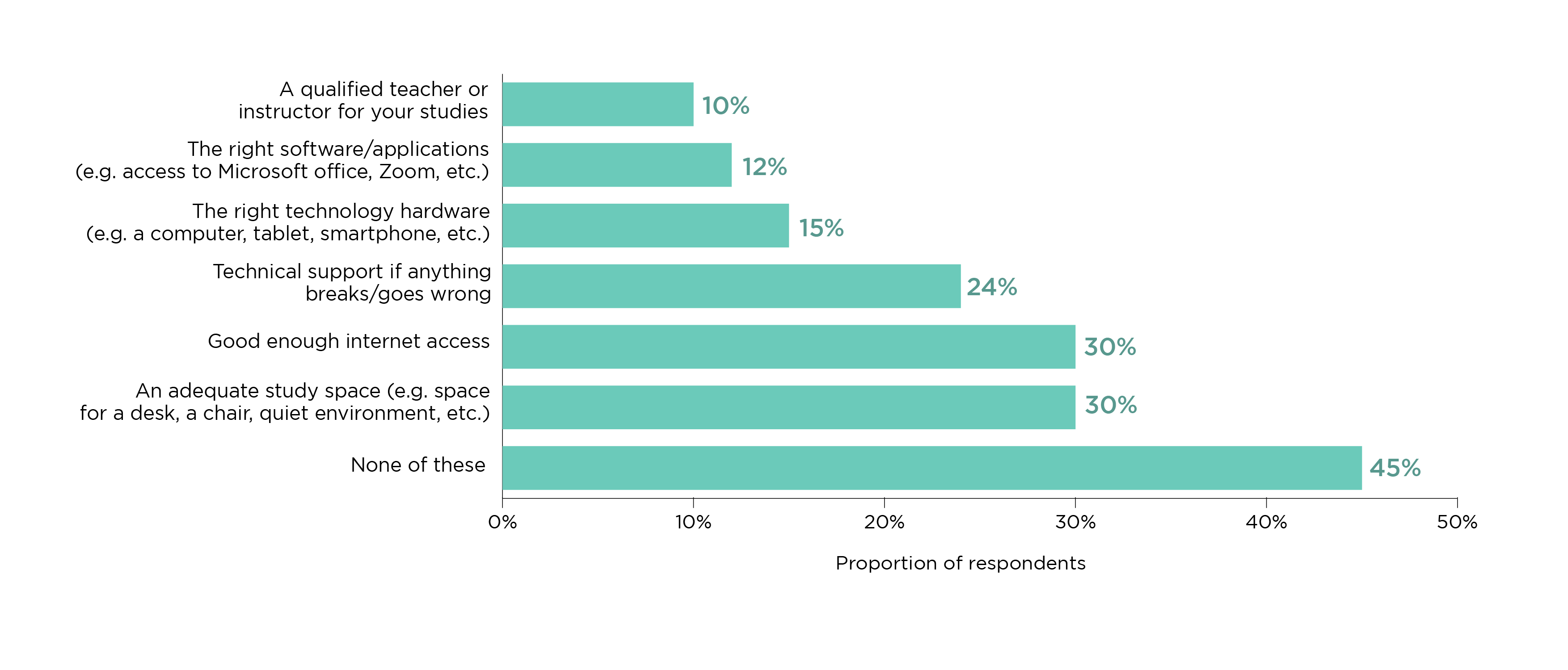

Over a third of teachers (36 per cent) reported having no access to technical support while teaching digitally, compared with under a quarter of students. And 23 per cent of teachers felt they lacked the right technology, compared with 15 per cent of students.

Figure 3: While delivering digital teaching and learning, have you been without access to any of the following? (Please select all that apply) (teaching staff)

Figure 4: While digitally learning this academic year, have you been without access to any of the following? (Please select all that apply) (students)

Seizing the opportunity

Professor Iain Martin, Deakin University (Australia)

‘Digital delivery will be the norm as the world moves to blending digital work and life with place-based activities.’

We heard this sentiment from Professor Martin repeated throughout the review. Despite the fraught circumstances of the pandemic, there was a consensus that innovation forced through lockdown may lead to lasting and positive change. Widespread digital teaching and learning is just not an emergency stopgap, but will have an important role in the future.

In a survey of international university leaders in May 2020, 55 per cent agreed that the experience of mass online teaching and the realisation of its possibilities will increase the use of fully online degrees at their institutions over the next five years.[iv] Our own polling found that 70 per cent of academic staff agree that digital teaching and learning provides opportunities to teach students in new and exciting ways.

Online teaching has a range of potential benefits, and in our research five broad positives stood out.

Five benefits of online learning:

- Increased flexibility.

- Personalised learning.

- Increased career prospects.

- Pedagogical opportunities.

- Global opportunities.

Several studies have compared in-person, online and blended courses, but there is little evidence that outcomes based on the mode of teaching differ significantly.[v] The effectiveness of a course is based on the approach to the design and the quality of teaching rather than just how it is delivered. Digital teaching and learning can have enormous benefits, but it must be done well.

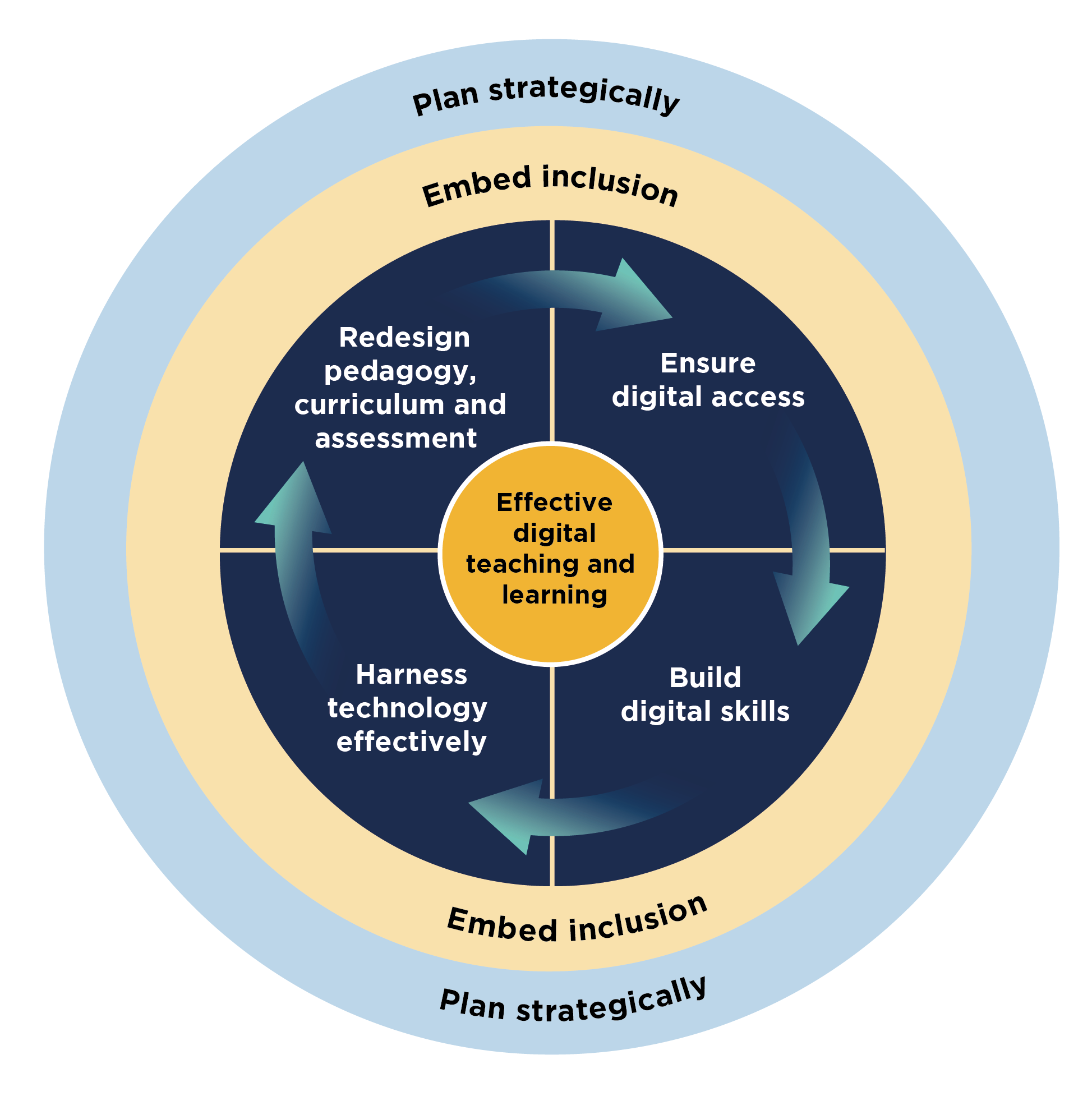

What does good digital teaching and learning look like? How can universities and colleges achieve it? Based on our review we have identified six core components of successful digital teaching and learning that educators can apply directly in their work.

Figure 5: The six components of successful digital teaching and learning

- Digital teaching must start with appropriately designed pedagogy, curriculum and assessment.

- Students must have access to the right digital infrastructure.

- Good access enables staff and students to build the digital skills necessary to engage.

- Technology can then be harnessed strategically, rather than in a piecemeal or reactive way, to drive educational experience and outcomes.

- Inclusion for different student groups must be embedded from the outset.

- All the elements need to be underpinned by a consistent strategy.

What does this model mean in practice?

Redesign pedagogy, curriculum and assessment

Technology cannot just be bolted onto existing teaching material. There needs to be a focus on how students learn. Instead of blunt attempts to replicate in-person settings, learning outcomes should drive how technology is used. For example, students said they benefited from round-the-clock access to resources ahead of taught sessions, like short instructional videos demonstrating lab techniques. When students then enter the lab, they already have an understanding and can use lab time more effectively.

Joanna MacDonnell, Director of Education and Students, University of Brighton

‘The blended learning delivery model has provided the opportunity to begin to design out traditional long monologue lectures, through emphasising the “chunking up” of delivered content in pre-recorded and live MS Teams lectures, and through face-to-face sessions being dedicated to practical work, seminars and small group teaching.’

High-quality courses need rigorous and fair assessment – this does not always have to mean invigilated written exams in lecture halls. Universities moved thousands of exams from in-person to online and we heard of many approaches: open-book exams with a prescribed timeframe, online timed assessments and assessments based on digital scenarios. More work needs to be done to develop scalable approaches, particularly in addressing potential risks around plagiarism and ensuring that sweeping changes to assessment methods do not bake in unwarranted grade inflation.

However, it is clear that digital assessment is not just consistent with the maintenance of rigorous standards and consistency over time; when it is done well it can actually enhance it. Where this happens, it is more important than ever that there is strong moderation to ensure the maintenance of standards and the integrity of assessment and qualifications.

Digital access

The shift to remote teaching meant students needed to work in family homes or shared accommodation, worsening issues around access to the equipment, infrastructure and space needed to engage in their studies. Around 30 per cent of the students we polled lacked good enough internet access, and 30 per cent did not have access to an adequate study space.

We propose a definition of digital access which combines the essential things all students need to benefit fully from digital teaching, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Definition of digital access

| Element |

Criteria | |

| Appropriate hardware |

Students have the hardware that allows them to effectively access all course content. Hardware is of the specification required to ensure that the student is not disadvantaged in relation to their peers. |

|

| Appropriate software | Students have the software they need to effectively access all aspects of course content. | |

| Robust technical infrastructure | Technical infrastructure and systems work seamlessly and are repaired promptly when needed. | |

| Reliable access to the internet |

Students have reliable and consistent access to an internet connection. Reliability and bandwidth of the internet connection are at a sufficient level for ensuring that a student is not disadvantaged in relation to their peers. |

|

| A trained teacher or instructor | Students have a trained teacher or instructor who is equipped to deliver high-quality digital teaching and learning. | |

| An appropriate study place | Students have consistent access to a quiet space that is appropriate for studying. | |

We saw a number of short-term fixes attempted during the pandemic. But to address digital poverty effectively, the higher education sector will need to develop systemic and long-term solutions.

Universities that have adapted well to digital and blended learning proactively assess students’ digital access on an individual basis. This means engaging with students before their courses start and offering practical solutions where necessary. This could involve loaning devices, offering financial support, or working with other local organisations to provide appropriate study space.

Jenny Coyle, Programme Leader of HNC and HND Acting and Musical Theatre, The City of Liverpool College University Centre

‘One case I experienced this year was with a BA student who didn't have access to a laptop nor wi-fi. She has a young daughter and could only really work after she had gone to bed. I worked with her using WhatsApp voice notes, which she performed some evaluative assessment on but also doing tutorials via phone […] Our final assessed tutorial was on a video call via WhatsApp, which was recorded audio and video. This student was close to giving up at the start of lockdown, but has walked away with a 1st Class BA Hons Degree.’

Small adaptations to the way digital teaching and learning is delivered can make a big difference. For example, resources can be designed so that students who have lower bandwidth connections can access all content, and offline alternatives made available.

Evidence suggests that school closures will widen educational attainment gaps and universities are increasingly sensitive to the impact of the pandemic on school learning and lower-income households.[vi] Delivering on digital access is likely to become a more important part of meeting ambitions to improve access and participation for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Build digital skills

Students are confident in their own digital skills – significantly more than staff, according to our polling. However, universities and colleges can still improve the support and training on offer for students.

For next year, universities and colleges will wish to consider how to communicate to students the digital skills they need before their courses begin, how to help build these skills on the courses, and develop mechanisms for students to track their skills progression. There is a wider opportunity to align skills with those that graduates might be expected to have in work. By regularly using digital technologies, students are already building skills that are likely to be useful in the jobs they have after graduating.

Andy Beggan, Dean of Digital Education, University of Lincoln

‘One anticipated change for art-based programmes is courses placing more emphasis on developing student digital and website development skills in preparation for more virtual performance and exhibitions.’

Staff need support too. Our polling found that 47 per cent of teachers had no experience of digital teaching and learning at the beginning of lockdown in March 2020. While staff grew more confident as the pandemic progressed, we often heard that their digital skill level could be a barrier to successful teaching.

Harness technology effectively

We often heard that the pandemic had highlighted inadequacies in digital infrastructure and that greater investment was needed.

The best technology meets the real-world pedagogical needs of teachers and helps deliver improved learning. However, students and staff suggested to us that overly complex systems or using too many digital platforms can be counterproductive.

Where possible, platforms can be streamlined into a seamless digital environment for students and staff. Ideally, this should be combined with regular training and opportunities for students to build skills – as well as considerations of how accessible virtual platforms are to different student groups.

Several areas promise exciting developments, including augmented and virtual reality and data analytics. Capitalising on these opportunities needs collaboration between higher education providers and technology companies, meaningful consultation with staff and students, and a culture that is open to change.

Embed inclusion

While the flexibility of online learning can open up higher education to more students, there are risks, which may cause some to feel excluded from digital communities. It is critical that universities build inclusivity into their overall approach.

Advance HE

‘Whilst everyone is getting more used to communicating in an online environment, it is more challenging for an educator to “read the room” and pick up non-verbal cues that demonstrate understanding or misunderstanding; this has many potential consequences but can be particularly challenging for disabled students or across different cultures.’

The pandemic highlighted a number of benefits relating to inclusion, with broad agreement that some students who did not previously feel able to fully contribute are significantly more engaged. For example, chat functions enabled more questions than in-person settings.

There are three broad stages to embedding inclusion systematically:

- Review and evaluate – engaging with different student groups and proactively seeking feedback are essential.

- Design inclusively – those designing online platforms should have a clear understanding of the needs of teachers and different student groups.

- Adapt safeguarding practices – there must be robust mechanisms to report and deal with online harassment and other forms of hate crime.

Plan strategically

High-quality digital teaching and learning requires significant investment, for example in staff training, buying equipment, staff time to develop resources, and updating old platforms. While substantive, these costs should be seen in the context of the potential benefits they bring. Done well, digital teaching and learning can improve learning outcomes, enhance student engagement and perceptions of value, and build resilience in the face of future shocks.

Recommendations

We have condensed the lessons from our review into a set of recommendations that we believe leads to high-quality digital teaching and learning. To help make these recommendations practical, we have drawn out six things we think every university or college leader should consider ahead of the 2021-22 academic year. The overarching recommendations, which we hope will remain relevant for years to come, follow this highly practical set of prompts to aid leaders as they approach the coming year.

Table 2: Recommendations

- Design teaching and learning specifically for digital delivery using a ‘pedagogy-first’ approach.

- Co-design digital teaching and learning with students at every point in the design process.

- Seize the opportunity to reconsider how assessments align with intended learning outcomes.

- Proactively assess students’ digital access on an individual basis and develop personalised action plans to mitigate any issues identified.

- Build learning and procure technology around the digital access actually available to students, not the access they would have in a perfect world.

- Communicate clearly to students the digital skills they need for their course, ideally before their course starts.

- Create mechanisms that allow students to track their digital skills throughout their course and allow these skills to be recognised and showcased to employers.

- Support staff to develop digital skills by incentivising excellence and continuous improvement.

- Streamline technology for digital teaching and learning and use it consistently as far as possible.

- Involve students and staff in decisions about the digital infrastructure that will be used and how it will be implemented.

- Foster a culture of openness to change and encourage calculated risk-taking.

- Review and evaluate whether provision is inclusive and accessible.

- Design inclusively, build a sense of belonging and complement this with tailored support for individual students.

- Adapt safeguarding practices for the digital environment.

- Ensure a strong student voice informs every aspect of strategic planning.

- Embed a commitment to high-quality digital teaching and learning in every part of the organisation.

- Proactively reflect on the approach to the digital and physical campuses.

Notes

[i] Full results of the polling are available in the main report, in Annex B. All further references to polling conducted for this review are to this.

[ii] The Office for Students, 2020, ‘‘Digital poverty’ risks leaving students behind’, available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/digital-poverty-risks-leaving-students-behind/

[iii] See: Office for Students, 2020, ‘What students are telling us during lockdown’, available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/blog/what-students-are-telling-us-about-learning-during-lockdown/; and Times Higher Education, 2021, Digital Teaching Survey. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/times-higher-educations-digital-teaching-survey-results

[iv] Times Higher Education, 2020, ’THE leaders survey: will Covid-19 leave universities in intensive care?’ Available at https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/leaders-survey-will-covid-19-leave-universities-intensive-care.

[v] Veletsianos G, 2020, ‘Learning online, the student experience’, John Hopkins University Press; Education Endowment Foundation, 2020, ‘Remote learning, rapid evidence assessment. Available at https://studyclerk.com/blog/evidence-on-supporting-students-to-learn-remotely; Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Bakia M, Jones K, 2009, ‘Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies’, U.S. Department of Education. Available at https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED505824; Arizona State University Foundation and The Boston Consulting Group, 2018, ‘Making digital learning work: success strategies from six leading universities and community colleges'. Available at https://edplus.asu.edu/sites/default/files/BCG-Making-Digital-Learning-Work-Apr-2018%20.pdf (PDF).

[vi] Education Endowment Foundation, 2021, ‘Best evidence on impact of school closure in the attainment gap'. Available at https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/guidance-for-teachers/covid-19-resources/best-evidence-on-impact-of-covid-19-on-pupil-attainment

Describe your experience of using this website