Navigating financial challenges in higher education

Financial data from universities and colleges in England suggests that the higher education sector is facing considerable financial pressure. Many have predicted reduced financial health, and these predictions are often based on aspirations for growth that analysis suggests is unrealistic.

This brief looks at the financial challenges facing universities and colleges, and the actions some are taking to navigate them, especially to avoid the risk to students of unplanned closure. It encourages leadership teams to continue to evaluate risks realistically, to plan ahead for financial challenges and to contact us if these arise. It does not constitute legal or regulatory advice.

- Date:

- 16 May 2024

Read the brief

Download the Insight brief as a PDF

Get the data

Download the Insight brief data

Read the Insight brief online

Introduction

The higher education sector in England is facing increasing financial challenges. Despite their diversity, which ranges from large universities and colleges to small specialist institutions, this year many more English higher education providers have predicted deficits and low operating cashflow in the near future.1

While net liquidity has fallen, there is evidence of the sector adjusting to protect its cash flow in the face of financial challenges. Some institutions are taking, and others may have to take, decisive action to remain financially sound. While this is happening, universities and colleges, and the Office for Students (OfS) as their regulator, must work to ensure that the interests of students continue to be protected.

This Insight brief outlines the main financial risks facing the sector, and shares examples of successful and unsuccessful steps universities and colleges have taken to respond to financial difficulties. This is based on our analysis of the latest annual financial returns from universities and colleges, and the intelligence we have gathered in 2023 and 2024 to date. It also explains the OfS’s regulatory role in relation to these issues.

We recognise that financial challenges and their impact, and the steps universities and colleges must take to mitigate them, will vary significantly between institutions. We invite higher education leaders and governing bodies to consider this brief, alongside our annual report on financial sustainability, within their own contexts as part of their own strategic and financial planning. We hope that it can contribute to, and where appropriate act as a launchpad for, conversations about improving financial planning.

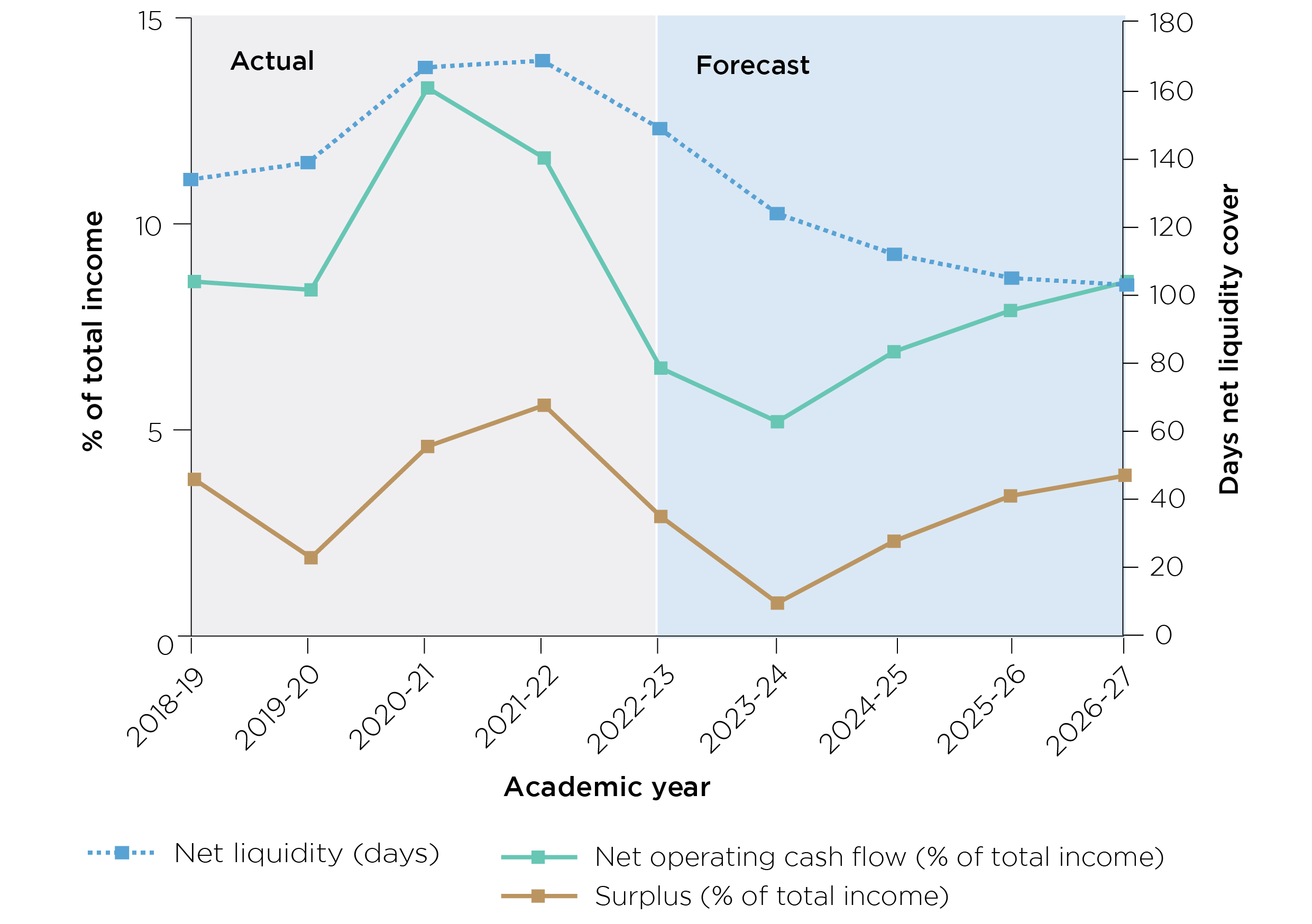

Shifting finances in English higher education

Our analysis of the latest annual financial returns submitted by universities and colleges shows that the overall financial performance of the higher education sector in England is weaker than in the past.2 Figure 1, showing actual and forecast financial performance from 2018-19 to 2026-27, illustrates this. There is considerable variation in the financial positions of individual institutions.

Figure 1: Actual and forecast financial performance, 2018-19 to 2026-27

Figure 1 is a line chart that shows the actual and forecast financial performance of higher education providers from 2018-19 to 2026-27.

There are three lines, which show the percentage of total income and days net liquidity cover. The net operating cash flow (percentage of total income) is shown by a solid green line. The surplus (percentage of total income) is shown by a solid orange line. The net liquidity (days) is shown by a blue dotted line.

The x-axis shows the academic year from 2018-19 to 2026-27. It is split into actual and forecast at the mid point, 2022-23.

The left-hand y-axis displays the percentage of total income between 0 and 15 per cent.

The right-hand y-axis displays the days net liquidity cover between 0 and 180 days.

Source: OfS annual financial return.

Overall, net operating cash flow (the amount of cash income compared with cash expenditure) fell from £4,795 million (11.6 per cent of income) in 2021-22 to £2,907 million (6.5 per cent of income) in 2022-23. Overall surplus levels (an institution’s ability to generate income above its accounting costs) fell for the sector as a whole from £2,290 million (5.6 per cent of income) in 2021-22 to £1,284 million (2.9 per cent of income) in 2023-24.3 Net liquidity across the sector (short-term cash available at the end of the year) fell from £16,709 million in 2021-22 to £16,506 million in 2022-23.

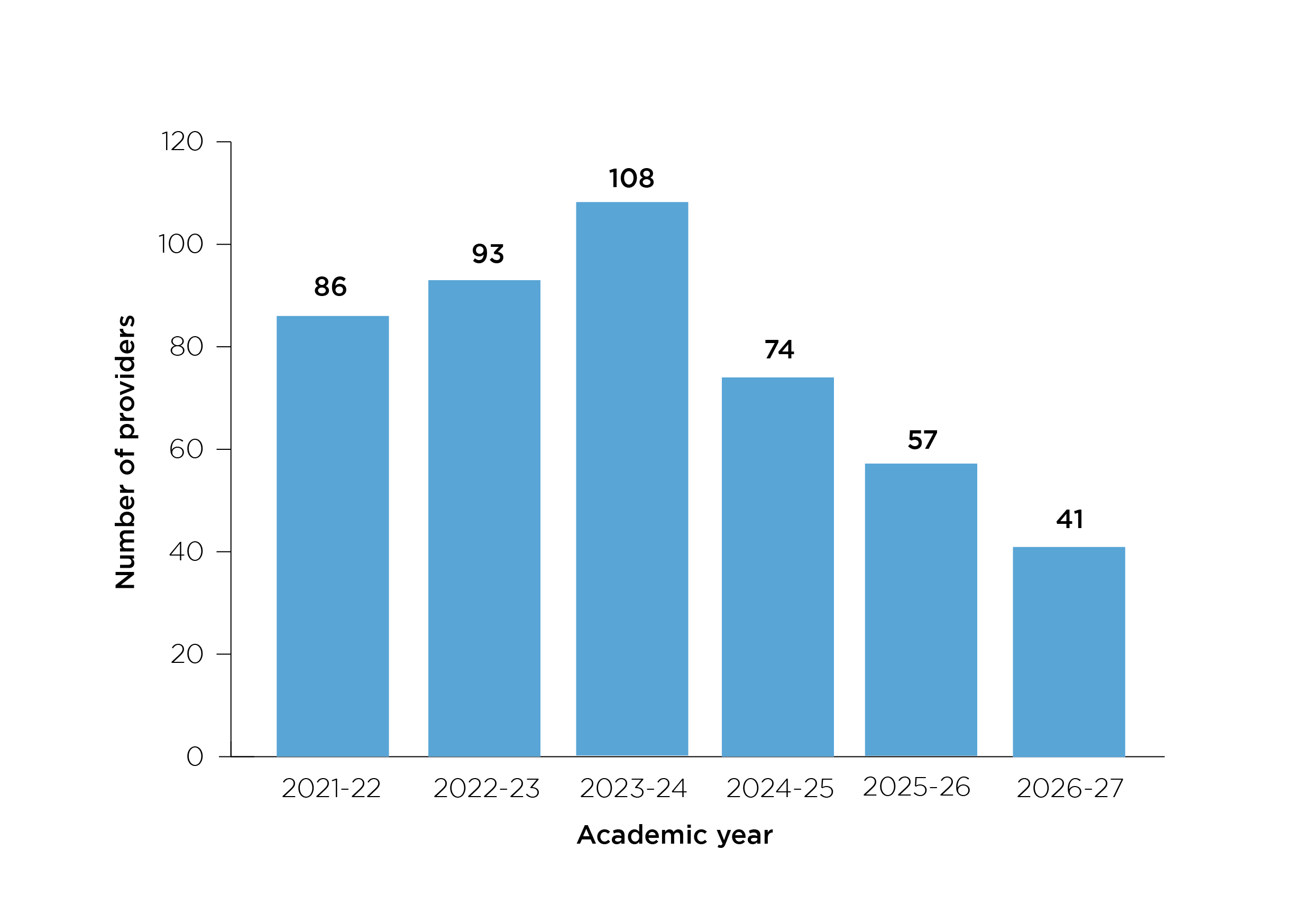

In aggregate, universities and colleges predict that their financial performance will become weaker still in the short term, before making a slower recovery than previously expected towards 2027-28. Sector averages do not tell the whole story, and there is considerable variability at the level of individual universities and colleges. In 2022-23, 93 higher education providers reported a deficit (with expenditure exceeding income). Based on their forecasts, this figure will be 108 in 2023-24, 74 in 2024-25, and 57 in 2025-26. Figure 2 illustrates this.

A deficit means that there is not enough income to cover expenditure. While this is generally manageable for most providers for short periods of time, ongoing deficits are not sustainable for the longer term.

Figure 2: Number of providers reporting deficits, 2021-22 to 2026-27

Figure 2 is a bar chart that shows the number of providers reporting deficits from the academic year 2021-22 to 2026-27.

There are six bars representing academic years 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-24, 2024-25, 2025-26 and 2026-27.

The x-axis shows the academic year from 2021-22 to 2026-27.

The y-axis displays the number of providers from 0 to 120.

Source: OfS annual financial return.

Overall, universities and colleges forecast that their income will rise by £10 billion over the next four years, and this is what supports their expectations of gradually improving financial performance. However, these income predictions are underpinned by plans to increase student recruitment significantly. In our view, based on latest trends in recruitment, these plans are likely to be unrealistic for many institutions.

Course fees from students represent the largest proportion of the income of most universities and colleges. Fees from international students can be a particularly important element of this, as the undergraduate tuition fee limit applies only to UK undergraduates.4 It is therefore impossible to forecast financial performance reliably without understanding and objectively forecasting any changes in this income.

Universities and colleges overall forecast annual increases of between 3.5 and 8.4 per cent from 2023-24 to 2026-27 in new UK students, and between 1.9 and 8.7 per cent in new EU students. For new non-EU students, the sector overall predicts annual increases of between 4.4 and 15.7 per cent over this forecast period. Our analysis indicates that, overall, these ambitions for growth in student numbers are not realistic.

UCAS data for 2023-24 tells a contrasting story, suggesting a slight but continuing downward trend in numbers of UK and EU undergraduate applications. Home Office data shows that overall numbers of visa applications for higher education are also reducing.5 Individual universities and colleges may be able to boost their share of these numbers through increased recruitment, but the trend of overall decline strongly suggests that the majority will not.

It is important to note that any changes in immigration policy could increase uncertainty and affect the reliability of forecasts in relation to the future recruitment of international students.

It is essential, particularly where a university’s sustainability is predicated on a growth in student numbers, that it has contingency plans to protect its sustainability and its students if forecasts of income from student course fees are not achieved.

Key financial challenges

The key financial challenges facing the sector, now and in the imminent future, include the following.6

- Declining value of UK undergraduate student fees. Tuition fees for UK-domiciled students at English universities and colleges were capped in 2017 at £9,250 for full-time undergraduates and £6,935 for part-time undergraduates. Inflation, particularly in recent years, has meant that the value in real terms of these tuition fees has declined significantly relative to institutions’ costs, and continues to decline, producing an ongoing significant challenge for universities and colleges. We calculate that in real terms, applying the Retail Price Index rates, the value of tuition fees in 2024 is approximately 31 per cent lower than it was in 2015.7

- Overreliance on international student fees. In response to the declining value in real terms of tuition fees from UK undergraduates, many universities and colleges are increasingly reliant on the higher fees they can charge international students. We have seen this risk develop, as recent data has shown that the numbers of new students from some countries can vary from year to year, with a volatility that can be difficult to predict. In May 2023 we wrote to universities and colleges with particularly significant recruitment of students from China, to ensure they have contingency plans in case these numbers fall.

- Decline in applications. The number of undergraduate applications from UK students has marginally declined, despite an increase in the number of 18-year-olds in the population.8 There also appears to have been a recent and significant decline in the number of international applications for study visas, after very strong growth in recent years. This decline is more significant for certain countries.9

- Inflationary and other economic pressures. It is increasingly expensive to deliver higher education courses and research, because of rises in the cost of living. Operating costs are increasing, including for staff pay, student support services, energy, marketing, and back office functions. It is also increasingly expensive to maintain buildings and embark on new building work.

- Reduction in capital spending. Overall, universities and colleges have been spending less on infrastructure, facilities, and equipment, to protect their cash reserves and limit large-scale new borrowing. However, this could result in a deterioration in the condition of buildings and facilities, meaning universities and colleges will need to spend more to maintain them in the future. Similarly, IT equipment and systems could become obsolete, needing additional outlay to ensure adequate provision of digital services.

- Cost of reducing carbon emissions. Reducing carbon emissions and achieving net zero emissions as soon as possible are priorities for many universities and colleges. However, the financial investments needed to achieve these important objectives are significant, and likely to be unaffordable in the present economic environment.

Navigating financial challenges

Universities and colleges are autonomous institutions, responsible for managing their own financial sustainability.10 In recent years, as in many other sectors, higher education providers have managed significant and multiple financial challenges. Throughout this period, the sector has responded by strengthening student recruitment, protecting its liquidity position and maintaining its strong asset base. While there is variation across providers, at the end of 2022-23, many had maintained a focus on sustaining cash reserves and their asset base in the face of further financial challenges.

There is a pattern across the sector of institutions deciding to continue to protect their liquidity through measures such as reducing spending on estates and other discretionary areas. A focus on cash management may help with short-term resilience but, in the longer term, more significant mitigating action is likely to be required.

This could involve rethinking an institution’s business model, for example rebalancing the resources spent on teaching and research, phasing out some courses, or seeking to recruit different students to different types of course. We know that some universities and colleges are actively exploring these options, and others have already embarked on significant change. While this is challenging, it is right that universities and colleges take early action to secure longer-term sustainability. As the operating environment for universities and colleges is becoming more constrained and competitive a ‘wait and see’ approach, relying on routine adjustments to make savings or increase income, is becoming less effective.

It is important that institutions and their governing bodies are working with credible financial approaches, including contingency planning, stress-testing (analysis to explore how financial health would be affected by particular events or situations), and modelling of realistic worst-case scenarios.

The most important message from our analysis, and our own sensitivity modelling on the finances of providers, is that universities and colleges should avoid relying on unrealistic predictions about growth in student numbers. They should robustly interrogate worst-case financial scenarios and should have viable contingency plans in place in case these scenarios materialise.

The challenging financial environment also means that it is more important than ever that any institution facing financial difficulties contacts us promptly, so that we can work together to protect students’ interests as it works to address its sustainability challenges.

In the box below, we look at some of the approaches to financial planning adopted by universities and colleges and share some of the scenarios we have seen during our engagement with them. We have grouped these under three headings: management and governance; financial and strategic oversight; and working and communicating with external organisations.

Management and governance

Our work with universities and colleges on financial sustainability shows the importance of strong governance, to provide scrutiny and challenge on financial matters. It highlights that management teams and governing bodies need to have members with the right skills and experience to ensure effective financial oversight. They should be familiar with the OfS’s role and responsibilities as regulator, as well as their own as directors and trustees, and conduct regular reviews of their effectiveness.

We have worked with some institutions where governing bodies have not fully understood the risks associated with implementing their approach to addressing financial difficulties. In other institutions, governing bodies have failed to recognise or respond to particular financial challenges until a very late stage, or only when prompted by the arrival of new senior leaders. This delay in understanding and confronting the financial situation has meant that the range of available options to mitigate risk was reduced or delayed.

We have also seen positive examples where universities and colleges have taken effective steps to review the size and composition of their governing bodies, to ensure that decisions can be made effectively and with appropriate student input. There have been instances where governors have been effective in pushing institutions to conduct stress testing of their business models and to set out detailed mitigations to address financial weaknesses.

Financial and strategic oversight

Our interactions with universities and colleges have reinforced the importance of having effective mechanisms for financial oversight. This includes having effective management information systems that deliver detailed, reliable and timely information, on which to base key strategic and financial management decisions.

We have engaged with institutions where leaders did not have a detailed understanding of which of their activities made a surplus and which a loss. This has meant that they have been unable to describe their financial situation in sufficient detail to reassure us that they have a compelling financial improvement strategy.

We have also had contact with institutions that engage in robust and proactive replanning in response to their analysis of financial risks. Sharing these strategy updates with their governing bodies has enabled them to make early decisions, before any serious risks materialise. To avoid the need for more extreme contingencies, such as having to close a campus or even cease higher education provision altogether, some institutions have been taking early decisive action.

Our contact with universities and colleges has also highlighted the importance of carrying out robust planning for market exit as part of their normal activities.

Working and communicating with external organisations

It is important for universities and colleges to have strong, proactive communication and engagement with the OfS and with external partners, for example banks, funders and other academic and non-academic partners. This includes early conversations with banks and other lenders about renegotiating any borrowing, and recognising that lenders may be more risk-averse than in the past.

We have seen examples of institutions incorrectly assuming, on the basis of previous experience, that renegotiating lending will be straightforward and quick, only to find that this is no longer the case. In these situations, institutions have not had effective contingency plans in place to accommodate delays or negative lending decisions. More often we see institutions discussing lending and potential covenant breaches at an early stage with their banks, but in the current challenging financial circumstances the lead times for this engagement need to be longer.

We have also seen examples of institutions failing to ensure that their financial advisers can meet their requirements (both internal and external) and have the relevant sector experience. This means that such advice may be delayed or inadequate, potentially understating the risks to an institution’s financial sustainability.

Where universities and colleges are considering changes to secure their financial sustainability, they should consider their continued compliance with the OfS’s regulatory requirements, including maintaining high quality course delivery and protecting students’ interests. They must also ensure their ongoing compliance with consumer protection law.

Where changes are made to the design and delivery of a course, the resources available to students, or their range of course options, the course should remain as it was originally advertised to students, with any disruption minimised and clearly communicated.11

We have seen an increase over the past four years in the prevalence of subcontracting courses for delivery by other higher education providers (also known as ‘franchising’). Some universities and colleges have increasingly adopted this approach to generate income to support their financial positions. This business model presents greater risk to students and taxpayers, because of the arm’s length nature of delivery and the financial drivers that are often present for both partners.

This means that governing bodies need to ensure that they have effective control over the operation of their partnerships. This includes effective oversight of student recruitment, the quality of teaching, attendance monitoring, and the quality of the data submitted by the delivery partner to the university. Weaknesses in these areas can be particularly acute where significant growth occurs without sufficient time to ensure that arrangements for oversight have been fully embedded.

Again, universities and colleges should consider their students’ needs and ensure they comply with our regulatory requirements in relation to courses delivered through partnerships. Courses must be of high quality and effectively delivered, with the lead provider retaining responsibility for ensuring that regulatory requirements are met.12 A future OfS Insight brief will explore subcontractual provision in further depth.

Working with the OfS

We listen to, and work with, universities and colleges to understand the challenges they are facing. We hold financial sustainability roundtables with finance directors from representative groups of institutions, to help us understand broad themes and risks and the type of steps they are taking in response.

We regularly discuss financial sustainability with individual institutions, we encourage them to act to secure their sustainability and protect students’ interests, and we strongly encourage them to seek our engagement early if they are concerned.

Early contact in such instances enables the OfS to prepare for any risk and support the university or college to take steps to protect students’ interests. This ensures that the university or college complies with its obligations, whether it manages to address its financial issues or instead faces closure. We can support the institution’s students by cooperating to stress test market exit plans to mitigate disruption, or helping to communicate changes to their learning environment.

Where a particular institution’s annual financial return, or the issues it reports to us, mean we have concerns about financial risk, we engage with its leadership team. Where a university is facing more acute financial challenges, our engagement is likely to increase to make sure we understand its circumstances in detail, and to ensure it takes appropriate action to protect students’ interests if closure becomes more likely.13

The annual financial returns we see from each registered provider give us a rich understanding of the financial health of the sector. Drawing on these returns, and other data and information, we publish annual reports on the financial sustainability of the sector, the latest of which is published alongside this Insight brief.14 The data and intelligence we gather help us identify key financial risks, across the sector and for different types of higher education provider, and to act as expert advisers to the government on the higher education sector’s financial health.

Protecting students in the event of university closure

Students make a considerable investment in their studies, in terms of both time and money, and our regulation is designed to protect this investment. The current financial climate could mean that some universities and colleges face closure and, in such cases, the OfS may act to protect students’ interests.

Given the significant impact closure of a university would have on students, we would want to see all governing bodies considering risks to students as part of their ongoing financial management, and identifying the actions they would take to mitigate those risks. This applies particularly to risks that might lead to what is known as a ‘disorderly market exit’ – the unplanned closure of a university, perhaps in the middle of an academic year, without arrangements in place to support students to complete their courses. Universities and colleges are responsible for, and should be considering at an early stage, the steps they would need to take to enable students to do this.

We are able to issue a ‘student protection direction’ to an institution that we consider to be at material risk of stopping its higher education provision within the next 12 months – this is set out in condition C4 in our regulatory framework. Since introducing this condition, we have imposed six student protection directions that seek to protect students as far as possible from the consequences of a disorderly exit.15

A student protection direction involves requiring the university to take specific steps to ensure that effective and actionable student protection plans are in place, or to produce a detailed market exit plan, relating to the possibility of its closing completely. The types of things we may require of an institution could include:

- Mapping its courses against those of other institutions, to identify a plausible list of universities and colleges that could accept its students.

- Engaging with alternative higher education providers to make ‘in principle’ agreements for students to continue their studies elsewhere.

- Engaging with the university that validates its degrees, to confirm plans for students to complete their courses with the validator.

- Preparing student records, and having the necessary systems and resources to generate certificates and transcripts of study, to ensure that students can receive an individualised package of evidence of their academic achievement.16

Given the scale of the work needed to mitigate the impact on students if their institution closes, we would encourage leadership teams in universities and colleges to consider these issues even if they are not currently concerned about significant financial risk. The steps suggested above are not trivial, and require considerable planning resource to achieve. However, considering what effective student protection would entail as part of routine financial planning can mean a university is well prepared to expand and escalate that work should it become necessary.

We have published examples of cases on our website where institutions have been at risk of closing their higher education provision, including one case where this eventually happened. These set out the key issues, the OfS’s approach, and the legislative basis for our actions.17

Conclusion

Universities and colleges are autonomous institutions and manage their own finances. The sector has generally shown resilience in the face of challenges in recent years. Nevertheless, it is extremely important to their students that they maintain high quality courses and deliver the higher education experience that they promised when students made their application. To achieve this an institution must remain financially sustainable. Any risk to sustainability is likely to affect the experience of students, which in turn may affect future student recruitment and worsen its longer-term prospects.

At present universities and colleges are faced with significant financial challenges, and some will need to take, or are already taking, bold actions to remain financially sustainable. Predictions of growth in student numbers, to increase income from course fees, are unlikely to be realistic for most institutions. Since many institutions’ financial plans rely on such forecasts, it is essential that governing bodies challenge the credibility of financial plans and consider whether their business model is sustainable over the long term.

We encourage leadership teams in universities and colleges, and members of their governing bodies, to consider whether their approach to strategic and financial planning is sufficiently robust for the current operating environment. Approaches that worked well in more financially stable times may not be effective in the face of current pressures. We encourage institutions to engage with us as soon as they identify financial challenges, so that we can work together to ensure that the interests of their students continue to be protected.

Notes

-

For the sake of readability in this brief we may use ‘universities and colleges’, or just ‘institutions’, to refer to what our regulatory framework and other more formal documents call ‘higher education providers’. Further education colleges are regulated by the Education and Skills Funding Agency. They are excluded from the data examined in this brief and have different arrangements for where these providers face financial challenges. Where we refer to ‘universities and colleges' in this document, we are not referring to further education colleges. universities and colleges.

-

Information for this section on ‘Shifting finances in English higher education’ is from OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024. Our analysis covers the period from August 2020 to November 2027. The analysis is based on the latest financial data submitted to the OfS by universities and colleges as well as other relevant data. This data excludes further education colleges, because their financial sustainability is overseen by the Education and Skills Funding Council.

- Surplus (or deficit) is total income less total expenditure, excluding other gains or losses (from investments and fixed asset disposals), the share of surplus or deficit in joint ventures and associates, and changes to pension provisions.

- Fees have been capped at £9,250 for UK full-time undergraduates and £6,935 UK part-time undergraduates since 2017. For more detailed information about the fees universities and colleges can charge UK undergraduates, see OfS, ‘Value for money as a student’, last updated June 2023.

- OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024.

- For more detail see OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024.

- OfS calculation using Retail Price Index excluding mortgage payments inflation metric.

- UCAS data, cited in OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024. See UCAS, ‘UCAS undergraduate end of cycle data resources 2023’ (web page).

- Gov.UK, ‘Monthly monitoring of entry clearance visa applications’, April 2024.

- Much of the information for this section on ‘Navigating financial challenge’ is from OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024.

- For further information on universities and colleges’ duties in the area of consumer protection, see OfS, ‘Protecting students as consumers’ (OfS Insight brief #19), June 2023.

- See National Audit Office, ‘Investigation into student finance for study at franchised higher education providers’, 2024.

- See OfS, ‘Financial sustainability and market exit cases’ (OfS 2023.18), April 2023.

- For previous reports, see OfS, ‘How we regulate financial sustainability within higher education’ (web page), last updated May 2023. For the latest report, OfS, ‘Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024’ (OfS 2024.21), May 2024.

- See OfS, ‘Student protection’ (web page), published March 2021.

- The basis and arrangements for student protection directions are set out in OfS, ‘Regulatory notice 6: Condition C4 – Student protection directions’ (OfS 2021.09), March 2021.

- OfS, ‘Financial sustainability and market exit cases’ (OfS 2023.18), April 2023.

Describe your experience of using this website