Regulatory advice 24: Guidance related to freedom of speech

Last updated: 11 November 2025

Section 2: Framework for assessment

In this section:

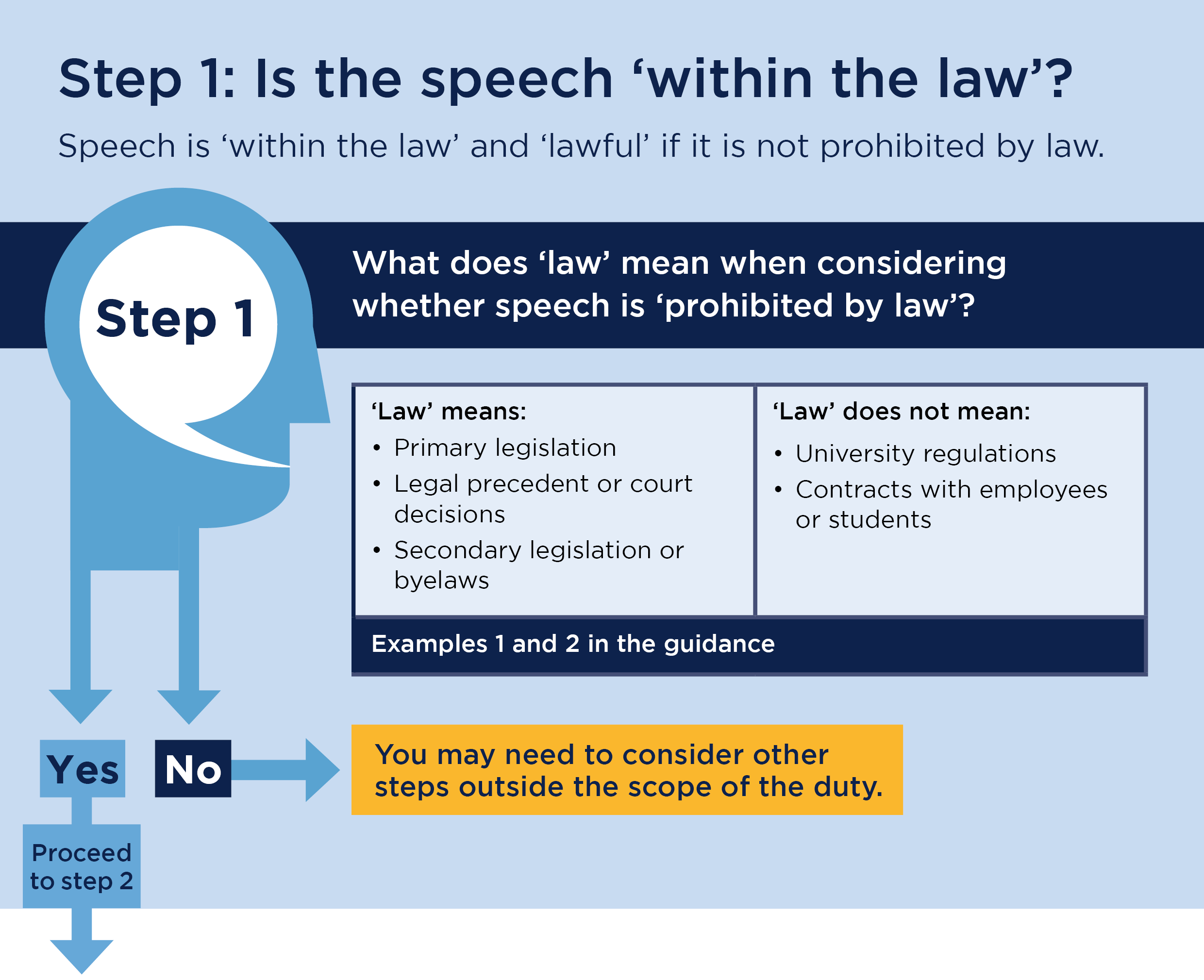

- Step 1: Is the speech ‘within the law’?

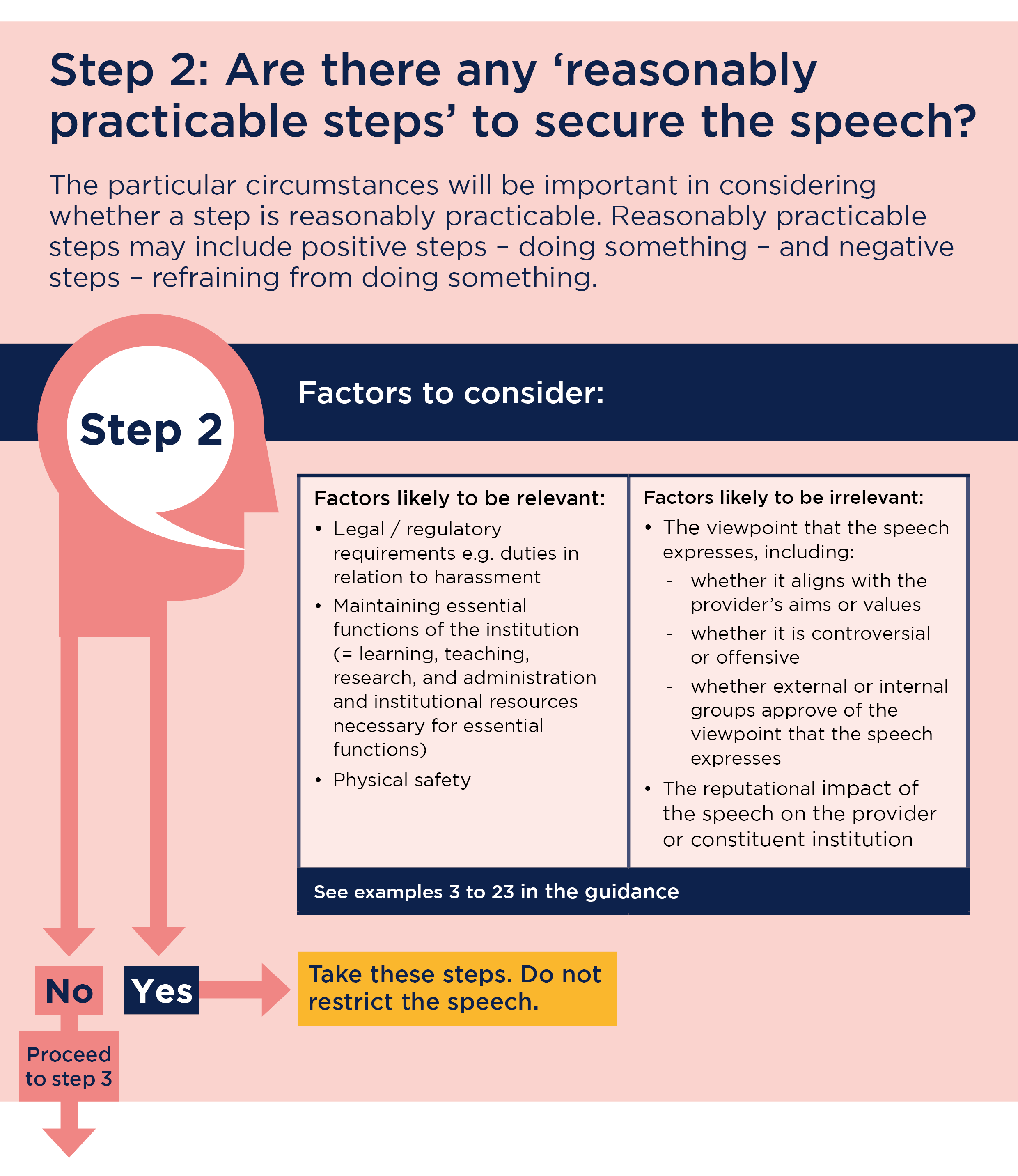

- Step 2: Are there any ‘reasonably practicable steps’ to secure the speech?

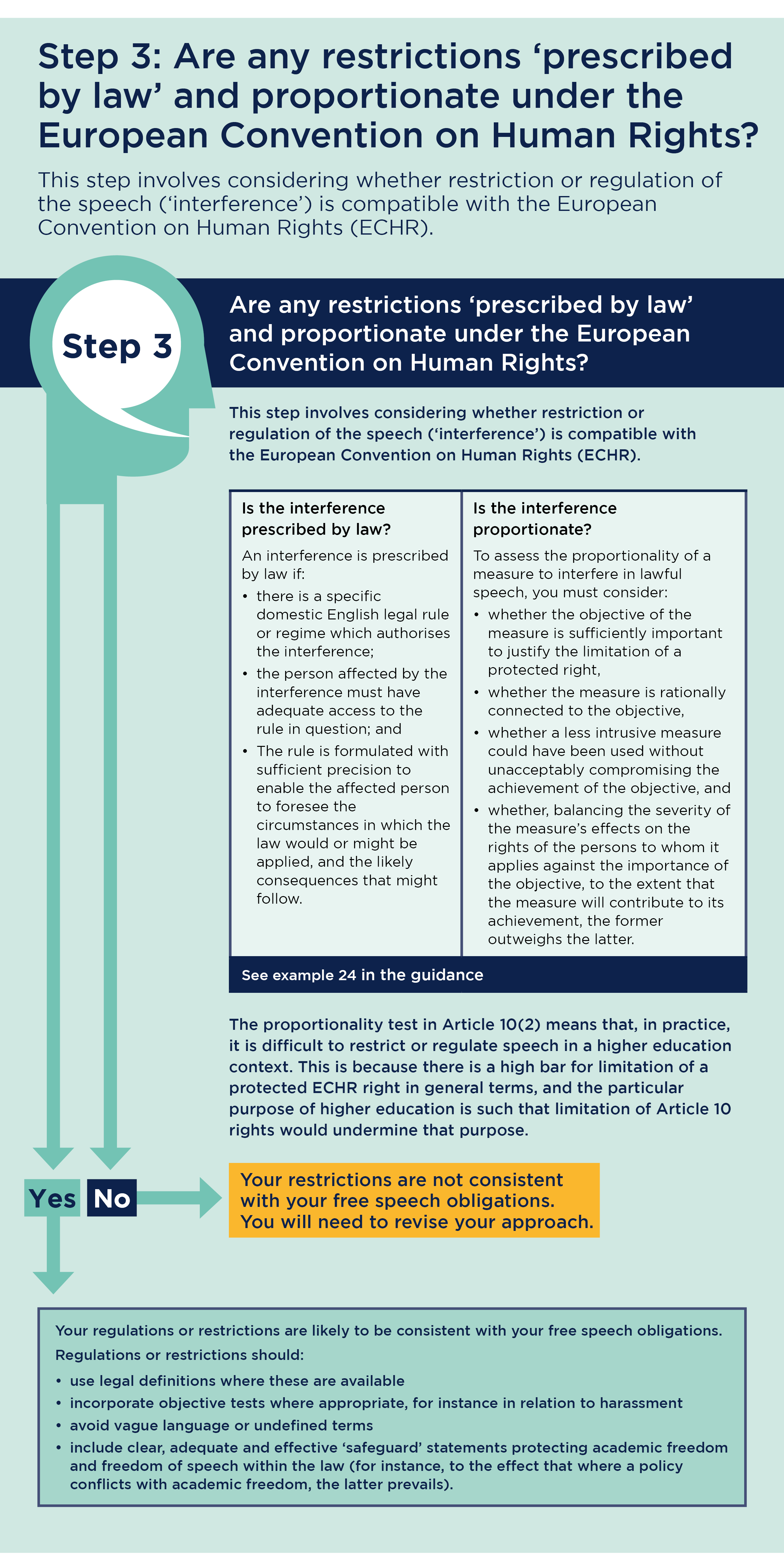

- Step 3: Are any restrictions ‘prescribed by law’ and proportionate under the European Convention on Human Rights?

- This section sets out a three-step framework that may be helpful for assessing compliance with the ‘secure’ duty. These steps apply to any measure or decision that might affect speech or types of speech.

- Providers and constituent institutions may sometimes take, or already have in place, measures that affect freedom of speech within the law. These may include policies (for instance, room-booking policies) or decisions under those policies (for instance, a decision to take disciplinary action against a member of staff).

- A provider or constituent institution will therefore wish to ensure compliance with the ‘secure’ duty in relation to any speech or type of speech. In doing so, we would expect it to be helpful to consider the following steps:

Step 1: Is the speech ‘within the law’? If yes, go to step 2. If no, the duty to ‘secure’ speech does not apply.

Step 2: Are there any ‘reasonably practicable steps’ to secure the speech? If yes, take those steps. Do not restrict the speech. If no, go to step 3.

Step 3: Are any restrictions ‘prescribed by law’ and proportionate under the European Convention on Human Rights?

Step 1: Is the speech ‘within the law’?

- The first step assesses whether the measure restricts or regulates speech that is ‘within the law’.

- This might be, for instance, because certain types of lawful speech, or potential speech, fall within the scope of a policy (for instance, a policy regulating student conduct). It might be, for instance, because a decision affects a particular speech (for instance, a decision to penalise a member of staff for writing a particular article). The first step is therefore to assess whether the speech (or type of speech) affected is lawful.

- All speech is lawful, i.e. ‘within the law’, unless restricted by law. Any restriction of what is ‘within the law’ must be set out in law made by, or authorised by, the state, or made by the courts e.g. legislation or legal precedent/court decisions. This includes (for instance) common law on confidentiality and privacy. It does not include rules made by a provider or constituent institution through contracts, its own regulations etc. (although see step 3 below on proportionate interference).

- The ‘secure’ duty does not cease to apply where a provider or constituent institution sets standards for how employees talk to one another and/or to students. Nor does it cease to apply in relation to any non-legally binding recommendations of any charter, report or review in so far as these may restrict or regulate lawful speech. Providers and constituent institutions should not set such standards or implement such requirements as are incompatible with the ‘secure’ duty.

- Freedom of speech within the law is protected. Speech that breaches either criminal or civil law is not protected. There is no need to point to a specific legal basis for speech. Instead, the starting point is that speech is permitted unless restricted by law, made by, or authorised by, the state, or made by the courts.

- Free speech includes lawful speech that may be offensive or hurtful to some. Speech that amounts to unlawful harassment or unlawful incitement to hatred or violence (for instance) does not constitute free speech within the law and is not protected: see (for instance) examples 1, 4 and 9 below.

- Many providers will be familiar with the need to assess whether actual or potential speech is within the law. The duty on universities, to take reasonably practicable steps to secure ‘freedom of speech within the law’, has existed since section 43 of the Education (no. 2) Act 1986 came into force.6 Moreover, the new free speech duties do not change what speech is lawful: speech that was not ‘within the law’ before the Act came into force does not become lawful by virtue of any provision of the Act (or vice versa).

- The following examples are not intended to form an exhaustive list of all the relevant laws. Instead they illustrate a range of legal provisions that make speech unlawful. Relevant statutes include those that create criminal offences but also those that create civil legal obligations, such as the Equality Act 2010 (see step 2 below).

Public Order Act 1986

- It is an offence under Section 4 of the Public Order Act 1986 if a person—

- uses towards another person threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or

- distributes or displays to another person any writing, sign or other visible representation which is threatening, abusive or insulting,

—with intent to cause that person to believe that immediate unlawful violence will be used against him or another by any person, or to provoke the immediate use of unlawful violence by that person or another, or whereby that person is likely to believe that such violence will be used or it is likely that such violence will be provoked.

- No offence is committed where the words or behaviour are used, or the writing, sign or other visible representation is distributed or displayed, by a person inside a dwelling and the other person is also inside that or another dwelling.

- It is an offence under Section 4A of the Public Order Act 1986 if, with intent to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress, a person—

- uses threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour, or

- displays any writing, sign or other visible representation which is threatening, abusive or insulting,

thereby causing that or another person harassment, alarm or distress.

- Such speech is not an offence where the words or behaviour are used, or the writing, sign or other visible representation is displayed, by a person inside a dwelling and the person who is harassed, alarmed or distressed is also inside that or another dwelling.

- It is a defence for the accused to prove:

- that he was inside a dwelling and had no reason to believe that the words or behaviour used, or the writing, sign or other visible representation displayed, would be heard or seen by a person outside that or any other dwelling, or

- that his conduct was reasonable.

- It is important to remember that proving intent is not enough. There must also be evidence of somebody (which need not be the person targeted) suffering actual harassment, alarm or distress as a result.

- It is an offence under Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986 if a person—

- uses threatening or abusive words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour, or

- displays any writing, sign or other visible representation which is threatening or abusive,

within the hearing or sight of a person likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress as a result.

- Speech that is merely ‘insulting’ does not amount to an offence under Section 5.

- It is a defence for the accused to prove:

- that the speaker had no reason to believe that there was any person within hearing or sight who was likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress, or

- that they were inside a dwelling and had no reason to believe that the words or behaviour used, or the writing, sign or other visible representation displayed, would be heard or seen by a person outside that or any other dwelling, or

- that their conduct was reasonable.

- For an offence to have been committed, there must be a person within the sight or hearing of the suspect who is likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress by the conduct in question.

- The following types of conduct are (non-exhaustive) examples, which could amount to disorderly behaviour under Section 5:

- causing a disturbance in a residential area or common part of a block of flats

- persistently shouting abuse or obscenities at passers-by

- pestering people waiting to catch public transport or otherwise waiting in a queue

- rowdy behaviour in a street late at night which might alarm residents or passers-by

- causing a disturbance in a shopping precinct or other area to which the public have access or might otherwise gather.7

- An offence under section 4, 4A or 5 may be committed in a public or a private place, but no offence is committed under these sections where the words or behaviour are used, or the writing, sign or other visible representation is displayed, by a person inside a dwelling and the other person is also inside that or another dwelling.

- Speech that is unlawful under the Public Order Act 1986 is not ‘within the law’ and the Act imposes no obligation to secure it.

Harassment (Protection from Harassment Act 1997)

- Harassment in the Protection from Harassment Act is different from harassment as defined in the Equality Act 2010. We discuss the Equality Act 2010 under step 2 below.

- The concept of harassment in this Act is linked to a course of conduct which amounts to it.8 The course of conduct must comprise two or more occasions.9 Harassment includes alarming a person or causing them distress.10 The fewer the occasions and the wider they are spread, the less likely it is reasonable to find that a course of conduct amounts to harassment.11 Conduct must be oppressive and unacceptable rather than just unattractive or unreasonable and must be of sufficient seriousness to also amount to a criminal offence.12

- Section 1 of the Protection from Harassment Act states that the course of conduct is prohibited if the person whose course of conduct is in question knows or ought to know that it amounts to harassment of another; and that ‘the person whose course of conduct is in question ought to know that it amounts to or involves harassment of another if a reasonable person in possession of the same information would think the course of conduct amounted to harassment of the other.’ This introduces an element of objectivity into the test.

- Speech that amounts to unlawful harassment under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 is not ‘within the law’ and the Act imposes no obligation to secure it.

Example 1: harassment through social media

Students at provider A participate in a seminar discussion concerning governing divided societies. During the discussion, student B lawfully expresses a controversial position relating to minority groups.

Following the seminar, student C publishes repeated comments on social media attacking student B, tagging them in the posts and encouraging other people to post responses to student B to tell them what they think of their views. Student C’s speech is so extreme, oppressive and distressing that their course of conduct may amount to harassment as defined in the Protection from Harassment Act 1997.

Provider A learns of the activity. It carries out an investigation of student C under its social media policy, which forbids unlawful online harassment. In doing so, it is unlikely that provider A has breached its ‘secure’ duty.

Terrorism Act 2000

- The Terrorism Act 2000 prohibits (among other things13) speech that:

- invites support for a proscribed organisation, and the support is not, or is not restricted to, the provision of money or other property; or

- expresses an opinion or belief that is supportive of a proscribed organisation, and in doing so is reckless as to whether a person to whom the expression is directed will be encouraged to support a proscribed organisation.

- It is also unlawful to address a meeting if the purpose of the address is to encourage support for a proscribed organisation or to further its activities.14

- A person also commits an offence if they arrange, manage or assist in arranging or managing a meeting which they know is:

- to support a proscribed organisation,

- to further the activities of a proscribed organisation, or

- to be addressed by a person who belongs or professes to belong to a proscribed organisation.

- Speech that amounts to an offence under the Terrorism Act 2000 is not ‘within the law’ and the Act imposes no obligation to secure it.

Example 2: speaker from a proscribed group

Members of provider A make a request to invite speaker B to talk at an online event about the cause of nationalist struggle in country C. Provider A carries out checks on the speaker and learns that speaker B has made repeated statements professing to be a member of proscribed organisation D in another jurisdiction. Provider A rejects the request citing the prohibition on inviting proscribed groups under section 12(2c) of the Terrorism Act 2000.

In doing this it is unlikely that provider A has breached its ‘secure’ duty. This is because it is unlikely that the measure is affecting lawful speech.

Other legislation

- Other legislation may also be relevant to whether speech is ‘within the law’. This includes:

Step 2: Are there any ‘reasonably practicable steps’ to secure the speech?

- The second step applies if lawful speech is affected. This step assesses whether there are ‘reasonably practicable’ steps to secure such speech. In this section we set out and illustrate factors that are likely, and factors that are unlikely, to affect what is ‘reasonably practicable’.

- Providers and their constituent institutions must take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech within the law. This means that if such a step is reasonably practicable for it to take, a provider or constituent institution must take it.

- The requirement to take ‘reasonably practicable steps’ includes a positive duty to take steps. This may include, for instance, amending policies and codes of conduct that may restrict or regulate speech.

- It also includes a negative duty to refrain from taking certain steps which would have the effect of restricting freedom of speech within the law. For instance, if a measure affects lawful speech, it may be a reasonably practicable step not to take that measure at all. This may include, for instance, not having in place a policy that restricts the range of ideas that may be expressed, not firing a member of academic staff for lawfully expressing a particular viewpoint or not cancelling a visiting speaker event because the speaker’s views are unpopular.

- In many circumstances the negative duty is likely to have greater positive impact on freedom of speech than the positive duty. It may also be less onerous than the positive duty.

- If a step (positive or negative) is reasonably practicable, then a provider or constituent institution must take it. For instance, if a controversial speaker has been invited to deliver a lecture (and has accepted), then it is likely to be reasonably practicable for the provider or constituent institution to permit (rather than to prohibit) the lecture. If so, then it must permit it so long as the speech is lawful.

- Some factors are relevant to whether a step is reasonably practicable for a provider or constituent institution to take. The following is clearly relevant: the impact taking, or not taking, the step will have on freedom of speech. Other relevant factors will be fact-specific but will likely include:

- Legal and regulatory requirements.

- Would taking or not taking the step affect the essential functions of higher education, i.e.:

- learning

- teaching

- research

- the administrative functions and the provider’s or constituent institution’s resources necessary for the above?

- Would taking or not taking the step give rise to concerns about anyone’s physical safety?

- However, relevant considerations will likely not include:

- The viewpoint that any affected speech expresses, including but not limited to:

- whether it aligns with the provider’s or constituent institution’s aims or values

- whether it is controversial or offensive

- whether external or internal groups (for example alumni, donors, lobbyists, domestic or foreign governments, staff or students) approve of the viewpoint that the speech expresses.

- The reputational impact of any affected speech on the provider or constituent institution (for more on reputation, see paragraphs 66 and 67 below).

- The viewpoint that any affected speech expresses, including but not limited to:

- The following examples are intended to illustrate these factors. In any actual case, whether a step is reasonably practicable will depend on the specific facts.

Relevant factors: legal and regulatory obligations

- If a provider or constituent institution is required by law not to do something (e.g. not to permit certain types of speech in certain circumstances), then doing it (e.g. permitting the speech) would be unlawful and therefore not reasonably practicable. Similarly, if a step that secures freedom of speech is required by law, then it would be reasonably practicable.

- For instance, it would generally not be reasonably practicable for a provider, such as a further education college, to breach the requirements of statutory guidance on safeguarding that apply to it in relation to students under the age of 18.20

- In other cases, there may be no direct conflict between the duty to secure free speech and other legal or regulatory obligations but there may be a balance to be struck. For instance, in the case of charities, charity law and the Act could both be relevant factors in trustees’ decision-making. Steps that a charity will need to take to comply with the ‘secure’ duty will depend on the specific facts and what is reasonably practicable in the circumstances. However, particular regard will need to be given to the importance of freedom of speech.

- This might happen, for instance, when charity trustees need to balance the duty to avoid exposing the charity’s reputation to undue risk against the duty to take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech. Here particular regard would need to be given to academic freedom and freedom of speech. It is very unlikely that the reputational interests of a provider or constituent institution would outweigh the importance of academic freedom for its academic staff or freedom of speech for its staff, students, members or visiting speakers.

Equality Act 2010

- An important example is equality law. Providers and constituent institutions must comply with relevant provisions of the Equality Act 2010.

Protected characteristics

- The relevant provisions relate to a set of ‘protected characteristics’. These are: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

- A protected characteristic that is often relevant in this context is religion or philosophical belief. ‘Philosophical belief’ means beliefs that are:

- genuinely held;

- a belief and not an opinion or viewpoint based on the present state of information available;

- a belief as to a weighty and substantial aspect of human life and behaviour;

- a belief that attains a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; and

- worthy of respect in a democratic society, not incompatible with human dignity and not in conflict with the fundamental rights of others.21

- The courts have found the following beliefs, among others, to be protected under the Equality Act 2010: belief in climate change,22 ethical veganism,23 gender-critical belief,24 and belief in Scottish independence.25

Discrimination

- The Equality Act 2010 prohibits unlawful discrimination. Broadly speaking, there are two types of discrimination: direct discrimination and indirect discrimination.

- In general, direct discrimination may occur where someone is treated less favourably than others, because of a protected characteristic. Direct discrimination is unlawful except in certain situations. These include exceptions for ‘occupational requirements’ in an employment context that could apply to protected characteristics, including age, sex, religion or belief.26

Example 3: Direct discrimination

Professor A at University B attempts to run a seminar series and a conference to explore issues of sex and gender. Professor A holds gender-critical beliefs: the belief that biological sex is real, important, immutable and not to be conflated with gender identity. Gender-critical beliefs are protected beliefs for the purposes of the Equality Act 2010.

Following protests about ‘transphobia’ from staff and students, the university requires her to cancel the seminar and the conference. Because of her gender-critical beliefs, the head of Professor A’s department instructs her not to speak to the department about her research, about a cancellation of her invitation to another university, or about the accusation that she is a ‘transphobe’.

In acting in this way, University B may have directly discriminated against Professor A. It is also likely to have breached its ‘secure’ duty.

- Indirect discrimination happens when there is a policy that applies in the same way for everybody but disadvantages a group of people who share a protected characteristic, and an individual is disadvantaged as part of this group. If this happens, the person or organisation applying the policy must show that it has an objective justification.27

- Indirect discrimination against students may occur when a provider applies an apparently neutral provision, criterion or practice which puts or would put students sharing a protected characteristic at a particular disadvantage.

- For indirect discrimination against students to take place, all of the following four requirements must be met:

- the education provider applies (or would apply) the provision, criterion or practice equally to everyone within the relevant group, including a particular student, and

- the provision, criterion or practice puts, or would put, students who share the student’s protected characteristic at a particular disadvantage when compared with students who do not have that characteristic, and

- the provision, criterion or practice puts, or would put, the student at that disadvantage, and

- the education provider cannot show that the provision, criterion or practice is justified as a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.28

- The mere expression of views on (for instance) theological grounds, that some consider discriminatory, does not by itself imply that the person expressing such views will discriminate on those grounds.29 This consideration is relevant when considering whether it would be reasonably practicable to employ or continue to employ (for instance) a member of teaching staff who has expressed such views.

Harassment

- The Equality Act 2010 also places duties on providers, as employers and providers of higher education, and their staff in relation to harassment.

- Harassment (as defined by section 26 of the Equality Act 2010) includes unwanted conduct that has the purpose or effect of violating a person’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for that person related to one or more of the person’s relevant protected characteristics. (Marriage and civil partnership and pregnancy and maternity are not relevant protected characteristics for these purposes.)30

- In deciding whether conduct has the effect referred to, it is necessary to consider:

- the perception of the person who is at the receiving end of the conduct;

- the other circumstances of the case; and

- whether it is reasonable for the conduct to have that effect.

- The last point (80c) is important because it introduces an element of objectivity into the test. The perception of the person who is at the receiving end of the conduct is not the only relevant consideration in determining whether the conduct amounts to unlawful harassment. The context within which the alleged harassment has taken place will also be relevant, as will any other legal rights or duties that apply in that context. For public authorities, it may also be relevant to consider whether, in cases of alleged harassment, the alleged perpetrator was exercising any of their other Convention rights (e.g. freedom of thought, conscience and religion).

- It would not be a reasonably practicable step for providers or constituent institutions to take steps to secure speech, for instance by an employee, that would amount to unlawful discrimination or harassment.

Example 4: harassment in teaching

Tutor A at University B makes aggressive and objectively offensive remarks about gay people in class. The comments appear to be directed to student C, who is gay and who finds this behaviour offensive, hostile and intimidating. Student C complains that Tutor A has harassed them. University B investigates and as a result disciplines Tutor A for his unlawful harassing conduct.

Depending on the facts of the case, the actions of Tutor A could be likely to amount to harassment under the Equality Act. Although the particular circumstances will be relevant, it is unlikely that University B is in breach of its ‘secure’ duty.

- Context is always relevant in determining whether speech is unlawful harassment. Universities and colleges have freedom to expose students to a range of thoughts and ideas, however controversial. Even if the content of the curriculum offends students with certain protected characteristics, this will not by itself make that speech unlawful.31

- In connection with harassment, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) 2019 statement on harassment in academic settings is relevant:

‘The harassment provisions [of the Equality Act 2010] cannot be used to undermine academic freedom. Students’ learning experience may include exposure to course material, discussions or speaker’s views that they find offensive or unacceptable, and this is unlikely to be considered harassment under the Equality Act.’32

See also the OfS’s condition E6.11(j) relating to harassment and sexual misconduct, set out below under: ‘Condition E6: Harassment and sexual misconduct’.

- The objective tests related to harassment under the Equality Act 2010 and the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 (see paragraphs 46-49 above), are of particular importance in a higher education context where a provider may face pressure from students or staff, or pressure from external groups, to curtail speech that is lawful but which is perceived as offensive towards a particular person or group of people. The Equality Act does not require providers or constituent institutions to protect students or others from ideas that they might find offensive.

Victimisation

- Individuals (irrespective of whether they have a protected characteristic) are also protected from victimisation under the Equality Act. Victimisation happens when an individual experiences a detriment linked to a protected act. The individual does not need to have a protected characteristic to be protected from victimisation. Providers and their constituent institutions are covered by this provision as education providers and employers. Victimisation can take place where an employer or education provider (rightly or wrongly) believes that an individual has done or intends to do a protected act.

- A protected act is any of the following:

-

- bringing proceedings under the Equality Act

- giving evidence or information in connection with proceedings brought under the Act

- doing anything which is related to the provisions of the Act

- making an allegation (whether or not express) that another person has done something in breach of the Act.

- A detriment in the context of victimisation is not defined in the Equality Act. A detriment can take many forms and can include threats. An individual is protected from victimisation even if they give evidence, provide information or make an allegation that turns out to be factually wrong if made in good faith. Bad faith (e.g. vexatious) claims are not protected.

- Protecting individuals from victimisation can also secure their freedom of speech or academic freedom. Protecting someone from victimisation can sometimes mean a negative step (i.e. choosing not to victimise) in tandem with positive steps (i.e. choosing to do something to protect people from discrimination or harassment).

Example 5: Employment victimisation

Academic A witnesses what they consider to be sexual harassment by manager B against employee C. Employee C brings a complaint against B and A agrees to be a witness in the complaint.

Manager D approaches A and explains that if they continue to support employee C in their claim A’s request for research leave is unlikely to be approved.

Depending on the facts of the case, the actions of D may victimise A as the threat to withdraw research leave may be a detriment to their employment as a result of a protected act. The detriment is likely to censor the speech of A and interfere with their academic freedom (for instance, by preventing them from pursuing research).

Reasonably practicable steps in this instance will likely include enabling A’s full participation as a witness in the complaint and considering the request for research leave on its merits.

Public sector equality duty

- The protected characteristics underpin an overarching equality duty with which public organisations must comply. This is called the public sector equality duty (PSED). It is set out in the Equality Act 2010. Universities and colleges that are public organisations for these purposes must comply with the PSED.

- The duty states that a public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to:

- eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under the Equality Act 2010

- advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it

- foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it.

- The relevant protected characteristics for these purposes are: age, disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

- The PSED is a duty to ‘have due regard’ to the need to achieve the aims set out above. Providers, and if relevant constituent institutions, should be clear about the equality implications of their decisions, policies and practices. They must recognise the desirability of achieving the aims set out above. But they must do so in the context of the importance of free speech and academic freedom, particularly in higher education. The PSED does not, therefore, impose any general legal requirement on higher education providers or constituent institutions to restrict or regulate speech.

Example 6: religious and political expression

A Jewish student puts up a mezuzah on their university accommodation doorpost. Following complaints from students alleging the symbol is politically provocative, the university requires the student to remove it to ‘maintain harmony’, and in light of the need as stated in the Equality Act ‘to foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it’. The university does not assess whether the restriction was necessary or proportionate, nor does it consider that the student’s freedom of speech includes a right to religious expression.

By prioritising objections from other students over lawful expression, the university is likely to have failed to take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech within the law and therefore to have breached its ‘secure’ duty.

More generally, providers and constituent institutions should take appropriate steps to address any chilling effect. For instance, frequent, vociferous and intrusive anti-Israel protests across campus, including outside lecture blocks and accommodation, may have a chilling effect on pro-Israeli speech or Jewish religious expression. Students may self-censor support for Israel, and Jewish students might be chilled from expressing their religious beliefs on campus. Regulation of the time, place and manner of such protests may be a reasonably practicable step to take to secure the speech of students.

- The PSED includes duties to have due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity and to foster good relations between those who share the protected characteristic of religion or philosophical belief, and those who do not share it. Depending on the circumstances, steps that encourage an environment of tolerance and open debate, with regard to the subject matter of protected beliefs, may be relevant to meeting both the free speech duties and the PSED.

Example 7: constructive dialogue

In light of recent and ongoing global conflicts, University A organises and promotes a series of topical events at which speakers and students from different sides are encouraged to take part in open and tolerant dialogue. These sessions are moderated by expert facilitators who offer models for peaceful and constructive communication.

By organising and promoting these events, University A may have advanced the aims of its PSED. It is very unlikely that in doing so A is in breach of its ‘secure’ duty.

- However, we recognise that some activities may be motivated by an intention to advance the aims of the PSED but may be in tension with, or possibly lead to breach of, the ‘secure’ duty. Several of the examples in this guidance cover cases where activities that may be intended to advance these aims are likely to be in breach of the ‘secure’ duty (including examples 15, 18, 20, 32, 35 and 39); but also cases where it is likely that they are not (including examples 4, 7, 9, 33, 47 and 54).

Equality policies

When framing their own equality policies, providers and constituent institutions may find it helpful to take the following steps, which taken together are likely to reduce risks of non-compliance with the ‘secure’ duty (see also ‘Codes of conduct’ in section 3):

- use legal definitions where these are available

- incorporate objective tests where appropriate, for instance in relation to harassment

- avoid vague language or undefined terms

- include clear, adequate and effective ‘safeguard’ statements protecting academic freedom and freedom of speech within the law (for instance, to the effect that where a policy conflicts with academic freedom, the latter prevails).

Prevent duty

- Under the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, providers and constituent institutions must have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism (the ‘Prevent duty’).

- The Prevent duty is a duty to have ‘due regard’ to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism. It is not a duty to achieve the aim. Relevant legislation specifically states that, in complying with the Prevent duty, universities and colleges must have ‘particular regard’ to the duty to ensure freedom of speech and to the importance of academic freedom.33 They must also have ‘regard’ to statutory guidance issued under section 29 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act.

Example 8: reporting on an individual at risk of radicalisation

Student A is studying at provider B. Student A is currently being offered support by Channel, the programme designed to support individuals at risk of being drawn into terrorism or violent extremism, because student A is considered to be at risk of radicalisation. Provider B gives reports to Channel on student A’s welfare and behaviour. This is because provider B is a partner to Channel and therefore has a duty (under section 38(2) of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015) to co-operate as far as reasonably practicable and appropriate with it.

Not complying with this duty is not a reasonably practicable step. Depending on the circumstances, it may be unlikely that provider B is in breach of its ‘secure’ duty.

Condition E6: Harassment and sexual misconduct

- The OfS’s ongoing condition E6 comes into force in full on 1 August 2025. It will make sure that providers have effective policies to protect students from harassment and sexual misconduct, robust procedures to address it if it occurs, and support for students who experience it.34

- Providers and constituent institutions will wish to have robust anti-bullying and anti-harassment policies. The legal duty to take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech does not prevent them from doing so. Rather, institutions must ensure that these policies are carefully worded and implemented in a way that respects and upholds their free speech obligations. In doing so, particular regard and significant weight must be given to the importance of free speech. Wherever possible, any restrictions should be framed in terms of the time, place and manner of speech, rather than the viewpoint expressed. (See paragraph 109 below).

- We have set out, in our condition of registration and guidance on harassment and sexual misconduct, our approach to the definition of harassment.

- The condition also includes paragraph E6.8 relating to freedom of speech. It requires that any provider’s approach to harassment must be consistent with the following ‘freedom of speech’ principles:

E6.11 (j)

- irrespective of the scope and extent of any other legal requirements that may apply to the provider, the need for the provider to have particular regard to, and place significant weight on, the importance of freedom of speech within the law, academic freedom and tolerance for controversial views in an educational context or environment, including in premises and situations where educational services, events and debates take place;

- the need for the provider to apply a rebuttable presumption to the effect that students being exposed to any of the following is unlikely to amount to harassment:

- the content of higher education course materials, including but not limited to books, videos, sound recordings, and pictures;

- statements made and views expressed by a person as part of teaching, research or discussions about any subject matter which is connected with the content of a higher education course.

- The requirement in paragraph E6.8 takes precedence over any other requirement of condition E6.35

- Paragraph 58 of the OfS’s guidance on condition E6 also states:

A provider is not required to take a step that interferes with lawful speech in order to meet the requirements of the condition:

- The OfS recognises that the Equality Act 2010 does not currently give rise to legal obligations for a higher education provider to address conduct by a student that amounts to harassment.

- One of the aims of this condition is to create obligations for higher education providers in respect of dealing with harassment that goes further than the existing law, but only in so far as that does not involve doing things that could reasonably be considered to have the object or effect of restricting freedom of speech within the law or academic freedom.

- A provider will need to carefully consider its freedom of speech obligations and ensure that it has particular regard to, and places significant weight on, those obligations when creating and applying policies and procedures that are designed to help protect students from harassment by other students.

- Freedom of speech obligations should not be considered to be a barrier to creating or applying policies and procedures in respect of types of conduct that may amount to harassment unless such policies and procedures could reasonably be considered to have the object or effect of restricting freedom of speech within the law and/or academic freedom.

- The following (from paragraph 59 of the guidance) is an illustrative non-exhaustive list of examples of actions a provider or constituent institution could take that are unlikely to have a negative impact on free speech within the law:

Example 9: stirring up racial hatred

Graffiti, images or insignia that stir up racial hatred are removed promptly, with support such as access to counselling, mental health or peer support groups provided to students affected. Students are informed of the actions taken and an investigation conducted to identify the perpetrators. The provider’s disciplinary process is followed with appropriate consequences imposed at the conclusion of the investigation, in line with relevant policies.

Example 10: verbal or physical threats of violence

Verbal or physical threats of violence are investigated quickly. Support is provided to students affected and, if appropriate, interim measures are put in place to protect students while an investigation is undertaken. Action is taken to identify the perpetrators with appropriate consequences imposed once disciplinary processes have concluded.

- Other conditions of registration are also likely to be relevant to whether a step to secure speech is reasonably practicable. For instance, condition B1 (academic experience) is likely to be relevant in a range of cases. Examples 12 and 14 below are examples of cases that are likely to engage these conditions. This is because steps that undermine the essential function of teaching are unlikely to be reasonably practicable steps if they are likely to breach condition B1.

Relevant factors: essential functions

- Whether steps or speech interfere with the essential functions of higher education is likely to be relevant to whether the steps are reasonably practicable. ‘Essential functions’ means teaching, learning, research and the administrative functions and resources that those three things require.

- If taking a step to secure speech (including permitting the speech) prevents the continuation of these functions, this would make it less likely that the step is reasonably practicable. We recognise that providers and constituent institutions may have to regulate lawful expression, where this is required for their essential functions. This might mean, for instance, that it may in certain circumstances not be reasonably practicable to enable protests that prevent learning, teaching or research.

Example 11: simulated military checkpoints

Students and academics protesting against the internal policies of country A set up simulated military checkpoints and force students to go through them on campus. This causes many students to miss lectures, thus seriously disrupting the everyday learning activities at University B. University B dismantles the checkpoints.

In this scenario, permitting the checkpoints to continue is unlikely to have been a reasonably practicable step that the university could take to secure freedom of speech within the law. There were other opportunities for the protestors to express their particular viewpoint.

The protest was disrupting an essential function of the university (in this case, teaching and learning). Requiring the protestors to leave would be a restriction on the place of expression but would not be punishing, restricting or regulating speech because of its viewpoint. Depending on the circumstances, it is unlikely that B has breached its ‘secure’ duty.

Example 12: intruding into classrooms and university values

A requirement that protestors should not intrude into classrooms, or attempt to shut down debate and discussion, is suitably neutral as to the viewpoint expressed. By contrast, a requirement that protests should not express views that undermine the university’s values, may unlawfully suppress the expression of a particular range of viewpoints.

- Providers and constituent institutions have an interest in continuing ordinary functions relating to student life beyond learning, teaching, research and underlying administrative functions. These might include, for instance, celebrations following graduation ceremonies or student social events. However, any regulation of speech to protect these additional functions should be narrowly tailored to that function and should not restrict the expression of any particular viewpoint.

Example 13: encampment disrupting ordinary activities

A large lawn on University A’s campus, and a nearby building, are ordinarily used for graduation ceremonies. Shortly before the next ceremony, students protesting in favour of Palestine occupy the lawn and set up tents that would prevent the ceremony and related celebrations from taking place. Because of this potential disruption, the university considers two options:

- requiring the occupiers to vacate this particular lawn for the graduation ceremony and celebrations, without restricting peaceful and non-disruptive activity on other, unused spaces nearby

- putting in place a general requirement that there will be no pro-Palestine protests on the lawn, or on other university-owned spaces within 400 yards of the lawn, for the next 12 months.

Option 1 is less likely to breach the ‘secure’ duty than option 2. Although celebrations following the graduation ceremony may not be an essential function of the university, option 1 does not meaningfully restrict the protestors’ opportunity to express their viewpoint. It is narrowly focused on a specific time and place and does not target expressive activity because of its viewpoint.

Option 2 is more sweeping and is directed at a particular viewpoint. Adoption of option 2 is more likely to be a breach of the ‘secure’ duty.

- We expect that restrictions related to essential functions or any other relevant factors, as well as any regulations related to these wider functions would, as far as possible, focus on the time, place and manner of speech. We would expect that these measures, in intent or effect, ordinarily do not restrict legally expressible viewpoints. In other words, any regulation of the time, place and manner of speech should be viewpoint-neutral. Nor should it be framed so broadly that it may be used to punish or suppress a legally expressible viewpoint.

- While restrictions on the time, place and manner of speech are themselves neutral as to viewpoint, they may sometimes be a result of the content or viewpoint that the speech expresses (see example 47 below).

- Where reasonably practicable steps can be taken to secure the lawful exercise of speech via protests, we would expect providers and constituent institutions to take them. However, the functioning of a university or college is also likely to require restriction of speech that prevents other speech, for instance speech employing the ‘heckler’s veto’. It is therefore unlikely to be reasonably practicable for a provider or constituent institution to permit without restriction speech or protest that itself disrupts speaker events, including through the ‘heckler’s veto.’ For example, this may include speech that is delivered at such a volume and for such a length of time that it prevents any other persons from being heard or from engaging in a lesson, debate or discussion. Similarly, it is unlikely to be a reasonably practicable step to allow incessant shouting in, or outside, a lecture that prevents anyone else from speaking or being heard in the lecture theatre, thereby preventing teaching and learning.

- In addition, in certain circumstances (this will be a fact-sensitive assessment) it may be necessary and appropriate for a provider or constituent institution to regulate the time, place and manner of a protest or demonstration. For example, this may be necessary if those attending a place of worship are at risk of intimidatory harassment.

Example 14: maths lecturer expressing political views

A university lecturer in maths uses his lectures not to teach maths but to express his political views at length (but within the law). University B disciplines A because of the time and place of this speech However, it does not investigate, discipline or otherwise sanction the lecturer for expressing those views (again within the law) on social media.

In taking these steps it is unlikely that B has breached its ‘secure’ duty. The lecturer’s speech is preventing an essential function of the university, in this case teaching. Therefore it is unlikely to be a reasonably practicable step to permit the speech.

- The fact that students are offended by a teacher’s views does not by itself mean that the teacher’s employment (and lawful expression of those views) has a negative effect on the essential function of teaching.

- The fact that a member of teaching staff holds views about certain groups that may include students need not, absent additional evidence of unfair treatment, mean that the teacher’s continued employment (and their lawful expression of those views) has any negative effect on the essential function of teaching. As already explained, the mere expression of views on (for instance) theological grounds, that some consider discriminatory, does not by itself imply that the person expressing such views will discriminate on those grounds.36

Example 15: views on religion

University B employs Dr C, a lecturer in philosophy. Dr C is an outspoken atheist and has published work arguing that religious belief is irrational, contradictory and often harmful to social progress; and that it is correlated with poorer scholastic achievement. In lectures, Dr C occasionally references these views when discussing epistemology and ethics, but does not single out or disparage students for their beliefs.

A group of students who identify as religious submit a complaint, stating that Dr C’s views make them feel uncomfortable and unwelcome in class. They request that Dr C be removed from teaching duties.

The university investigates and finds that:

- Dr C’s teaching is academically rigorous and respectful of students.

- There is no evidence of discriminatory treatment or exclusion based on students’ religious beliefs.

- Dr C’s views are relevant to the subject matter and expressed in a way that encourages critical discussion.

Despite this, the university decides to remove Dr C from teaching to avoid further complaints.

In these circumstances it is likely that University B has breached its ‘secure’ duty. C’s views , and her expression of those views, are lawful and do not affect her teaching. B should not have removed Dr C from teaching.

In other circumstances, action by University B may not have breached its ‘secure’ duty. For instance, if C had discriminated against any students on the basis of their religion, then it is likely that some steps to address this would not breach B’s ‘secure’ duty. These steps may in some circumstances include removing C from teaching duties.

- Many providers operate courses that lead to professional qualifications because of their accreditation by PSRBs (Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Bodies), or other accrediting bodies. Providers of accredited courses may be required to enforce professional standards, for instance through ‘fitness to practise’ procedures.37

- We recognise that teaching, including professional training, is an essential function of registered providers and constituent institutions and that this may include accreditation arrangements.

- However, providers and constituent institutions must not implement any accreditation agreement in a way that disproportionately interferes with students’ or others’ rights to freedom of expression. Where it is not possible to avoid this, providers or constituent institutions may wish to raise the need for amendments with the accrediting body.

- The following steps are also likely to be reasonably practicable steps that providers and constituent institutions should take in relation to accreditation:

- clear statements in or alongside fitness to practise policies protecting freedom of speech and academic freedom;

- highlighting of the Code of Practice on Freedom of Speech in or alongside fitness to practise policies and procedures;

- suitable training on freedom of speech for any staff sitting on fitness to practise panels (or equivalent);

- monitoring of academic departments’ implementation of fitness to practise schemes to ensure compliance with the ‘secure’ duty and with Convention rights; and

- ensuring that students are aware of the relevant professional accreditation standards, and the implications of not meeting them, even where the provider or constituent institution does not enforce them.

- Example 24 below describes a case that is of relevance in relation to PSRBs.

Relevant factors: physical safety

- Factors that are relevant to an assessment of whether a step is reasonably practicable for a provider or constituent institution to take will be likely to include whether there is any credible evidence that it may give rise to concerns about physical safety.

Example 16: protests against fracking

The chief executive of a fracking firm has been invited to discuss energy security at University A.

Protestors against fracking have previously made multiple attempts to throw paint at this speaker and this has resulted in several arrests for assault. There has been a number of calls from students opposed to the speech to disrupt it and follow similar tactics.

The university permits a demonstration opposing fracking at the same time. However, it requires that the demonstration must take place within a specified zone away from the entrance, but still within hearing distance of the lecture hall. It also provides security and introduces ticketing for the event.

The university also communicates that attempts to disrupt the event or the speaker may lead to an investigation on compliance with the university’s code of conduct.

In taking these steps, it is unlikely that A has breached its ‘secure’ duty. Permitting protests to go ahead unrestricted is unlikely to have been a reasonably practicable step, because of the credible risk to physical safety.

Example 17: human rights activist

Speaker A is a human rights activist who speaks out against country B which is an autocratic state. Country B has a long history of attempted and actual assassinations of political dissenters. Speaker A has been invited to speak in person at University C. Credible threats have been made against the life of speaker B should they attend and give their speech.

Rather than cancel the event in the face of these threats to physical safety, C hosts the speaking event online and opens the event only to staff, students and members of the university. In taking these steps University C is very unlikely to have breached its ‘secure’ duty.

- Physical safety is more likely to be relevant in relation to a specific danger that the relevant speech directly creates. Unspecific, distant or indirect potential effects of the speech are unlikely to be relevant to whether a step is reasonably practicable.

Example 18: speaker on a regional war

Dr A proposes to invite speaker C to university B on a regional war. Speaker C is strongly on one side of the issue on which they have been invited to speak. There are many international students at University B, including many from the region affected. Because of this, University B is concerned that the event may contribute to an atmosphere of religious and political tension on campus. However, there is no evidence that the event creates any immediate and specific threat to physical safety. Nonetheless, B refuses permission for the event.

Depending on the circumstances, University B may be in breach of its ‘secure’ duty. There is no direct and specific threat to physical safety from Dr C’s lecture. Physical safety concerns are therefore less relevant to the reasonable practicability of permitting the event.

In relation to broader concerns about the atmosphere on campus, University B might have taken steps short of refusing permission to Dr A. For instance, it might have offered additional seminars that take other perspectives on the same issue. It might have created additional platforms for constructive dialogue between speakers on both sides. It might have offered support to students who were affected by issues raised in the event. In taking these other steps, University B would have been unlikely to have breached its ‘secure’ duty.

- Physical safety is relevant as it relates to events within the provider’s or constituent institution’s premises or that are otherwise in its control. Threats to physical safety in external (possibly distant) locations, by persons outside its control, are not relevant to whether a step is reasonably practicable.

Example 19: controversial US senator

A controversial US politician, Senator X, has been invited to deliver a lecture at University A (and has accepted the invitation). As the date of X’s lecture approaches, groups opposed to X’s invitation stage increasingly disruptive protests around the country, though not on the campus of University A, and not involving anyone connected with A.

Some groups threaten that if the lecture goes ahead, these protests may become violent. There is no risk of violence or unmanageable protest on the campus of A. However, University A cancels the lecture in response to the threats.

In cancelling the lecture it is likely that University A has breached its ‘secure’ duty. In discharging its ‘secure’ duty, as with section 43 of the 1986 Act, the university is ‘not enjoined or entitled to take into account threats of “public disorder” outside the confines of the university by persons not within its control. Were it otherwise, the purpose of [this section] could be defeated since the university might feel obliged to cancel a meeting in Liverpool on the threat of public violence as far away as, for example, London which it could not possibly have power to prevent.’38

Irrelevant factors

- In determining reasonable practicability, the following factors are likely to be irrelevant:

- The viewpoint that the speech expresses, including but not limited to:

- whether it aligns with the provider’s or constituent institution’s aims or values

- whether it is controversial or offensive

- whether external or internal groups (for example alumni, donors, lobbyists, domestic or foreign governments, staff or students) approve of the viewpoint that the speech expresses.

- The reputational impact of the speech on the provider or constituent institution.

- The viewpoint that the speech expresses, including but not limited to:

Example 20: public statements by a visiting lecturer

Professor X has accepted an invitation as a visiting lecturer at University A. Professor X proposes to deliver a set of lectures on religion. Following the invitation, A is made aware of (lawful) public statements by Professor X that are strongly critical of Islamic attitudes towards women’s rights. These statements themselves provoke strong reactions from some student groups and staff networks. University A rescinds the invitation on the grounds that it is ‘antithetical to the value we place on inter-faith understanding’. There is no evidence that X’s lectures could include unlawful speech.

University A has not taken the step of permitting X to deliver the lectures. This step would have secured Professor X’s speech. It is likely to be irrelevant to whether this step is reasonably practicable that X has endorsed, or may express, a viewpoint that is inconsistent with A’s values or unpopular among students and staff. University A is likely to be in breach of its ‘secure’ duty. It should now take the reasonably practicable step of renewing Professor X’s invitation.

Example 21: a student’s articles on human rights abuses

Y is a student at University B researching human rights abuses in country C. Y publishes several articles, in journals and in the press, lawfully alleging such abuses by the police of country C. The ambassador of country C complains to B and credibly threatens Y. Y requests security assistance from University B. However, in response, University B suspends Y’s studies.

B has not taken the step of allowing Y to continue her studies. It has not taken the step of providing security assistance for Y. In considering whether these steps are reasonably practicable steps to secure Y’s speech, it is irrelevant that this speech expresses a viewpoint that attracts disapproval from country C.

It is likely that University B is in breach of its ‘secure’ duty and that it must now take steps to secure Y’s speech: for instance, permitting Y to continue her studies and providing security assistance. Depending on the circumstances, there may also be other steps that University B should take, for instance a statement of public support for Y.

Example 22: professor criticising employment practice

College A imposes contractual obligations on its staff, including a social media policy requiring them not to post material that is ‘unnecessarily critical’ of the college. During an industrial dispute Professor B, an academic employed at A, strongly but lawfully criticises the college’s employment practices in a public post on social media. The college investigates Professor B and issues him with a formal warning.

College A’s policy, and its action under this policy, are likely to breach its ‘secure duty’. College A should have considered taking reasonably practicable negative steps in this situation. These include not investigating Professor B, and not issuing him with a warning. They also include not imposing this restriction on the speech rights of its academic staff.

By contrast, a social media policy that simply required staff to be clear that all views posted are their own and do not represent the college’s views, would have been unlikely by itself to have breached A’s ‘secure’ duty.

Example 23: student post raising issues about accommodation

A student representative A at University Z wishes to raise issues about student accommodation that cast the leadership and governance of Z in an unfavourable light. The representative writes a post on the students’ union website describing students’ experiences of accommodation. University Z requires the student to remove this post on the grounds that if the post is reported more widely in the media, this would threaten University Z’s recruitment plans.

University Z has not taken the step of permitting the post to remain up. In considering whether this step is a reasonably practicable step to secure A’s speech, it is unlikely to be relevant that this speech expresses a viewpoint that may affect Z’s reputational interests. It is likely that Z is in breach of its ‘secure’ duty and that it must now take this step to secure A’s lawful speech.

Step 3: Are any restrictions ‘prescribed by law’ and proportionate under the European Convention on Human Rights?

- If indeed there are no reasonably practicable steps to secure speech, any restriction or regulation must meet the conditions set down under Article 10 of the Convention. The third step is to ensure that it does. This section sets out those requirements.

- Article 10(2) of the Convention is relevant to considering whether any restriction or regulation of speech (any ‘interference’) is proportionate. The European Court of Human Rights considers that interference with the right to freedom of expression may entail a wide variety of measures that amount to a ‘formality, condition, restriction or penalty’ on speech.[39]

- An interference is ‘prescribed by law’ if:

- there is a specific domestic English legal rule or regime which authorises the interference;

- the person affected by the interference must have adequate access to the rule in question; and

- the rule is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the affected person to foresee the circumstances in which the law would or might be applied, and the likely consequences that might follow.

- ‘Law’ in the context of Article 10(2) therefore has an extended meaning.[40] In this context, it may include rules set out in contracts of employment, student contracts, regulations or codes of conduct. However, any such rules must have some basis in domestic law and must meet the conditions of accessibility and foreseeability set out in 126b-c.

- The European Court of Human Rights has held that a norm cannot be regarded as a ‘law’ unless:

‘it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his or her conduct and that he or she must be able – if need be with appropriate advice – to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail. However, it went on to state that these consequences do not need to be foreseeable with absolute certainty, as experience showed that to be unattainable’.41

- The European Court of Human Rights has stated, with regard to Articles 9, 10 and 11, that ‘the mere fact that a legal provision is capable of more than one construction does not mean that it does not meet the requirement of foreseeability.’42

- Article 10(2) also requires that any interference in speech is ‘proportionate’. To assess the proportionality of a measure to interfere in lawful speech, providers and constituent institutions must consider:

- whether the objective of the measure is sufficiently important to justify the limitation of a protected right,

- whether the measure is rationally connected to the objective,

- whether a less intrusive measure could have been used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of the objective, and

- whether, balancing the severity of the measure's effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objective, to the extent that the measure will contribute to its achievement, the former outweighs the latter.43

- The proportionality test is formulated such that there is a high bar to interfere with any qualified Convention rights, including Article 10 on freedom of expression. In practice this means it is difficult to restrict lawful speech. This is particularly so in a higher education context, where providers are subject to statutory duties to secure the rights protected under Article 10, and where the core mission of universities and colleges is the pursuit of knowledge (and the principles of free speech and academic freedom are fundamental to this purpose).

Example 24: religious expression on social media

As stated by the Court of Appeal: ‘This case concerns the expression of religious views, on a public social media platform, disapproving of homosexual acts, by a student, enrolled on a two-year MA Social Work course.’

‘Upon being notified of the postings upon social media, the university, the [student’s] course provider, embarked upon disciplinary proceedings and took the decision to remove the [student] from his course, on fitness to practise grounds. The [student] sought judicial review of this decision on the basis that (i) it was an unlawful interference with his rights under Articles 9 and 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights as given effect by the Human Rights Act 1998, and (ii) the decision was arbitrary and unfair.’

The High Court dismissed the challenge, but the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal on basis (i). It found that ‘the University told the Claimant that whilst he was entitled to hold his views about homosexuality being a sin, he was never entitled to express such views on social media or in any public forum.’ It found that ‘the implication of the University’s submission is that such religious views as these, held by Christians in professional occupations, who hold to the literal truth of the Bible, can never be expressed in circumstances where they might be traced back to the professional concerned. In practice, this would seem to mean expressed other than in the privacy of the home. And if that proposition holds true for Christians with traditional beliefs about the literal truth of the Bible, it must arise also in respect of many Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and members of other faiths with similar teachings.’

It stated: ‘In our view, such a blanket ban on the freedom of expression of those who may be called “traditional believers” cannot be proportionate.’

It also stated that ‘it seems apparent to us that the position as to the condemnation of any expression of such views as those held by the [student] must have been present in the minds of key players within the University at the time… Secondly, in our view, that underlying attitude may almost certainly have led to a too-rapid and disproportionate conclusion that removal from the course was necessary, rather than the institution of a calm, continuing process of guidance of the [student], spelling out what he could and could not properly say, and the circumstances in which he could say it.’

The Court of Appeal concluded that: ‘The swift conclusion that the Appellant was ‘unteachable’, that it was for him to construe the Regulations and Guidance, for him to understand the impact of religious language on others unfamiliar with it, and that his failure to do so meant he must be removed immediately, do not seem to us to have been shown to be the least intrusive approach which could have been taken. It appears to us that this approach was disproportionate on the part of the University.’ 44

Notes

[6] See Education (No. 2) Act 1986.

[7] See Public Order Offences incorporating the Charging Standard | The Crown Prosecution Service.

[8] For this and the next three points, see Stalking or Harassment | The Crown Prosecution Service.

[9] See Section 7(3) PHA 1997.

[10] See Section 7(2) PHA 1997.

[11] See Lau v DPP [2000] 1 FLR 799.

[12] See Majrowski v. Guy's and St Thomas's NHS Trust [2006] IRLR 695.

[13] See in particular sections 11-13 of Terrorism Act 2000.

[14] For a list of proscribed organisations, see GOV.UK, ‘Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations’.

[15] See Malicious Communications Act 1988.

[16] See Communications Act 2003.

[17] See Terrorism Act 2006.

[18] See Equality Act 2010.

[19] See Public Order Act 2023

[20] See Keeping children safe in education - GOV.UK.

[21] See Grainger plc v Nicholson [2010] 2 All E.R. 253.

[22] See Grainger plc v Nicholson [2010] 2 All E.R. 253.

[23] See Mr J Casamitjana Costa v The League Against Cruel Sports: 3331129/2018.

[24] See Maya Forstater v CGD Europe and Others: UKEAT/0105/20/JOJ.

[25] See Mr C McEleny v Ministry of Defence: 4105347/2017.

[26] See Schedule 9 of the Equality Act 2010.

[27] See Direct and indirect discrimination | EHRC. For a definition of ‘objective justification’, see Terms used in the Equality Act | EHRC.

[28] See Technical guidance on further and higher education | EHRC.

[29] See R (Ngole) v The University of Sheffield [2019] EWCA Civ 1127, 5(10).

[30] See also the other forms of harassment defined at 26(2) and 26(3) of Equality Act 2010.

[31] See the OfS’s Insight brief 16, available at ‘Freedom to question, challenge and debate’.

[32] See the Equality and Human Rights Commission, ‘Freedom of expression: a guide for higher education providers and students' unions in England and Wales’.

[33] See sections 26 and 31 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015.

[34] See Condition E6: Harassment and sexual misconduct - Office for Students.

[35] See E6.4 of Condition E6: Harassment and sexual misconduct - Office for Students.

[36] R (Ngole) v The University of Sheffield [2019] EWCA Civ 1127, 5(10).

[37] See Fitness to practise - OIAHE.

[38] Watkins LJ in R v University of Liverpool ex parte Caesar-Gordon [1991] 1 QB 124, in relation to the s. 43 duty of the 1986 Education (no. 2) Act to take ‘reasonably practicable steps’.

[39] See Wille v Lichtenstein 28396/95 at 43: see WILLE v. LIECHTENSTEIN.

[40] See Lord Sumption UKSC/2016/0195 at 16: In the matter of an application by Lorraine Gallagher for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland).

[41] See Guide on Article 10 - Freedom of expression at 63; Perinçek v. Switzerland [GC], § 131.

[42] See Guide on Article 10 - Freedom of expression at 67; also Perinçek v. Switzerland [GC], § 135; Vogt v. Germany, § 48.

[43] Lord Reed in Bank Mellat vs HMT (no. 2) UKSC/2011/0040 at 74: Bank Mellat (Appellant) v Her Majesty's Treasury (Respondent).

[44] See Ngole vs University of Sheffield, [2019] EWCA Civ 1127, at 1, 3, 124, 127, 129 and 136-7. See: Ngole -v- Sheffield University judgment.

Describe your experience of using this website