English higher education 2019: The Office for Students annual review

Regulating in the interests of students

The OfS regulates higher education in England in the interest of students. As part of that regulatory role, universities, colleges and other higher education providers with students in receipt of student loans or who require visas to study in the UK must register with us. This chapter considers recent changes in the regulatory landscape leading to the establishment of the OfS, the principles and objectives underpinning the OfS’s regulatory approach, and issues emerging from the registration process.

The changed regulatory landscape

Over the last 30 years, English higher education has seen a dramatic increase in the numbers of both students and providers. In 1990, approximately 20 per cent of English people went into higher education by the age of 30;24 current projections put this figure at slightly more than 50 per cent.25 The number of non‑EU international students entering the UK increased from 42,000 in 1992 to a high of 246,000 in 2011, with 218,000 in 2019.26 As of October 2019, there are 387 higher education providers on the OfS’s Register.27

Since 1998, university students in England have had to pay tuition fees. Since then, these fees have increased: for most undergraduates, course fees are now subject to a maximum of £9,250. Students can apply for government tuition fee loans (and for maintenance loans, which are dependent on parental household income), which they begin to pay back once their income reaches a certain threshold. This means that most students contribute towards the cost of their course through income-contingent student loans. Universities and colleges consequently receive a much smaller proportion of their teaching income directly from the government.

Given this shift in funding, an increasingly diverse range of providers, and growing expectations from students and the public, a new approach to regulation was required. Within this changed environment, the OfS uses a range of regulatory tools – including registration requirements, ongoing monitoring of providers, and the publication of data and information – to ensure quality and drive improvement.

The OfS’s approach to regulation

The OfS’s approach to regulation puts students at its heart. Our mission is to ensure that every student, whatever their background, has a fulfilling experience of higher education that enriches their lives and careers. This means making sure that prospective students have the information they need to find a course that is right for them, and can be confident that the provider they choose offers good-quality courses, is financially viable, and well run.

Our regulatory framework, published in February 2018, sets out the principles that underpin our approach, and the ways in which we seek to protect the student interest.28 It lays out the expectations we have for providers, and explains how we will encourage competition and continuous improvement. It sets out a number of conditions – relating to access and participation, quality and standards, student protection, financial sustainability and governance – that providers wishing to register with the OfS will need to satisfy. This means that for the first time, higher education providers of all types are being judged against the same regulatory requirements.

Our approach is principles-based. The higher education sector is complex: imposing a narrow rules-based approach would risk creating a compliance culture that would stifle diversity and discourage innovation. The framework does not, therefore, set rigid numerical performance targets, or list detailed requirements. Instead, it describes the approach the OfS will take as it makes individual judgements on the basis of data and contextual evidence.

The OfS is committed to keeping the regulatory burden to a minimum, consistent with our role and our objectives. We apply a risk-based approach to our regulatory responsibilities. This means that we focus our attention on those providers we consider to be at increased risk of breaching one or more of our regulatory conditions. In these circumstances, we may place the provider under a greater level of scrutiny. Providers that continue to comply with our conditions should see less regulation and reduced burden, not more.

The regulatory framework sets out two levels of regulation. Provider-level regulation describes the relationship between the OfS and individual universities and colleges, the purpose of which is to ensure that all registered providers meet baseline requirements across a number of conditions, including student outcomes, management and governance, financial viability and sustainability and student protection.

Above that baseline, the framework outlines how our interventions at sector level will ensure that the higher education sector is able to diversify, innovate and flourish through activities that potentially impact on all universities and colleges. This includes championing issues, sharing evidence and examples of effective and innovative practice, promoting diversity, publishing information that enables students to make the right choices for them, and the strategic use of funding to drive improvements.

OfS regulatory framework: the four primary objectives

All students, from all backgrounds, and with the ability and desire to undertake higher education:

- Are supported to access, succeed in, and progress from, higher education.

- Receive a high-quality academic experience, and their interests are protected while they study or in the event of provider, campus or course closure.

- Are able to progress into employment or further study, and their qualifications hold their value over time.

- Receive value for money.

Regulating for equality of opportunity

The framework is also underpinned by a commitment to equality of opportunity. Some groups of students, including those from low-income homes, are still far less likely to go to university or college than students from more advantaged backgrounds. If they do go, they are far more likely to drop out before completing their course, and less likely to get a good job when they leave higher education. The primary objectives that lie at the heart of our regulatory framework are designed to address these issues and needs.

It is sometimes argued that there is a tension between these objectives: for example, that if providers recruit students from disadvantaged backgrounds, then it is inevitable that higher numbers will drop out. However, access for disadvantaged students, and good outcomes, are not a zero-sum game. Research shows that if students from disadvantaged backgrounds make the right choice about what and where to study – and are given the support they need during their studies – they can end up performing just as well as, if not better than, their more privileged peers.29

Achieving these objectives is at the heart of why we regulate. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds should not be inappropriately recruited onto poor-quality courses, and they should get the support that they need. Low continuation rates or poor graduate outcomes are not acceptable just because a student comes from a disadvantaged background. This is a waste of money for student and taxpayer alike. That is why our registration process is designed to ensure that each provider meets all the requirements set out in our regulatory framework.

The OfS Register

To be registered with the OfS a provider must, among other things, deliver successful outcomes for all its students, and demonstrate financial sustainability and good governance. To charge higher fees, it must demonstrate that it is working towards eliminating access and participation gaps for disadvantaged groups of students.

Once registered, providers and their students gain a number of benefits. Students can apply for government-backed tuition fee and maintenance loans, and for Disabled Students’ Allowances. A provider can apply to the research councils for funding, to the Home Office for a licence to recruit international students, and to the OfS for the right to award degrees and call itself a university.

The OfS Register is a single, authoritative list which assures students and taxpayers that a particular university or college meets baseline requirements across a series of measures which, taken together, mean that it offers high-quality teaching, learning and support for its students. Providers are then monitored on an ongoing basis according to the level of risk they pose to students.

The regulatory process

To register with the OfS, providers must satisfy 12 initial conditions. These are framed in terms of outcomes and seek to regulate the things that matter to students. They include commitment to closing access and participation gaps, financial viability, quality, good governance and consumer protection.

Once registered, a provider must continue to satisfy a set of general ongoing conditions. We assess the likelihood that it will breach one or more of these conditions. Where we identify an increased risk, we may decide to impose specific ongoing conditions – requirements it must comply with as an aspect of its registration. We may also decide to monitor it more closely.

Where we find a breach of a specific or general ongoing condition we will consider using one or more of a range of sanctions, potentially culminating in deregistration.

The registration process 2018-19

Over the past 18 months, we have assessed over 500 applications and registered a total of 387 providers. Around 90 applications were still in progress by October 2019, many from providers that applied after 1 May 2019. Also by October 2019, we had refused registration for eight providers and told a further 13 that we are minded to refuse registration.30

The registration process was challenging, for the OfS and for providers. The timetable set for us by the government was tight, and the timing of the transition from the old to the new legislative framework set the parameters for the process. The OfS was legally established in January 2018 to allow for the publication of the regulatory framework and guidance on how to apply for registration. But we did not commence operations, and were therefore unable to begin the registration process, until April of that year.

Our internal registration timetable was planned to align with student recruitment cycles, so as to cause minimum disruption for providers and students. In setting it, however, we had assumed that applications would be of a good standard and ready to assess.

A number of providers, of all types, made strong applications with credible evidence that all of the initial conditions of registration were satisfied. The strongest applications had engaged with the new regulatory requirements and identified where further action might be necessary, with plans to address this.

However, this was not the case for the majority. Well over two-thirds were incomplete when they were submitted. In many cases, too, the quality of the information they contained was poor.

We are, rightly, not permitted to register a provider until we are able to confirm that each initial condition is satisfied. So, these incomplete and poor quality applications necessitated follow-up enquiries and requests for information. This inevitably extended the process.

Status of applications, assessments and registrations as at 23 October 2019

- Over 500 applications were received from higher education providers to join the OfS register.

- A total of 387 providers were registered.

- Eight providers were refused registration

- The majority of applications (446) and registrations (330) were for the ‘Approved (fee cap)’ category, which allows providers to charge tuition fees up to the higher limit.

- The majority of providers on the Register (373) had been regulated under the previous higher education regulatory systems. 14 providers not regulated under the previous systems have been registered.

Regulatory interventions

We have imposed some form of regulatory intervention for the vast majority of providers that we have registered. Interventions are based on our assessment of the risk of a future breach of a condition. They vary in scale and significance. They may highlight concerns, set out actions for a provider to take, or signal our intention to undertake more frequent or intensive monitoring. In a number of cases, we have imposed one or more ‘specific conditions’, the most significant form of intervention, to mitigate increased risk of a future breach of conditions.

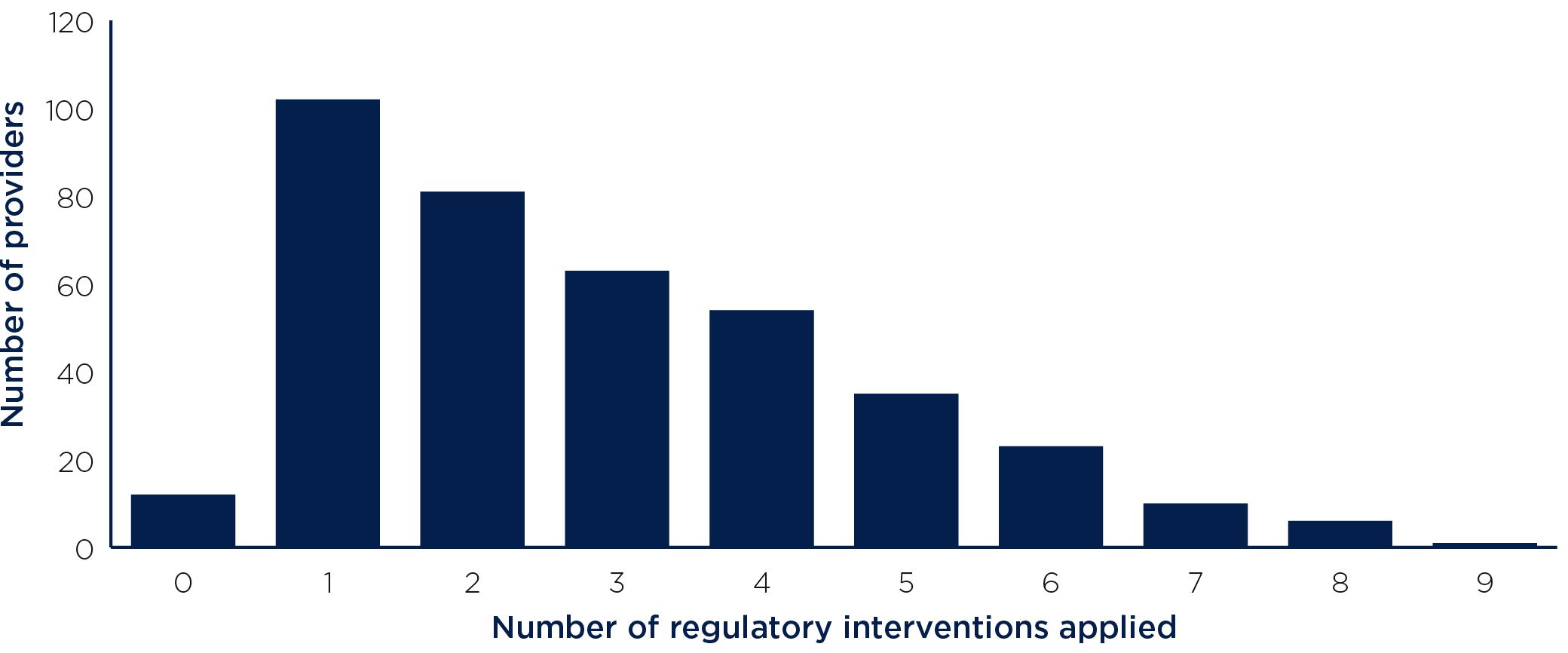

The vast majority of registered providers have had some form of regulatory intervention imposed. Some have had more than one intervention applied to them. Only 12 providers had no interventions as part of the registration decision. The total number of interventions applied as of 23 October 2019 was 1,109.31 Figure 1 provides a breakdown.

Most interventions (615) took the form of a formal communication. There were 464 requirements for enhanced monitoring, and 30 specific ongoing conditions were imposed.32

As Table 1 on page 23 shows, interventions have been imposed across all of the conditions of registration. The majority relate to the first condition, on access and participation plans. This is in large part a reflection of our level of ambition and challenge in relation to access and participation.

Fair access and participation is an important OfS objective, and there is an expectation of continuous improvement in reducing the gaps between the most and least advantaged students in access, student success and progression into further study and employment. Many providers not considered to be at increased risk for other conditions of registration were judged to be at increased risk for this condition. The greatest number of interventions (229) have been made to improve progress on access and participation by those universities and colleges that wish to charge higher tuition fees.

Regulatory interventions

The OfS has powers to impose a range of interventions, including:

- formal communication, where we inform a provider of issues that might cause us concern if left unchecked

- enhanced monitoring, where we actively monitor a provider’s progress against action plans or targets, for example financial plans or student recruitment targets

- specific conditions of registration, where we require a provider to make improvement in particular areas, for example student outcomes.

Other areas of concern

Many applications were weak in the following areas.

Sector-level data suggests there is strong performance in student outcomes, and this was reflected in the data of a large number of individual providers. However, we imposed a significant number of interventions because the outcomes delivered by some providers for their students were very weak.

Student protection plans, which set out the actions a provider will take to ensure that students can continue their studies in the event of course, campus, or provider closure, were variable in their quality. Some were excellent, and demonstrated a real engagement with the requirements, resulting in plans that had made a comprehensive assessment of risks and were clear on the protection that was available to students.

Many more, however, were very poor, and could not be approved on first or even subsequent submission. It would not have been in the interests of students to delay registration in so many cases, so we have approved a number of plans that are significantly below the standard we would expect. The providers concerned are required to resubmit improved plans following the publication of revised guidance by the OfS.

Figure 1: Number of regulatory interventions to 23 October 2019

Figure 1 is a single bar graph which shows the number of regulatory interventions the OfS has made up to 23 October 2019.

The graph shows that

- 12 providers had no regulatory interventions applied

- 102 providers had one regulatory intervention applied

- 81 providers had two regulatory interventions applied

- 63 providers had three regulatory interventions applied

- 54 providers had four regulatory interventions applied

- 35 providers had five regulatory interventions applied

- 23 providers had six regulatory interventions applied

- 10 providers had seven regulatory interventions applied

- Six providers had eight regulatory interventions applied

- One provider had nine regulatory interventions applied.

Very few providers demonstrated an understanding of value for money from their students’ perspective, and few appeared to have considered how they could present information about value for money in a way that would be accessible to their students.

We found significant weaknesses in providers’ responses to the ‘fit and proper person’ public interest governance principle. Most relied on declarations from governing body members. It was unclear whether they had conducted checks to determine whether individuals were fit and proper, and there was limited recognition of the indicators and definitions set out in the regulatory framework. Our own investigations uncovered large numbers of discrepancies between the directorships and trusteeships held by individuals declared on providers’ application forms and those listed on Companies House or the Charity Commission website.

There was a lack of convincing evidence about the adequacy and effectiveness of providers’ management and governance arrangements. A large number of providers were unable to evidence regular external input into reviews of their arrangements. There was also a reliance on what appeared to be paper-based compliance exercises against a chosen code. This did not allow the OfS to make judgements about the effectiveness of arrangements and in a number of cases we required a review of management and governance arrangements before reaching a registration decision.

Significant numbers of providers had based their financial viability and sustainability on optimistic forecasts of growth in student numbers without convincing evidence of how this growth would be achieved.33

The financial state of English higher education

Overall, higher education is in sound financial health, though with considerable variation between providers.34 However, in a period of great economic and political uncertainty, and with the unique nature of the higher education market constraining the responses of universities and colleges, it remains to be seen how well the sector will maintain this.

Universities’ and colleges’ financial commitments to the sector’s various pension schemes are having a significant impact on their financial sustainability. The 2017 triennial valuation of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) has resulted in significantly increased annual cash contributions from both employers and scheme members, which we estimate will add over £500 million a year to the annual pension bill for some universities and colleges. There is also a significant accounting adjustment due to the increased deficit in the scheme, which we will take into account when assessing the underlying financial performance of universities.

Some universities and colleges have also been impacted by requirements for increased contributions to the Teachers’ Pension Scheme, totalling an estimated £100 million a year or more. Local Government Pension Schemes are also due for a revaluation, which, if it follows the trend of other scheme valuations, could lead to further costs.

To compensate for the reduction in capital funding from the government, and given relatively cheap interest rates and long‑term loans spread over 30 to 40 years, universities and colleges have also increased their aggregate borrowing substantially over the last decade.35 Much of this money has been spent on building and improving university estates and infrastructure, such as student accommodation, teaching facilities and libraries. Private halls have been seen as a major investment opportunity, often with institutional support. It remains important that, with rents on the rise in many cities where students live, universities and colleges continue to ensure the availability of high-quality, good‑value and affordable accommodation for their students.

Table 1: Regulatory interventions across conditions of registration

| Condition | Formal communication | Enhanced monitoring | Specific condition |

|---|---|---|---|

|

A1: Access and participation plan |

144 |

77 |

8 |

|

B1: Quality |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

B2: Quality |

30 |

42 |

0 |

|

B3: Quality (student outcomes) |

50 |

77 |

20 |

|

B4: Standards |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

B5: Standards |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

C1: Guidance on consumer protection law |

15 |

6 |

0 |

|

C3: Student protection plan |

67 |

27 |

0 |

|

D: Financial viability and sustainability |

74 |

71 |

0 |

|

E1: Public interest governance |

176 |

70 |

1 |

|

E2: Management and governance |

40 |

72 |

1 |

|

F3: Provision of information |

16 |

13 |

0 |

|

Total |

615 |

464 |

30* |

Note: The number of specific conditions set out in Table 1 is higher than the number currently published on the Register. This reflects the fact that this regulatory intervention was imposed at the point of registration. The requirements of some specific conditions have subsequently been satisfied, and the specific conditions therefore removed.

Conclusion

Much of the work the OfS has done in regulation over the last year has been assessing registration applications from providers. We now know more about individual providers, and the sector as a whole, than ever before. This gives us a solid foundation for the implementation of a risk-based system of regulation in which regulatory activity is focused on those providers and those issues that represent the greatest risk to students. Through regular monitoring and intervention where necessary, our regulatory work with providers should ensure that providers continue to meet expectations.

In light of the lessons we have learnt, our focus in the coming year will be on embedding our approach to the ongoing monitoring of registered providers. To this end, we have published additional guidance setting out our processes and expectations,36 and are implementing an online system for the collection of information and data.

24 ‘The Dearing report: Higher education in the learning society’, 1997 (available at www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/dearing1997/dearing1997.html), p20.

25 DfE, ‘Participation rates in higher education: 2006 to 2018’, 2017, p1 (available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/participation-rates-in-higher-education-2006-to-2018). Rather than confirmed university entry, these figures express the likelihood that a young person will participate in higher education by the age of 30.

26 ONS, ‘How has the student population changed?’, 2016; ONS, ‘Provisional long-term international migration estimates’ (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/

datasets/migrationstatisticsquarterlyreportprovisionallongterminternationalmigrationltimestimates). Note that these figures are not directly comparable as the method used to derive them has changed since 1992, to a method still designated as ‘experimental’. Additionally, the number for 2019 is an estimate based on incomplete quarterly figures and may change in future.

27 The OfS Register, 2019 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/the-register/the-ofs-register/).

28 OfS 2018.01 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/securing-student-success-regulatory-framework-for-higher-education-in-england/).

29 Boliver et al, ‘Using contextualised admissions to widen access to higher education: A guide to the evidence base’.

30 Information on applications that have been refused can be found at OfS, ‘Refused registration decisions’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/the-register/refused-registration-decisions/). Following a decision to refuse registration, the OfS liaises with the provider regarding publication of that decision. There can therefore be a delay between the notification of the decision and publication. In some circumstances the OfS might agree that the decision should not be published.

31 OfS 2019.30, p3.

32 OfS 2019.30, p20.

33 In April 2019 the OfS wrote to providers about this issue: see OfS 2019.14.

34 OfS 2019.14.

35 OfS 2019.14, pp13-14.

36 OfS, ‘Regulatory advice 15: Monitoring and intervention’ (OfS 2019.29), October 2019 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/regulatory-advice-15-monitoring-and-intervention/).

Describe your experience of using this website