Improving opportunity and choice for mature students

The opportunity to study as a mature student is essential for equality of opportunity. It provides essential skills for future prosperity, especially as the UK recovers from the pandemic. While numbers of mature students in higher education have declined, particularly for certain types of study, there are positive signs of increasing demand. The government proposes to nurture this growth through its Lifelong Loan Entitlement, and the OfS is working for change through improved information, advice and guidance, regulation in the form of access and participation plans, and funding initiatives to encourage greater flexibility and choice.

- Date:

- 27 May 2021

Read the brief

Download the Insight brief as a PDF

Get the data

Download the Insight brief data

Read the Insight brief online

- Introduction

- Background

- Motivation

- Case study: University Centre Telford

- Part-time and full-time study

- Where mature students study

- Case study: Blackpool and the Fylde College

- Challenges for the sector

- Case study: Deakin University, Australia: A welcoming environment for cloud learners

- What the OfS is doing to drive change

- Conclusion

Introduction

The promise of higher education is that it allows individuals – at any age – a chance to learn new skills and open up new opportunities. For mature students, university or college can be a second chance to learn, an avenue to a new career, and an opportunity to earn more money.1 The decision to go into higher education is often a more challenging one for them to make, and the consequences of it greater, than for young students.2

Mature students as a group (defined as those who enter higher education at the age of 21 or over) are often overlooked. They have different motivations and needs from young students.3 Over the last 15 years, the number of them entering higher education has declined significantly, driven by a drop in those studying part-time and those pursuing a qualification below a full degree.4

In the UK, a significant proportion of adults do not participate in any form of learning, with a third or more of the respondents to the Learning and Work Institute’s annual survey reporting that they have done none since full-time education.5 Around a fifth of the adult population does not have upper secondary education; less than half have tertiary education.6 In 2018, 1.3 per cent of the UK population aged over 25 were enrolled in a bachelors’ degree or higher qualification – lower than international competitors such as Australia (3.8 per cent) and the USA (2.1 per cent).7 Many UK businesses report a lack of skilled graduate employees.8

The pandemic has seen an increase in unemployment.9 Some industries – such as hospitality, retail and tourism – have suffered more than others. Others, such as nursing, have seen increased interest as people are inspired by the work of frontline workers.10 Some parts of the country have been impacted more by lockdowns and unemployment than others.11 Remote learning, widely adopted during lockdown, could provide more flexible learning opportunities for the adult workforce.12 The pandemic and resulting economic downturn could therefore see an increased demand for higher education, as people who are made redundant want to retrain, and graduates seek higher qualifications to be more competitive in the job market.

The Office for Students (OfS) is committed to ensuring that mature students have the same opportunities as younger students. Our aim is that they should have the chance to study in higher education in a way that fits around their other commitments. We are working to expand outreach programmes such as Uni Connect to cover those beyond school age, and to increase the focus on mature students in access and participation plans.

This Insight brief comes at a critical juncture. In the Skills for Jobs white paper, the government has signalled its intention to introduce the Lifelong Loan Entitlement to make it easier to access training throughout people’s lives and prioritise the skills that employers need.13 The government has followed this up with proposals in the Skills and Post-16 Education Bill, which was announced in the 2021 Queen’s Speech. Central to the proposals is a plan to provide loans for both adult training and higher education courses beyond Level 4 on an equal footing, with greater access to modular provision to enable adults to update their skills flexibly and return to learning when it suits them.

Background

In 2018-19, there were 478,000 mature students studying at undergraduate level at English higher education providers (30.2 per cent of the total number of undergraduates). Almost all postgraduate students are mature – 480,000 or 99.2 per cent of the total in 2018-19.14 Since 2010-11, the number of UK-domiciled undergraduate mature students entering English higher education providers has declined by 19.2 per cent, a reduction of some 47,000 students – although this figure disguises a significant change in the balance between part-time and full-time study, discussed later in this brief.

Mature students often have more complex needs than younger students. They are more likely to be disabled, come from more deprived areas, or have family or caring responsibilities.15 If they are a part-time student, their primary focus might not be higher education. They may be a parent or carer, and may work full or part-time. Overall they are slightly more likely to be white, but in older age groups the percentage of black students among applicants offered places increases.16

There is a long history of mature students’ needs driving change in English higher education. This includes the expansion of adult education in the 1870s, the establishment of universities such as Birkbeck College and the Open University catering to part-time needs, the introduction of higher education courses in further education colleges, and new providers focused on professional development and flexible learning.17 To an extent, higher education is still conceived of as something mainly for young people, with an expectation that most students will want to experience the ‘residential model’ of university.18 Mature students’ experience of higher education is often different. They are less likely to live on campus, more likely to live in their own home all year round, and more likely to commute.19

Characteristic analysis of the 2020 National Student Survey shows that 70.1 per cent of respondents aged 25 and above agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘I feel part of a community of staff and students.’20 This is significantly over the benchmark we would expect, taking into account the group’s other characteristics.21 A recent report examining how to support mature students found that those surveyed were interested in whether there would be other mature students on their courses, but were less concerned about social opportunities with other students.22

It is difficult to measure educational or social disadvantage for mature students. Measures used for younger students – such as free school meals (to gauge poverty) and the Participation of Local Areas measure (POLAR) (to measure educational disadvantage) – often do not have the same meaning once students have become more independent of parental ties. As a recent review of access and participation data concluded, a ‘lack of availability of datasets for targeting outreach activities for mature and part-time learners emerges as a major gap.’23

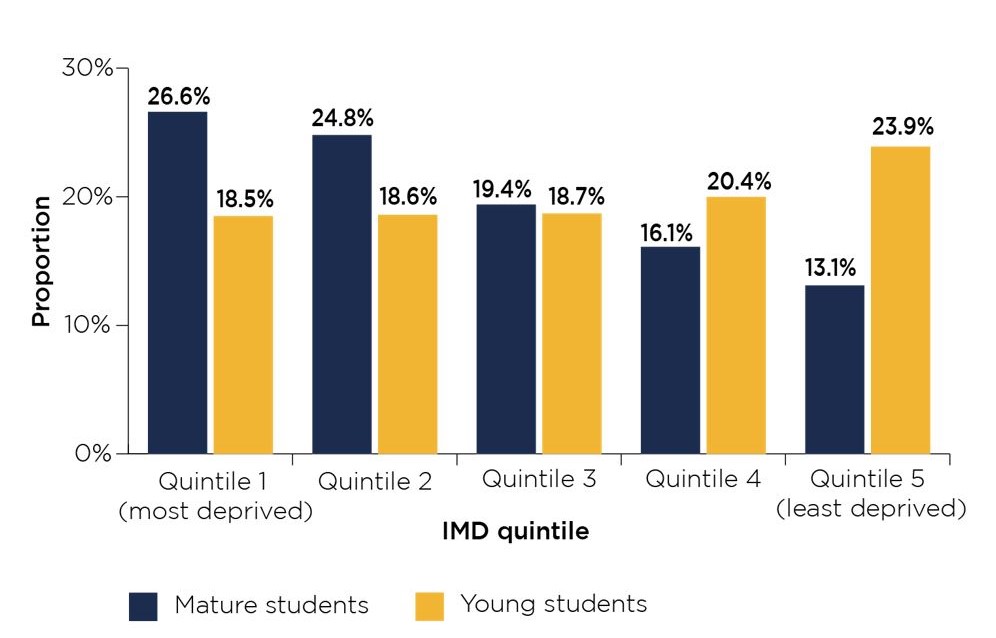

Some broader-brush area measures are available. For example, looking at the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), more than twice as many mature students (26.6 per cent) live in the most deprived areas as in the least deprived (13.1 per cent). This pattern is even more pronounced for full-time mature students. This reverses what is seen with young students, only 18.5 per cent of whom come from the most deprived areas and 23.9 per cent from the least.24 This can be a somewhat crude measure of deprivation, since in urban areas deprived streets can be close to richer ones, and a mature student’s last address before entering higher education may well differ from the area where they grew up. It nonetheless points to mature students living with more deprivation than their younger counterparts. That mature students are more likely to come from deprived areas shows the importance of higher education for opening up opportunities later in life.

Figure 1: Proportion of young and mature UK-domiciled undergraduate entrants at English higher education providers by IMD quintile in 2019-20

Source: OfS mature students datafile.25

Figure 1 is a bar chart showing the proportion of young and mature UK-domiciled undergraduate entrants at English higher education providers by Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile in 2019-20.

It shows that more than twice as many mature students live in the most deprived areas as in the least deprived. This is the reverse of what is seen with young students, only 18.5 per cent of whom come from the most deprived areas and 23.9 per cent from the least.

It shows the following proportions by quintile:

- Quintile 1 (most deprived) – 26.6 per cent of mature students and 18.5 per cent of young students.

- Quintile 2 – 24.8 per cent of mature students and 18.6 per cent of young students.

- Quintile 3 – 19.4 per cent of mature students and 18.7 per cent of young students.

- Quintile 4 – 16.1 per cent of mature students and 20.4 per cent of young students.

- Quintile 5 (least deprived) – 13.1 per cent of mature students and 23.9 per cent of young students.

Motivation

The motivations of mature students are often different from those of students who entered higher education at 18 years old. Some were not able to begin higher education as teenagers because of a lack of qualifications, or because they were not encouraged to apply. Some may have had negative experiences of education, or did not feel they would ‘fit’, or chose a competing option such as a further education qualification or entering a workplace straight from secondary school.26 Some may wish to retrain, earn more money and have wider employment choices, or to learn something new.27 These new skills can be useful to the national economy, filling gaps in sectors like IT and the NHS.

Degree apprenticeships attract a high proportion of mature students. In 2018-19, 67.9 per cent of degree apprentices were over 21 when they started their courses, compared with only 29.7 per cent on traditional higher education courses.28

Entering higher education as a teenager is not always possible, or the best option for the individual. For the most marginalised, entering higher education later can be life-changing. Some disadvantaged groups, such as care-experienced students, might benefit from higher education at this stage.29 Among those in prison, entering higher education can reduce reoffending.30 For adult refugees, higher education can be a transformational part of a new life in this country.31

Case study: University Centre Telford

University Centre Telford is the first of the University of Wolverhampton’s Regional Learning Centres and is located in the heart of Telford above the public library. It is based on a model of collaboration using a whole-community integrated approach aligned with local economic and social needs, including higher skills to drive the local economy. It aims to increase awareness of higher education for all, enable progression routes and offer relevant courses locally.

The centre plays a key role in community engagement, working to engage and nurture prospective and current learners through bespoke information, advice and guidance, tasters, lectures and participation in community and Telford-wide events. Staff work with partners to identify barriers to learning and remove them, through initiatives such as an English Cafe and public lectures. Evidence shows that this approach benefits learners, the community and the wider economy. During the pandemic, learning has been essential in addressing the wellbeing of the communities who make up Telford, and the centre has played a key role.

The centre has increased participation for employee learners through courses in management and marketing and in education, and through top-up degrees for further education students. It is focused on expanding specialist provision to match employment and skills needs in the area.

The university’s approach is based on sustained engagement with education, business, third sector and public sector partners to deliver what is needed in key locations. The centre represents a commitment to regional economic growth and development, and its success has led to other Regional Learning Centres and to major increases in investment, higher education provision and opportunities for mature learners to study locally.

Part-time and full-time study

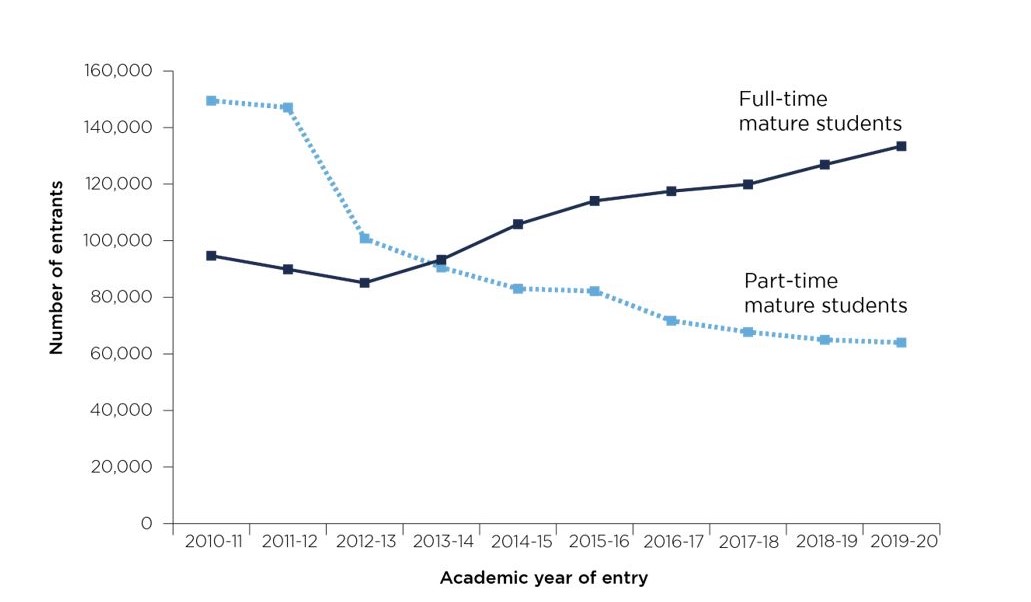

While the motivations for going to university or college may not have changed much over the last two decades, there has been a change since the turn of the century in how mature students study. In 2010-11, 149,000 part-time mature students entered higher education. By 2019-20, this number had more than halved to 64,000 – a decline of 57 per cent. In contrast, the numbers of mature students studying full-time have gone up by 41 per cent since 2010-11; these students now outnumber their counterparts studying part-time. In this way, the ‘typical’ mature student has changed markedly over the last decade: most are now studying full-time, even while the vast majority of part-time students remain mature. This shift coincided with a decline in part-time undergraduate study below a full degree, and a rise in full-time first degree study.32

Figure 2: Number of mature UK-domiciled undergraduate entrants at English higher education providers by mode of study from 2010-11 to 2019-20

Source: OfS mature students datafile33

Figure 2 is a double line graph showing the difference in the number of mature students entering English higher education by mode of study between 2010-11 and 2019-20.

It shows, over the period under examination, that the number of part-time entrants has more than halved while full-time entrants have increased year on year since 2012-13.

It shows that:

- In 2010-11, there were 94,670 full-time mature entrants and 149,480 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2011-12, there were 89,880 full-time mature entrants and 147,080 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2012-13, there were 85,100 full-time mature entrants and 100,750 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2013-14, there were 93,270 full-time mature entrants and 90,540 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2014-15, there were 105,800 full-time mature entrants and 83,040 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2015-16, there were 114,060 full-time mature entrants and 82,160 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2016-17, there were 117,480 full-time mature entrants and 71,720 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2017-18, there were 119,900 full-time mature entrants and 67,730 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2018-19, there were 126,880 full-time mature entrants and 64,970 part-time mature entrants.

- In 2019-20, there were 133,410 full-time mature entrants and 63,980 part-time mature entrants.

This shift is not new. Part-time numbers peaked in the mid-2000s and have been declining – albeit at different rates – ever since.34 There are various reasons for this decline. In 2008, the government stopped offering loans and living costs (with a few exceptions) for students studying for a qualification at a level equivalent to or lower than one they already held.35 The increase in tuition fees to up to £9,000 in 2012 also had an impact – especially the stipulation that study intensity must be over 25 per cent of full-time course to qualify for government loans.36 Since the recession of 2007 to 2009, employers appear more reluctant to fund courses for their staff.37 Led by changes to student loans, universities and colleges have increasingly focused on full-time provision to the detriment of part-time provision.38 However, many newer providers offer courses and provision (often more locally) that is attractive to mature students.

Mature students seem far more averse than young students to taking on debt to study in higher education. Survey research has shown that financial concerns, such as tuition fees and living costs, were among the top reasons those who considered entering higher education as mature or part-time students in the end decided not to.39 Tighter household budgets after a decade of pay freezes and benefit cuts are often cited as a factor in dissuading mature students from taking the leap into higher education.40 Some of this drop-off in numbers may also be a loss of people who are learning for learning’s sake, rather than primarily to increase their employability.41

Nor is it altogether clear that these ‘lost’ part-time students are learning in other ways. It seems unlikely that there is much transference from part-time to full-time study.42 The decline in the availability of part-time study options means that higher education is increasingly an impossibility for groups like those with caring responsibilities, who cannot attend full-time.43 For many, the reduction in part-time options means the loss of their chance to enter higher education at all. The lack of short courses means that people who only want or need the knowledge in a single module are less likely to turn to universities or colleges.44

Even while the potential motivations of mature students are manifold, the options open to them have become more restricted. A wide variety of part-time options also benefited other groups, such as younger students who wanted to reduce course intensity because of disability or becoming parents during their courses. Not only do these individuals miss out on the opportunity to benefit from higher education, but the university or college does not benefit from their broader variety of outlooks and lived experience.

It is not a given that the period following the pandemic will see a rise in older people entering or re-entering higher education. After the 2007 to 2009 recession, there was a much greater fall in older mature students studying part-time than in younger ones.45 To ensure that as many people as possible can benefit, in May 2021 the Queen’s speech introduced a bill which would establish the Lifelong Loan Entitlement, equivalent to four years of post-18 education.46 This is expected to allow mature students to study part-time and benefit from the equivalent funding to those studying full-time, including at a lower intensity.

Where mature students study

Regional inequalities in higher education matter more to mature students than some other groups, as they are less likely to be able to move for higher education. Younger students tend to move further and therefore often have greater choice of institutions.47 There are also higher education cold spots, especially in the rural and coastal areas of England, which could limit choice for those who cannot move far from their home region for education.48

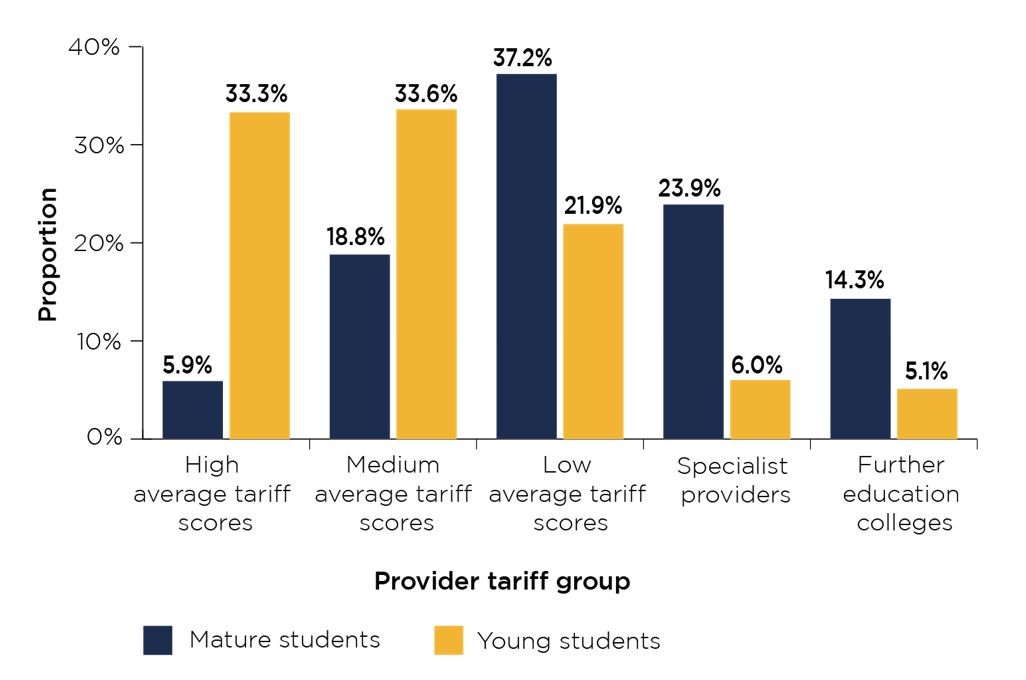

Mature students are more likely to attend specialist providers and less selective universities than younger students. In 2019-20, more than a third (37.2 per cent) of mature undergraduates entering higher education went to universities with low average tariff scores (which often reflect entry requirements), while roughly a quarter (23.9 per cent) went to specialist providers.49 By contrast, of young entrants in 2019-20, only 21.9 per cent studied at universities with low average tariff scores, while 6.0 per cent began their studies at a specialist provider.

Mature student representation at more selective universities (those with high average tariff scores) has declined from 8.8 per cent in 2010-11 to 5.9 per cent in 2019-20 – a reduction of 10,790 students in absolute terms. Meanwhile, the proportion of mature students starting higher education courses at further education colleges has nearly doubled, from 7.8 per cent in 2010-11 to 14.3 per cent in 2019-20 (from 18,980 to 25,960 entrants). This shift means that opportunities to progress from further into higher education – including through further education colleges and universities working together – are particularly important for mature students.

This change could be for a number of reasons. The more selective universities could be focusing on recruiting young students at the expense of mature students. Mature students could be choosing to study at other universities and colleges because they offer more flexible provision. They could also have little choice if they cannot move far from their home town.50

Figure 3: Proportion of UK-domiciled undergraduate entrants at English higher education providers by provider tariff group in 2019-20

Source: OfS mature students datafile.51

Figure 3 is a double bar graph that shows the difference in the type of provider mature and young students attend. It shows that young students are more likely to attend providers with high and medium average tariff scores. In contrast, mature students are more like to attend providers with low average tariff scores and specialised providers.

It shows the following proportion by provider:

- High average tariff scores – 5.9 per cent of mature students and 33.3 per cent of young students.

- Medium average tariff scores – 18.8 per cent of mature students and 33.6 per cent of young students.

- Low average tariff scores – 37.2 per cent of mature students and 21.9 per cent of young students.

- Specialist providers – 23.9 per cent of mature students and 6.0 per cent of young students.

- Further education colleges – 14.3 per cent of mature students and 5.1 per cent of young students.

Case study: Blackpool and the Fylde College

Blackpool and the Fylde College has a focus on upskilling and reskilling students to meet the needs of the economy and facilitate social inclusion. ‘Flying Start’ is the college’s principal programme supporting transition into and between levels in higher education for all students, offering essential study preparation.

Since the average age of students at the college is 28, with many having had a break in education, the Flying Start programme was developed from a need to ensure that students are prepared to enter and progress through higher education. Confidence, resilience and experience are deepened through blended delivery workshops that offer inspiration through practical advice and resources, to help manage study and familiarise students with available support.

Digital access and support are integrated into the students’ experience through a mobile-enabled virtual learning environment introduced at the beginning of their digital journey. The content responds to the predominantly mature student demographic, including focused discussions around returning to study and changing careers, and time management alongside other commitments.

To understand the effectiveness of Flying Start, the college monitors the performance of attendees throughout their student lifecycle through various measures, with clear benefits seen in the retention of students who participated in the workshops.

Flying Start complements the carefully considered provision offered by the college that the Centre for Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education’s recent research has found is attractive to the mature student lifestyle, namely flexible and condensed timetabling allowing mature learners to manage existing commitments, class sizes that are typically smaller than at a university, and the majority of students living locally.

Mature students currently have better progression into highly skilled employment or further study than young students. Of undergraduate mature students studying full-time before graduating in 2016-17, 75.7 per cent progressed into highly skilled employment or further study, a rate 3.4 percentage points higher than for young students (72.3 per cent). Rates for part-time mature students were similar to full-time (75.8 per cent), and higher than young part-time students (by between nine and 14 percentage points). It should be noted, however, that young part-time study is uncommon.52

This is, of course, influenced by the extent to which mature students may be studying while already in a highly skilled job, or choosing subject areas with better progression outcomes. Mature students are often studying with a specific job in mind, whereas young students may take more time to decide what career to enter.53

The ability to move to London gives an individual a greater choice of graduate jobs, but for those with commitments to a particular place, such migration is less practical.54 In 2019 the OfS funded 16 projects across England to improve the employment prospects for graduates who stay in their home regions. Through a range of initiatives, including curriculum interventions and internships, these projects are supporting the transition into highly skilled work.55

Projects like these will potentially open up a greater choice of graduate jobs for those who cannot move for work – a group which includes many mature students. They will allow graduates to contribute to their local area, fill skills gaps, and drive prosperity.

Challenges for the sector

While higher education can be transformative for mature students, it is not always geared towards their needs. Mature students are more likely to discontinue their studies. In 2018-19, 84.4 per cent of mature full-time students continued onto their second year, a rate eight percentage points below that for young students. Of part-time mature students, around two-thirds continued into their second year. This was 6.6 percentage points below their younger counterparts.56

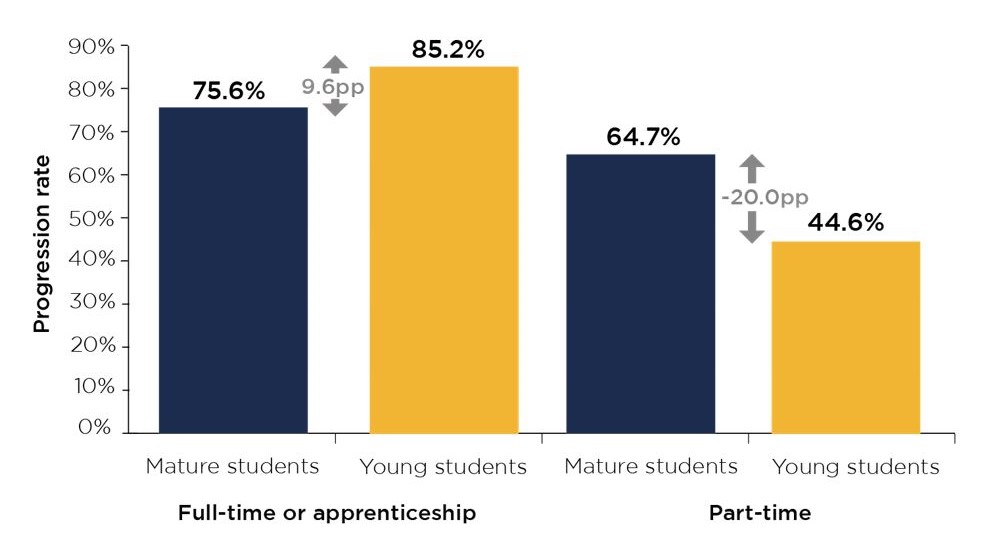

There is also a degree attainment gap between mature and young students (see Figure 4). In 2019-20, for full-time undergraduates, this gap was 9.6 percentage points.57 It has, over recent years, been narrowing. Numbers of young part-time students are small, but the data suggests that attainment is higher (by between 16 and 24 percentage points) among mature part-time students than their younger counterparts.58

Figure 4: Differences in UK-domiciled undergraduate rates of achieving a first or upper second class degree by age and mode of study in 2019-20

Source: OfS access and participation data dashboard.59 Note: ‘pp’ = ‘percentage point’.

Figure 4 is a double bar graph that shows the difference in degree attainment between mature and young students in 2019-20. It shows that, among those studying full-time, young students were more likely to achieve a first or upper second degree than mature students. For part-time students, mature students were more likely to attain a first or upper second degree than younger students.

It shows that:

- Among full-time undergraduates and apprenticeship students, 75.6 per cent of mature students achieved a first or an upper second class degree compared with 85.2 per cent of young students. The gap between these two rates is 9.6 percentage points.

- Among part-time undergraduates, 64.7 per cent of mature students achieved a first or an upper second class degree compared with 44.6 per cent of young students. The gap between these two rates is -20.0 percentage points.

These gaps in continuation and disparities in attainment have not translated into universal support from universities and colleges. In their access and participation plans submitted to the OfS as of March 2020, only 40 out of 230 included targets related to mature students. Of these, 27 were from universities, the rest from colleges or specialist providers. 37 had written commitments, such as bursaries and student support, and the majority of these related wholly or in part to access.

There is a need for greater choice of how to study, more flexible course structure and improved transitional support, particularly in the first year of higher education, or through foundation years and access courses.60 This support could include changes to the course structure, modular provision, evening seminars and childcare.

As we emerge from the pandemic, there will be more need than ever for opportunities to be available to mature students to reskill and upskill. Local opportunities for study and different pathways may be increasingly important, including higher education and further education partnerships, technical qualifications, and Access to Higher Education qualifications. Over the coming year, we will engage with universities and colleges to build these routes more substantially into access and participation plans.

New opportunities for mature students

There are signs that a corner has been turned. Even before the pandemic, part-time entrant numbers to the Open University had stopped falling.61 During the pandemic, long-standing providers of remote higher education have reported an increase in enrolments.62 UCAS has released figures that show mature applicants from the UK rising by 24 per cent to 96,390. Applications for nursing from students aged 35 and over saw an increase of 39 per cent.63 Nor is it evident that mature students who complete their studies are having a worse experience than their younger counterparts.

Case study: Deakin University, Australia: A welcoming environment for cloud learners

Deakin University has over 60,000 students, with around 45,000 returning to study after a prior tertiary course, career or family break. About 30 per cent of all students choose to study online in cloud courses. These are overwhelmingly (circa 95 per cent) returning to study, and their experience is a useful lens on effective adult learning.

Deakin created its Cloud Campus, a virtual environment for students enrolled in online courses, to focus attention on the online student experience. To understand these students better, the university reviewed cohort characteristics and ran user experience studies.64 Cloud students are more likely to be older (75 per cent are over 24 years old), study part-time (70 per cent) and have families (48 per cent), and are evenly split between undergraduate and postgraduate study. Reconstruction of the student journey through longitudinal self-report identified key ‘pain points’ and interventions that could improve learning and experience. Cloud students wanted timely and consistent information, flexible services accessible online and asynchronously, and proactive engagement from staff who understood their perspective.

Deakin addresses identified issues by embedding the cloud student perspective in quality assurance and uplift of processes and tools. Student feedback, success and outcomes are reported for cloud students alongside reports for physical campuses. Cloud student representatives are included in university committees and in major project consultation. Cloud Campus experts work alongside operational teams to identify and resolve pain points.

Deakin’s online learning was developed from decades of distance education and early adoption of digital educational technologies. It has succeeded thanks a university-wide commitment to call out the experience and needs of learners looking for flexible ways to study.

Online offerings such as massive open online courses have long been proposed as a solution to some of the barriers mature students face, allowing them to pick and choose modules from a wide variety of providers and complete them at their own pace. While take-up has been high, however, completion rates are often below 10 per cent.65

Online teaching and learning have been catalysed by the pandemic as seminars and lectures have needed to be delivered remotely. If this trend continues, it could benefit mature students who want to study remotely or flexibly around work or caring commitments. It will be important, though, to consider the barriers that students face when accessing this provision. Access to the internet varies by region: 38 per cent of students in the North West had experienced a lack of reliable internet access, compared with just 23 per cent in London.66 Such regional inequalities will have to be addressed if digital learning is to be available to all.

What the OfS is doing to drive change

As this brief has detailed, the choice open to mature students has been narrowing. The OfS is working to facilitate more choice, opportunity and flexibility across the sector. Through the access and participation plans, we require providers to consider how they support mature students throughout the student lifecycle, and set out how they intend to address gaps in performance where they find them. Although mature students have not been prioritised by many providers to date, we expect more focus to be given to them as we agree changes to plans following the pandemic.

We have been developing our outreach and access initiatives to target mature students. Online information, advice and guidance resources such as Discover Uni offer practical advice and support tailored towards prospective mature students.67 We will increase the focus of Uni Connect partnerships on working with employers and communities to support mature student participation, including a stronger role for further education colleges, and progression from further to higher education.68

In addition to our work to support local graduates, we are funding 18 universities to develop postgraduate conversion courses to allow people with degrees outside the areas of science, technology, engineering and maths to retrain in artificial intelligence. The programme is expected to create at least 2,500 postgraduates. A key aim of this initiative is to increase diversity and the number of people from underrepresented backgrounds in the fields of artificial intelligence and data.

We have seen a notable rise in mature students accepted onto nursing courses and we will continue to work with Health Education England to support government plans to increase opportunities for nursing, building on the research, advice and guidance we have published in this area.69

Conclusion

Over the last 15 years, there has been a gradual narrowing of options and opportunities for mature students. Part-time study – especially under 50 per cent intensity – has been hollowed out. Digital and online courses have yet to fill the gap. For those who cannot study full-time because of other commitments, this lack of part-time provision means that higher education is not a viable option. Rectifying these issues will require involvement from the government, universities and colleges, and the OfS.

There are encouraging signs that mature students may be returning in greater numbers to higher education. Mature applicants have risen, especially in nursing. The introduction of remote learning, necessitated by the pandemic, has offered more flexible provision to those with other responsibilities.

The government’s proposals for the Lifelong Loan Entitlement and more flexible provision could encourage this nascent regrowth. Universities and colleges can build on the remote teaching and learning they introduced in the pandemic. The OfS will continue to fund and evaluate projects to create opportunities for mature students, to improve the information, advice and guidance available to them and to give them greater prominence in our access and participation work.

It is imperative that the momentum that is building for mature students is not lost after the pandemic. Improved choice, funding and flexibility will be essential to set mature and younger students on a truly equal footing.

Please note: Under the heading ‘Background’ on page 2 of the Insight brief, a correction was issued on Friday 4 May 2021 as follows.

The paragraph previously read: ‘In 2019-20 there were 705,000 mature students studying at undergraduate level at English higher education providers (45.6 per cent of the total number of undergraduates). Almost all postgraduate students are mature – 527,000 or 99.3 per cent of the total in 2019-20.’

The reference for this statement was https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/sb258/figure-5. The statistics in this statement are based on selecting country of provider as England, and level of study ‘All undergraduate’, then summing the number of students in the age group categories 21-25 and above. However, since the Higher Education Statistics Agency uses age at the start of the academic year (https://www.hesa.ac.uk/collection/c19051/derived/xagrp601), this definition of mature is different from our own, which only includes those who are 21 and over on entry to their course. This makes a material difference to the number and proportion of mature students.

Following the correction, we now use data from our equality and diversity webpages.

Note: This page and PDF download were updated on 10 May 2022 to correct references to the Lifelong Loan Entitlement.

1 In this brief, for the sake of readability, we have used ‘universities and colleges’, or sometimes simply ‘universities’, to refer to what our Regulatory framework and other more formal documents call ‘higher education providers’.

2 McCune, Velda, Jenny Hounsell, Hazel Christie, Viviene E Cree, and Lyn Tett, ‘Mature and younger students' reasons for making the transition from further education into higher education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 2010, pp691-702.

3 Centre for Transforming Access and Student Outcomes (TASO), ‘Analysis report: Supporting access and student success for mature learners’, April 2021 (available at https://taso.org.uk/news-item/universities-could-attract-more-mature-learners-by-offering-online-or-blended-learning/).

4 Datafile available to download alongside this brief at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/improving-opportunity-and-choice-for-mature-students/; Callender, Claire, and John Thomson, ‘The lost part-timers: The decline of part-time undergraduate higher education in England’, 2018 (available at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066734/), p20.

5 Learning and Work Institute, ‘Rates of adult participation in learning’ (https://learningandwork.org.uk/what-we-do/lifelong-learning/adult-participation-in-learning-survey/rates-of-adult-participation-in-learning/).

6 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, ‘Adult education level’ (https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/adult-education-level.htm). These statistics define upper secondary education as ‘the final stage of secondary education’ (https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=5450).

7 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, ‘Enrolment rates of the population aged 25 years or older, by level of education (2018)’ (https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/enrolment-rates-of-the-population-aged-25-years-or-older-by-level-of-education-2018_69b79b87-en).

8 Prospects, ‘Skills shortages in the UK, 2019/20’, December 2019 (available at https://luminate.prospects.ac.uk/skills-shortages-in-the-uk).

9 Office for National Statistics, ‘Labour market overview, UK: May 2021’, (https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/may2021).

10 Ford, Megan, ‘Nursing courses see 32% rise in applications during COVID-19’, Nursing Times, 18 February 2021 (https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/education/nursing-courses-see-32-rise-in-applications-during-covid-19-18-02-2021/).

11 Houston, Donald, ‘The unevenness in the local economic impact of COVID-19 presents a serious challenge to the government’s “levelling up” agenda’, November 2020 (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/local-economic-impact-covid19/); Office for National Statistics, ‘Labour market in the regions of the UK: May 2021’ (https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/regionallabourmarket/may2021); Institute for Fiscal Studies, ‘Levelling up: Where and how?’, October 2020 (available at https://ifs.org.uk/books/levelling-where-and-how).

12 OfS, ‘Gravity assist: Propelling higher education towards a brighter future’, March 2021 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/gravity-assist-propelling-higher-education-towards-a-brighter-future/).

13 Department for Education, ‘Skills for jobs: lifelong learning for opportunity and growth’, January 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/skills-for-jobs-lifelong-learning-for-opportunity-and-growth).

14 OfS, ‘Equality and diversity student data’, www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/equality-and-diversity-student-data/equality-and-diversity-data/

15 Million Plus and National Union of Students, ‘Never too late to learn: Mature students in higher education’, May 2012 (available at https://www.millionplus.ac.uk/policy/reports/never-too-late-to-learn), pp7-8; Sutton, Charlotte E, ‘Does age matter in higher education? Investigating mature undergraduate students’ experiences’, PhD Thesis, 2019 (available at https://leicester.figshare.com/articles/thesis/Does_Age_Matter_in_Higher_Education_Investigating_Mature_Undergraduate_Students_Experiences/10321283), pp71-76.

16 UCAS, ‘Admissions patterns for mature applicants’, August 2018 (available at https://www.ucas.com/file/175936/downl), pp13-14.

17 Weinbren, Daniel, The Open University: A history (2015); Parry, Gareth, and Anne Thompson, ‘Closer by Degrees: The past, present and future of higher education in further education colleges’, 2002 (available at https://dera.ioe.ac.uk//10140/); Fielden, John and Robin Middlehurst, ‘Alternative providers of higher education: Issues for policymakers’, January 2017 (available at https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2017/01/05/3762/), p29.

18 William Whyte, ‘Somewhere to live: Why British students study away from home – and why it matters’, November 2019 (available at https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2019/11/14/somewhere-to-live-why-british-students-study-away-from-home-and-why-it-matters/).

19 Holton, Mark, and Kirsty Finn, ‘Being-in-motion: The everyday (gendered and classed) embodied mobilities for UK university students who commute’, Mobilities, 2018, pp426-40; Holton, Mark, ‘Traditional or non-traditional students? Incorporating UK students’ living arrangements into decisions about going to university’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 2018, pp556-569; Pokorny, H, D Holley and S Kane, ‘Commuting, transitions and belonging: The experiences of students living at home in their first year at university’, Higher Education, 2017, pp543–58.

20 OfS, ‘National Student Survey – NSS: Sector analysis’, (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/sector-analysis/).

21 These other characteristics are sex, ethnicity, mode of study, subject of study, disability status. This gap could be related to a large proportion of mature students learning through long-distance methods or being clustered at a small number of providers.

22 TASO, ‘Summary report: Supporting access and student success for mature learners’, April 2021 (available at https://taso.org.uk/news-item/universities-could-attract-more-mature-learners-by-offering-online-or-blended-learning/), p4.

23 CFE Research, ‘Data use for access and participation in higher education’, February 2020 (available at

www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/data-use-for-access-and-participation/), p52.

24 Datafile available to download alongside this brief at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/improving-opportunity-and-choice-for-mature-students/.

25 Available to download alongside this brief at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/improving-opportunity-and-choice-for-mature-students/.

26 Swain, Jon, and Cathie Hammond, ‘The motivations and outcomes of studying for part-time mature students in higher education’, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 2011, pp591-612; McCune, Velda, Jenny Hounsell, Hazel Christie, Viviene E Cree and Lyn Tett, ‘Mature and younger students' reasons for making the transition from further education into higher education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 2010, pp691-702; Busher, Hugh and Nalita James ‘Mature students’ socioeconomic backgrounds and their choices of Access to Higher Education courses’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 2020, p641; TASO, ‘Analysis report: Supporting access and student success for mature learners’, April 2021 (available at https://taso.org.uk/news-item/universities-could-attract-more-mature-learners-by-offering-online-or-blended-learning/).

27 Butcher, John, and John Rose-Adams, ‘Part-time learners in open and distance learning: revisiting the critical importance of choice, flexibility and employability’, Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 2015, pp127-37; Bridgstock, R, 2009, ‘The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills’, Higher Education Research and Development, 2009, pp31-44.

28 OfS, ‘Analysis of Level 6 and 7 apprenticeships’, May 2020 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/analysis-of-level-6-and-7-apprenticeships/), p4.

29 OfS, ‘Consistency needed: Care experienced students and higher education’, April 2021 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/consistency-needed-care-experienced-students-and-higher-education/#Background).

30 Farley, Helen, and Anne Pike, ‘Engaging prisoners in education: Reducing risk and recidivism’, Advancing Corrections: Journal of the International Corrections and Prisons Association, 2016, pp65–73.

31 Refugee Support Network, ‘“I just want to study”: Access to higher education for young refugees and asylum seekers’, February 2012 (available at https://www.reuk.org/resources/13-i-just-want-to-study-access-to-higher-education-for-young-refugees-and-asylum-seekers), pp7-9.

32 ‘Number of UK-domiciled undergraduate students to English higher education providers 2006-07 to 2019-20’, May 2021 (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/official-statistics/published-statistics/).

33Available to download alongside this brief at https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/improving-opportunity-and-choice-for-mature-students/. Note that this analysis is restricted to courses leading to a qualification, which aligns with data we publish on access and participation but means a significant number of mature students will not be in the scope of this analysis. For an indication of the decrease in mature students studying on courses for institutional credit rather than a qualification see Callender, Claire, and John Thomson, ‘The lost part-timers: The decline of part-time undergraduate higher education in England’, 2018 (available at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066734/), p20, Figure 4. There is also some higher education provision before 2014-15 not reported, because providers that now submit to the Higher Education Statistics Agency Student Alternative return were not required to report data until that year.

34 House of Commons Library, ‘Higher education student numbers’, February 2021 (available at https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7857/), p26.

35 House of Commons Library, ‘Mature students in England’, February 2021 (available at https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8809/), p21.

36 Callender, Claire, and John Thomson, ‘The lost part-timers: The decline of part-time undergraduate higher education in England’, 2018 (available at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066734/), pp24-25.

37 The Open University, ‘Fixing the broken market in part-time study’, November 2017 (available at https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2017/11/16/time-tackle-part-time-crisis/), p8.

38 Callender, Claire, ‘The 2012-13 reforms of student finances and funding in England: The implications for the part-time undergraduate higher education sector’ in Brada, JC, W Bienkowski and M Kuboniwa (eds) International Perspectives on Financing Higher Education, 2015, pp80-97

https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/42796/1/published%20Poland%20PT%20students%2018-06-2014%202.pdf [PDF], pp9-10.

39 Department for Education, ‘Post-18 choice of part-time study’, May 2019 (available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/post-18-choice-of-part-time-study), p49.

40 Callender, Claire, ‘Putting part-time students at the heart of the system?’, Higher Education Policy Institute, 2015 (available at https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2015/10/29/finance-stupid-decline-part-time-higher-education/), p21.

41 Universities UK, ‘UUK Review of part‐time and mature higher education: Survey of stakeholder evidence’, October 2013 (available at https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/26225/1/PowerOfPartTime.pdf), p6.

42 Butcher, John, ‘“Shoe-horned and side-lined”? Challenges for part-time learners in the new HE landscape’, July 2015 (available at https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/shoe-horned-and-side-lined-challenges-part-time-learners-new-he-landscape)

), pp21, 26-27.

43 Callender, Claire, ‘Putting part-time students at the heart of the system?’, Higher Education Policy Institute, 2015 (available at https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2015/10/29/finance-stupid-decline-part-time-higher-education/), pp21-22, 31.

44 Learning and Work Institute, ‘Rates of adult participation in learning’ (https://learningandwork.org.uk/what-we-do/lifelong-learning/adult-participation-in-learning-survey/rates-of-adult-participation-in-learning/).

45 Oxford Economics, ‘Macroeconomic influences on the demand for part-time higher education in the UK’, April 2014 (available at https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A62328, p14.

46 Department for Education, ‘Skills for jobs: Lifelong learning for opportunity and growth’, January 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/skills-for-jobs-lifelong-learning-for-opportunity-and-growth).

47 UCAS, ‘Admissions patterns for mature applicants’, August 2018 (available at https://www.ucas.com/file/175936/downl), p15.

48 OfS, ‘Maps showing the distribution of higher education places in England, 2017-18’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/annual-review-2019/a-new-approach-to-fair-access-participation-and-success/#beforeofs).

49 Providers are categorised according to their tariff group, using the same methodology as in our key performance measure 2 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/measures-of-our-success/participation-performance-measures/gap-in-participation-at-higher-tariff-providers-between-the-most-and-least-represented-groups/). Higher tariff providers are the top third of English higher education providers when ranked by average tariff score of UK domiciled undergraduate entrants. Tariff scores are defined using Higher Education Statistics Agency data from academic years 2012-13 to 2014-15.

50 Henderson, Holly, ‘Place and student subjectivities in higher education “cold spots”’, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2019, pp331-45.

51 Available to download alongside this brief at https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/improving-opportunity-and-choice-for-mature-students/

52 OfS, ‘Access and participation data dashboard’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/).

53 Lavender, Kate, Mature students’ experiences of undertaking higher education in English vocational institutions: Employability and academic capital’, International Journal of Training Research (2021).

54 Prospects, ‘What do graduates do? Regional edition’, October 2019 (available at https://luminate.prospects.ac.uk/what-do-graduates-do-regional-edition), p32.

55 OfS. ‘Improving outcomes for local graduates’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/skills-and-employment/improving-outcomes-for-local-graduates/).

56 OfS, ‘Access and participation data dashboard’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/).

57 As a result of the pandemic, a number of providers made changes to assessment and classification arrangements to ensure students were not disadvantaged by the impact of COVID-19 when it came to assessment in 2019-20. Providers did not adopt a single approach, and as a result, the impact of these changes will have varied from provider to provider. It is not possible to determine the extent to which these actions by providers may have influenced the increase in attainment rates seen between 2018-19 and 2019-20.

58 OfS, ‘Access and participation data dashboard’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/).

59 OfS, ‘Access and participation data dashboard’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/).

60 Farmer, Julie, ‘Mature access: The contribution of the Access to Higher Education diploma’, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 2017, pp63-72.

61 OfS, ‘Access and participation data dashboard’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/).

62 Busby, Eleanor, Evening Standard, ‘More people sign up for Open University online courses amid pandemic’, 6 May 2021 (https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/open-university-england-students-kent-government-b933492.html).

63 UCAS, ‘Nursing applications soar’, February 2021 (https://www.ucas.com/corporate/news-and-key-documents/news/nursing-applications-soar-ucas-publishes-latest-undergraduate-applicant-analysis).

64 O’Donnell, M, and L Schulz, 2020, ‘Learning design meets service design for innovation in online learning at scale’, in McKenzie, S, M Mundy, F Garivaldis and K Dyer (eds), The Tertiary Online Teaching and Learning (TOTAL) Guide.

65 Gütl, C, RH Rizzardini, V Chang, and M Morales, ‘Attrition in MOOC: Lessons learned from drop-out students’ in Uden, L, J Sinclair, YH Tao and D Liberona (eds), Learning Technology for Education in Cloud: MOOC and Big Data, 2014, pp37-48.

66 OfS, ‘Gravity assist: Propelling higher education towards a brighter future’, March 2021 (available at www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/gravity-assist-propelling-higher-education-towards-a-brighter-future/), p65.

67 Discover Uni, ‘Over 21 and starting uni?’ (https://discoveruni.gov.uk/over-21-and-starting-uni/).

68 OfS, 'Supporting adult learners' (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/skills-and-employment/supporting-adult-learners/).

69 OfS, ‘Health education funding’ (www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/funding-for-providers/health-education-funding/strategic-interventions-in-health-education-disciplines/).

Last updated 28 May 2021 + show all updates

28 May 2021 - Correction made to note 14

Describe your experience of using this website